MASTERS THESIS: Things, by Elisa Werbler

We live in a world of things. Thousands of things surround us everyday, but we interact with only a fraction of them on a regular basis. Some of these things are functional, and help us to complete our daily tasks. Some of them act only as a physical reminder of a certain place and time. These things are inanimate and unable to express emotion, and yet, they have a powerful ability to recount stories, create interactions, and even build identities.

Elisa Werbler’s master's thesis, titled Things, explores how we ascribe value to our everyday possessions. It examines the things we cherish from our pasts, the things that signify our relationships with others, the things we consume, the things we share, and the things we can’t bear to part with. What started with a fascination in how humans attribute meaning and assign value to inanimate objects, evolved into the realization that the ability to do so contributes to the fact that “We simply have too many things,” says Elisa.

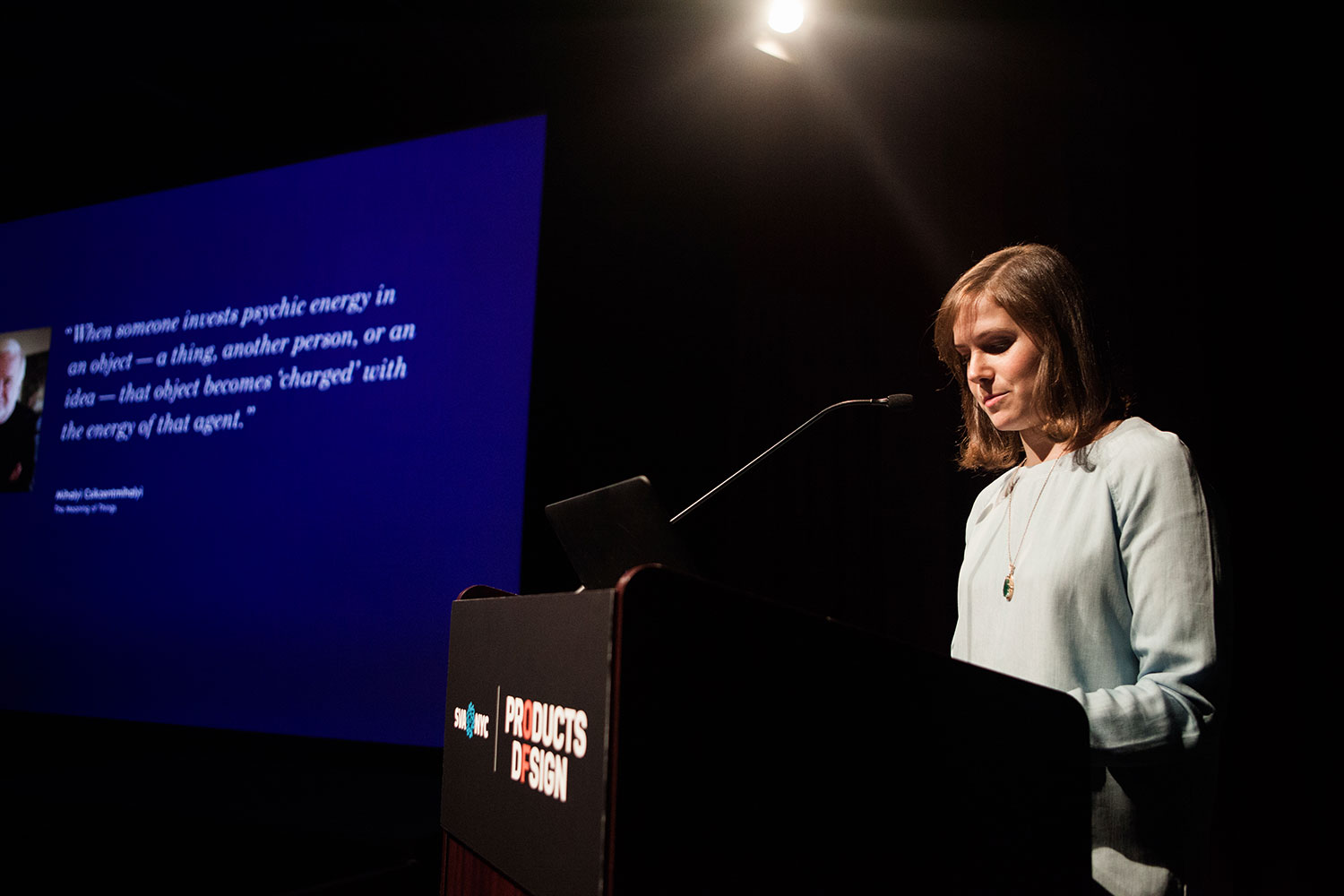

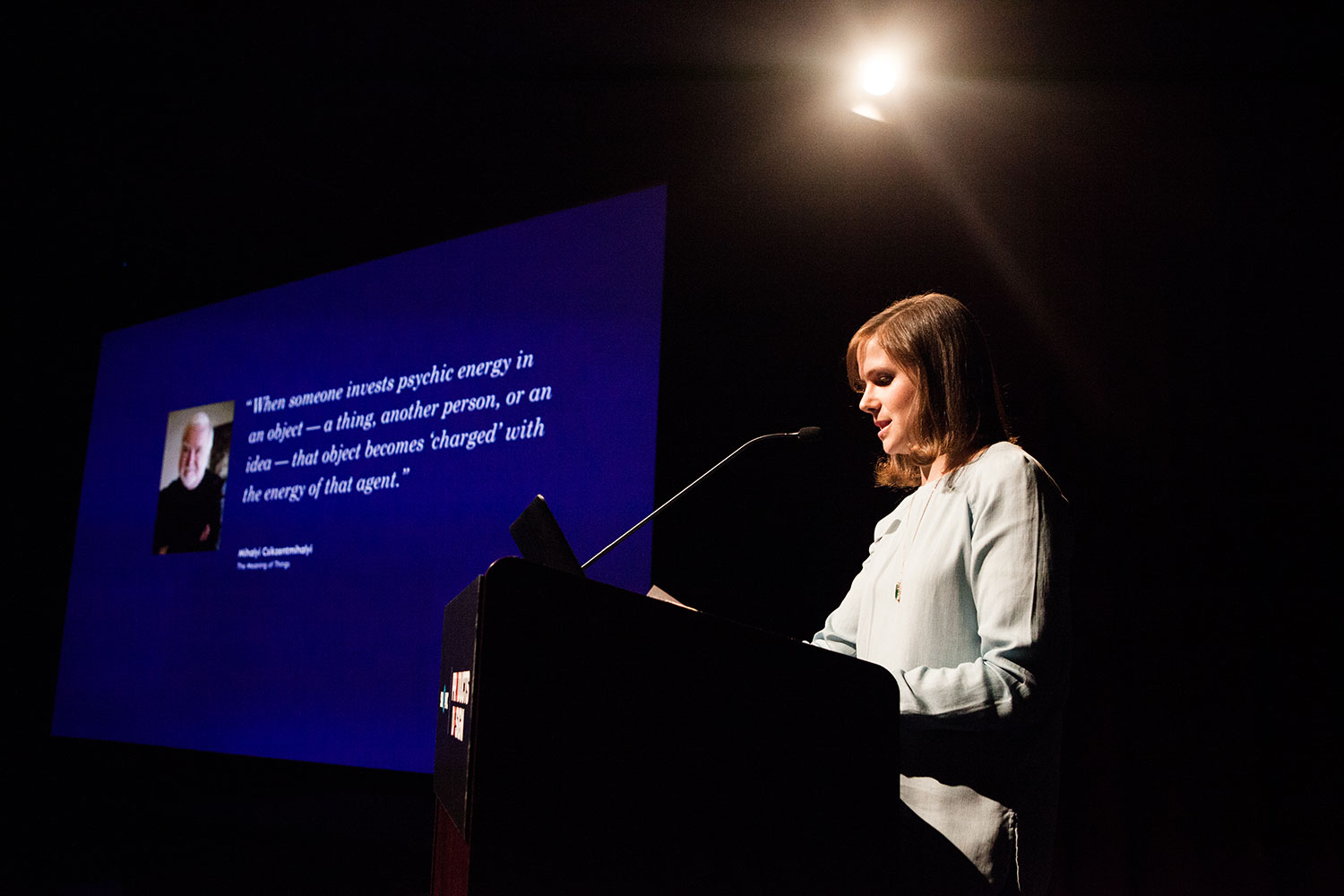

Watch Elisa Werbler's live thesis presentation and Q&A below:

Western society suffers from an affliction known as “loss-aversion,” which means that the pain of losing something is greater than the pleasure of gaining something. This term, coined by world renowned psychologist Daniel Kahneman, goes hand in hand with what’s known as “the endowment effect”—the idea that something is more valuable to you than to anyone else, simply because it’s yours. The combination of these two ideas led Elisa down a path of trying to pinpoint the exact moment when a decision is being made about something—whether it is in anticipation of a purchase, or an attempt to let something go.

Western society suffers from an affliction known as “loss-aversion,” which means that the pain of losing something is greater than the pleasure of gaining something.

Elisa felt the urgency of using design as a means to tackle this problem. One month into the start of her thesis, A New York Times best-selling book came out in the United States and reinforced the magnitude of the proglem (and the size of her potential audience). Soon, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up by professional organizer Marie Kondo became an instant sensation across the globe. Kondo challenges her readers to ask each and every object the question “Does this spark joy?” as a metric to determine whether or not it is worthy of keeping, and emphasizes the idea that it is about deciding what to keep, not what to let go of.

Elisa's research included everything from understanding the psychology behind why we create attachments to things, to case studies about individuals who have decreased their amount of personal possessions "to under 100 things." She conducted interviews with subject matter experts such as Rob Walker, co-author of the book Significant Objects, Gail Steketee, Dean and Professor at the Boston University School of Social Work and co-author of the book Stuff: Compulsive Hoarding and the Meaning of Things, and Amelia Meena, professional organizer and founder of Appleshine Lifestyle Organization.

"It is easier to let go of something if you don’t remember that it’s there."

The goal of the thesis aimed to create a culture of mindfulness with regard to material things, and was guided by two principles that Elisa uncovered through her research: The first is that we need to become more in-tune with the things we already have; in doing so, we can better filter what we allow to enter into our lives in the future. The second is that it is easier to let go of something if you don’t remember that it’s there.

Decision Dice and Lossless

Early on, she created a set of Decision Dice, which pairs both a question and an answer together that one might not think of on their own. This challenges the user to think about their things in a new light. "You can replace it? Toss it."

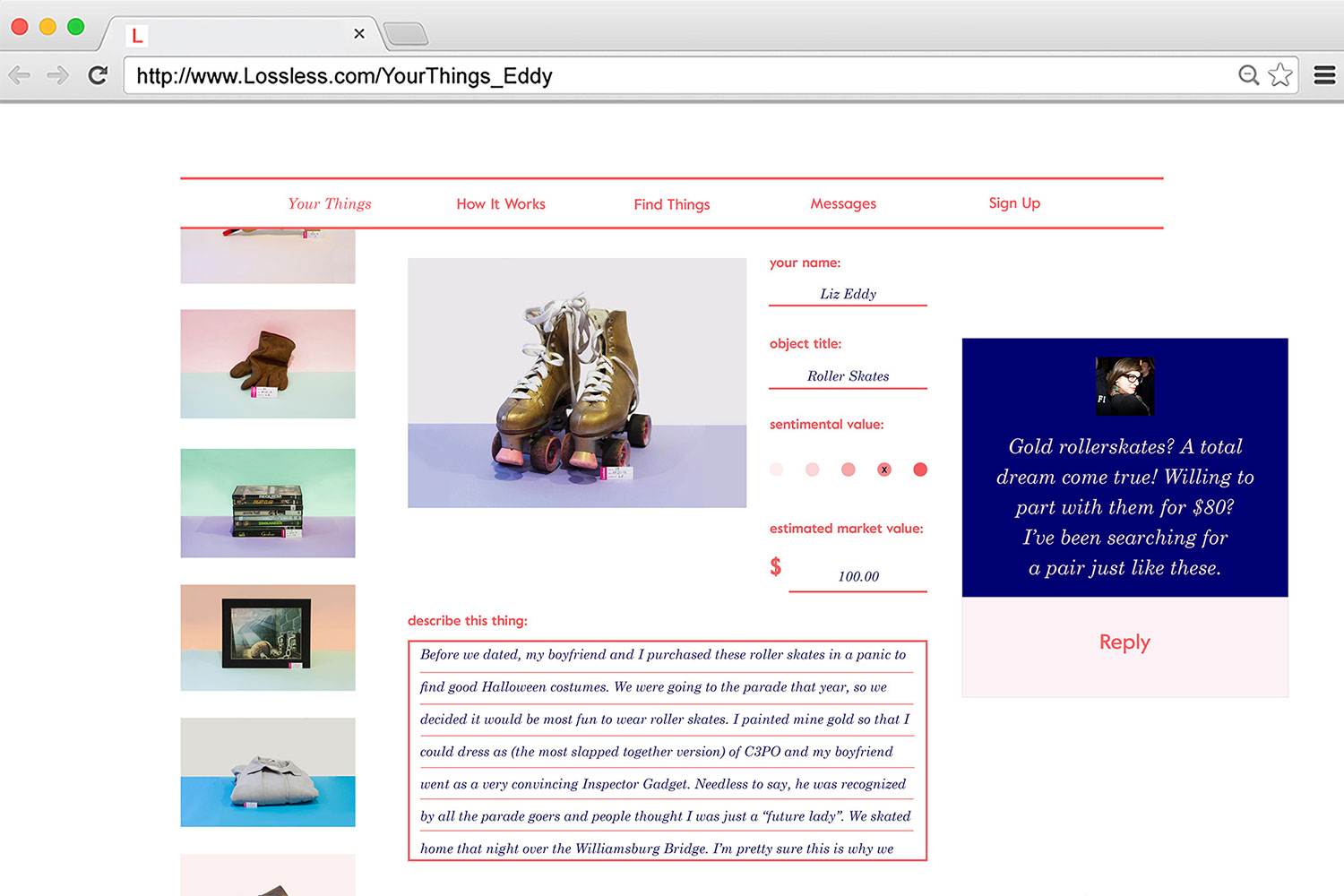

Next, Elisa developed a service called Lossless, which deals with proximity in relation to one’s belongings. The term “lossless” is a digital term referring to the ability to compress files, documents, images or video to a smaller size without losing quality. The service aims to help people get rid of the things that are weighing them down, so that they can enjoy the things that aren’t. Lossless gives users the tools to help identify the things that they do not feel are essential, but are having a hard time letting go of. Those things are catalogued and added to the user's personal digital archive, which they can access at any time. The items are then removed from the home and placed into storage. The catalogue is then used as an individual listing for each item that others can view and bid on. The user is then faced with the decision to either sell the item, or have it returned to their home.

Elisa wanted to test the efficacy of this service and viability as an actual business, so using design-led research, she prototyped the process by going into someone’s home "and giving it the Lossless treatment."

Trappings

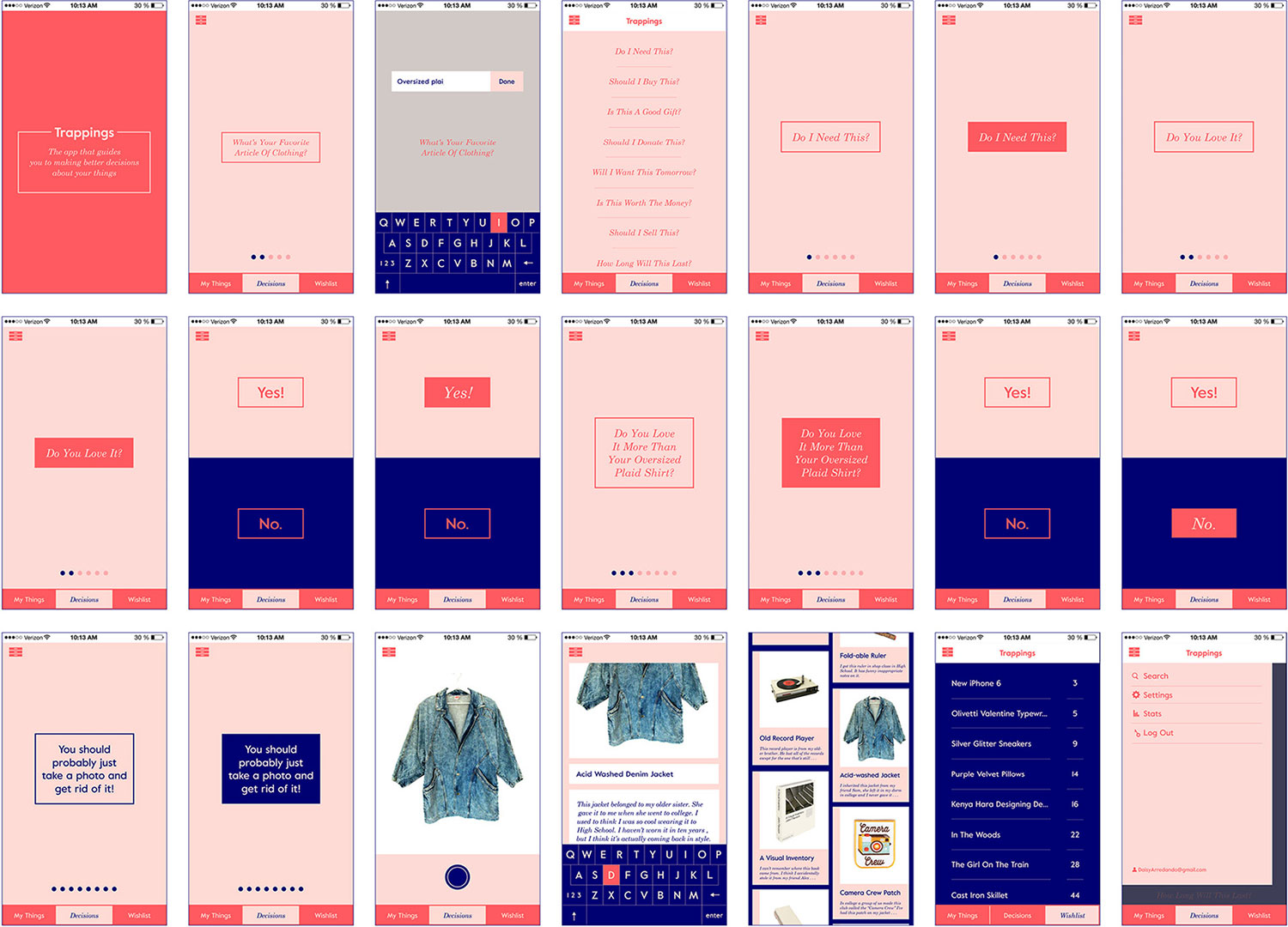

The learnings from the Lossless prototype led Elisa to create Trappings, which is designed to battle the internal dialogue that goes on inside our minds as we contemplate the status of our things. Trappings is there for you in times of need, like moments you are considering a new purchase. The goal is to create positive behaviors around your things by being more contemplative, rather than making mindless decisions. Elisa was also inspired by her conversation with professional organizer Amelia Meena, who said in reference to people letting go of things, “Sometimes people just need permission, or a good push.”

Trappings is designed to battle the internal dialogue that goes on inside our minds as we contemplate the status of our things.

Trappings is a mobile application that acts like an interactive flow chart. It starts by asking you targeted questions about your things, such as “What is your favorite article of clothing?” or “What is your most prized possession?” These answers are then used as a way to elicit an emotional response. The user goes through an additional series of targeted questions for each unique item that they are having a hard time making a decision about, and the application helps them get to a response. For example, you could start by clicking on the question “Should I Buy This?” when confronted with a new purchase.

Users can also create a wish list in the app. It keeps track of how long each item has been on your wish list and periodically asks you if you still want it there. Trappings tracks your responses, and gives feedback on your answers. By visualizing your journey through each set of questions, the user can begin to gain insights into their behaviors and shift them accordingly. Much like Lossless, you can digitize those items you are ready to part with.

Chain-Of-Custody? Think of it as a 'living will' for your things.

Chain-Of-Custody

Lastly, Elisa created Chain-Of-Custody—a way to preserve your most valuable objects, and to communicate to your loved ones which things are most important to you and what you would like to be passed on. Think of it as a living will for your things. It consists of a series of bags, ranging from the very small (something you might put jewelry in) to the quite large (large enough for furniture to fit in). Each bag has a label on it to indicate when and where it should go. A valve at the bottom is used to remove any remaining air once the bag has been sealed.

The purpose of Chain-Of-Custody is to put a physical layer between you and your things. It’s an opportunity to question the value of your things while you’re still here, so that the burden of doing so is not left to the ones you love...when you’re not.

Elisa has already seen the effects of this thesis work on her own life, but is most excited to see the effects on those around her; it has already proven to be contagious.

Learn more about Elisa Werbler's work at elisawerbler.com and contact her at elisa[at]elisawerbler[dot]com.