Design & Politics: The 2018 Midterm Elections

“Design is intrinsic to politics,” argue faculty Jennifer Rittner, Marc Dones, and Andrew Schlessinger. “In fact, the entire Democratic experiment is a product of design.”

In the Products of Design program, an opportunity to investigate the direct relationship between design and politics occurs biennially with the U.S. elections. This year, it was all about the Midterm Elections—when politicians compete for seats in the U.S. Legislative branch (Congress), as well as in State and Local political races.

The opportunity space for the 3-day workshop was Messaging. In a tense political climate, mixed groups of first- and second-year PoD teams investigated how design can mitigate the negative impacts of political messaging, and develop design strategies that fully enfranchise citizens in the democratic process. They then took their work out into the streets of New York City.

Students investigated how design can mitigate the negative impacts of political messaging, and develop design strategies that fully enfranchise citizens in the democratic process.

Assessing tone, visual language, verbal language and sound design, they revealed the ways in which political messaging incites emotional responses (provocation “LEMON-AID”); communicates our collective values (provocation “I SEE A LEADER”); and serves to increase or depress voter turnout (provocation “ACTION OR APATHY”).

They investigated the degree to which political messaging is aligned with or divorced from policy, action, and governance (provocation “I BELIEVE”); and developed response mechanisms for addressing tactical concerns like voter identification (provocation “I DO ID”); and non-citizen participation in political engagement (provocation “VOICE”).

“The next opportunity on the horizon is to turn these insightful investigations into design solutions for the 2020 elections,” offers the team. “The countdown begins; partnerships are welcomed!”

Provocation: “I DO ID”

Initiating Question: “What aspect of your identity motivate you to the political action?”

Team: Qixuan Wang, Victoria Ayo, Pantea Parsa, Zihan Cheng, Andre Orta, Stephanie Gamble

Location: Grand Central Station

Provocation “I DO ID” investigates how far citizens would be willing to go to establish their identity as voters. Participants were invited to consider and vote on options from among four categories: Social Trust, Personal Data, Policy and Physical Alteration. From familiar forms of printed ID cards to more radical options such as fingerprint, DNA sample or microchip, participants were asked consider what privacy and identity mean to them in the context of voter suppression, voter fraud and citizen rights.

“I DO ID” emerged from an initial examination of the complex faucets of identity in the political sphere. How does identity affect voting behavior? What part of one’s identity motivates one to vote? How is identity classified by political systems? While identity is complicated, nuanced and encompasses, identification itself is tactical.

A simply-designed poster provided the bridge for entering into conversations with participants without imposing the group’s personal biases. On a rainy Election Day, people in Grand Central Station paused, considered, interacted and offered their insights. A surprising finding: a majority of participants would be willing to give up their privacy—just short of inserting a microchip—in order to prove their identity.

As one participant stood in front of the board for several minutes with a conflicted look on her face, PoD student Stephanie Gamble prompted her, “Would you share what you are thinking about right now?” She replied “I’m just thinking about how I would have answered this differently years ago, when I was younger. Things these days have me thinking twice.”

“I DO ID” had provoked her to grapple with the question of identity. The next opportunity for designers is to develop a set of affirmative design artifacts n time for the 2020 elections.

Provocation: “I SEE A LEADER”

Initiating Question: “How might we reveal how people internalize ideas about gender and leadership?”

Team: Ben Bartlett, Yuko Kanai, Shin Young Park, Ted Scoufis, Hannah Rudin, Antya Weagemann

Location: Chelsea Market

How do the mental models we construct based on media representations of leaders inform the choices we make about voting? Team “I See a Leader” explored this question, focusing initially on gender.

Chelsea Market, which attracts tourists from many parts of the world, offered an ideal setting for the team to hear a broad range of ideas. They set up sketch artist stands there, each with an illustrator and an interviewer who would work with participants to visualize their ideal leader. The interviewer asked each participant to describe their ideal leader’s physical attributes, prompting them as needed for more details, while taking care not to prime their responses to conform to an expectation.

This co-authoring, co-creation pop-up revealed radical ideas about the attributes of leadership and set the stage for some provocative, nuanced conversations about the representation of leadership in popular media. The sketching exercise allowed participants to externalize these ideas, sharing them not only with the research team but also we spectators in the public space who could respond or reflect on this provocative images.

While participants did not show a strong preference for common physiological attributes, they did indicate their desire for someone who represents their identities through design – principally fashion or the design of their appearance. How, then, do we square these responses with the choices people make in the voting booth?

Provocation “I See A Leader” raises more questions about the incongruence between our fantasy leader sand the decisions we make at the ballot. How might our media landscape offer more radical representations of leadership? How can design influence the messages we receive about what constitutes the look of a leader?

If Provocation “I See A Leader” is any indication, we need more representation by leaders who aren’t afraid to dress down, sport multi-colored hair or wear prosthetics in the shape of tree branches.

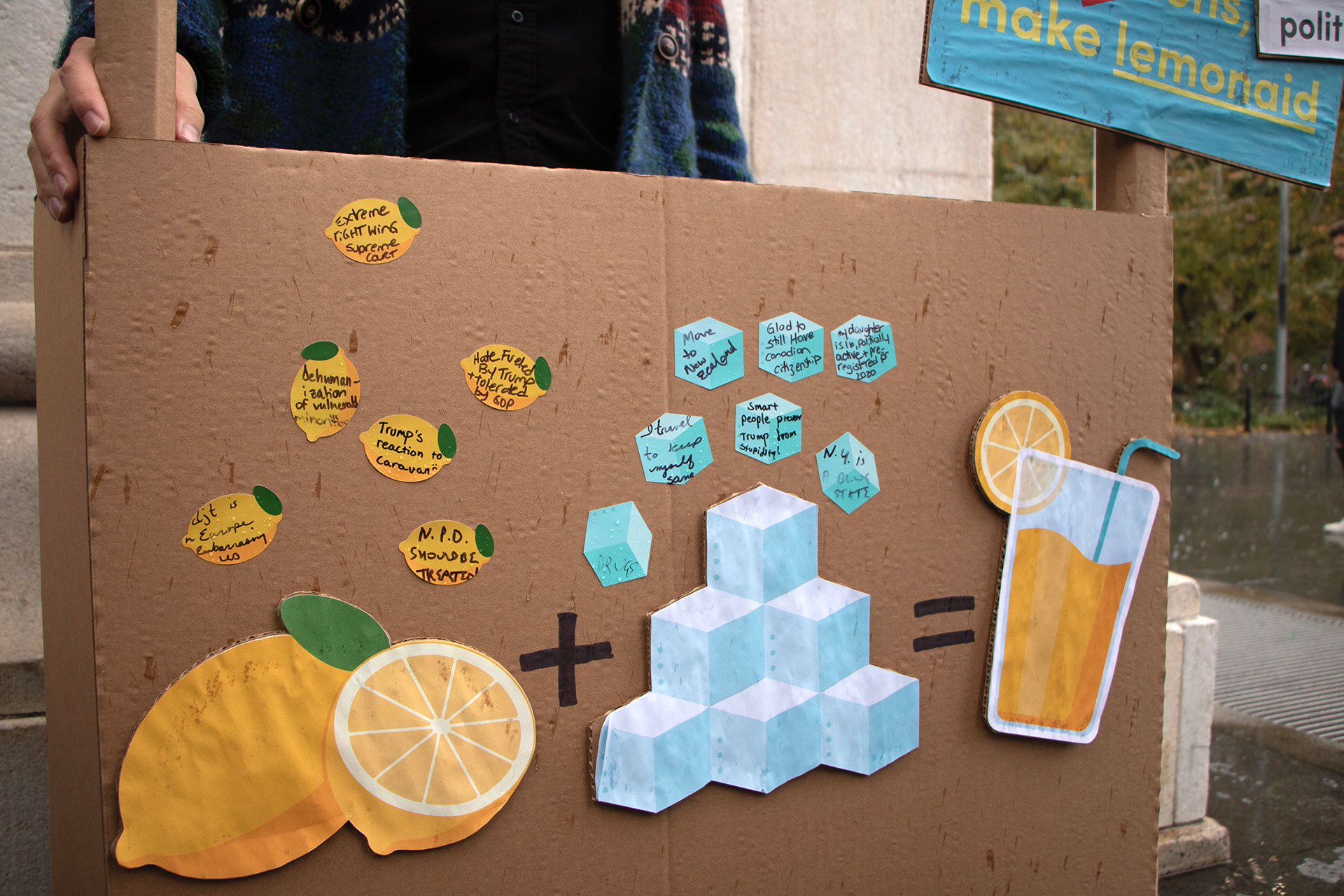

PROVOCATION “LEMON-AID”

Initiating Question: “Where is the line for freedom of speech? How might this differ for different people and across cultures? How might we bridge this difference?”

Team: Evie Chung, Wei Runshi, Gustav Gyrhauge, Hui Zheng, Sherry Wu, Bart Haney

Location: Washington Square Park

Therapists in the U.S. have coined a new term for the collective, politically-induced anxiety that seems to accompany our current political and media culture: “Trump Anxiety Disorder.” How might we create a space for people to unpack politically-induced anxiety and transform it into something constructive?

Introducing Provocation “Lemonaid,” a lemonade stand that leverages the nostalgia of childhood to induce positive thinking.

There is power in delight as a function. To that end, “Lemonaid” features a bright color palette of yellows and blues; iconography designed to be reminiscent of cartoons; and stickers to keep the engagement fun. In fact, the roughly-produced prototype offered a whimsical, low-barrier entry point for people to open up and talk about issues. By externalizing anxieties in a visually-playful, co-authored, interactive form, participants are invited to release them and consider, “how now can I turn these lemons into lemonade?”

On a rainy Friday afternoon just a few days after the mid-term elections, Team “Lemonaid” set up their stand in Washington Square Park. With a clear and concise script – using playful language associated with the making of lemonade – team members asked parkgoers to share: 1) a political anxiety on a lemon sticker and 2) an example of aid in the form of a sugar cube sticker. They were then invited to affix their stickers to the Lemonaid stand, where it could be off of their mind and shared, anonymously, with the world.

The intervention was intended to be entirely non-partisan and non-debate-centric. Lemonaid intended to discover the means by which we can relieve political anxiety, without seeking to change people’s politics. A further iteration might reveal additional steps for hearing, sharing and healing anxiety that may lead to positive steps in the real world, giving participants opportunities to engage with one another’s lemons and sugar cubes through collective action. By gathering more thoughts and opinions, perhaps there would be an opportunity to reduce anxiety and encourage more thoughtful, less polarized political conversation.

Provocation: “VOICE”

Initiating Question: “When people cannot vote, how do they exercise their political freedom? Political impact through non-voting actions.” Team: Carly Simmons, John Boran Jr., Yangying Ye, Felix Ho, Helen Chen, Yufei Wang

Location: Chinatown / Lower East Side

Given that 17% of New York City residents are not citizens, centering political conversations solely around voting is inherently exclusionary. Team “Voice” sought to reflect and empower non-citizen immigrants who voice their political opinions despite not being able to formally participate with a vote. Mirroring the NYC Votes branding, “I Voice” creates inclusion by offering wearable stickers that affirm, “I Voiced” in one of six languages: Traditional Chinese, Simplified Chinese, Korean, Hindi, Spanish, and English.

Traveling through the Lower East Side, Team “Voice” met with fourteen people from seven different countries: China, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Korea, USA, India, and Iran.

The two-day design intervention revealed widespread concern about anti-immigration policies and sentiments in the United States among voting and non-voting immigrants. Non-voters reported finding solace in their ability to organize around these issues within their communities; and many actively encourage friends and family who can vote to participate in the process and influence change.

Participants in the design provocation who “Voiced” but did not vote, received a sticker as a way to honor their actions; which many said made them feel included and empowered in a system that otherwise excludes them politically.

The artifact is the message, indicating that despite being dis-enfranchised from the political system they are still engaged in the collective endeavor of our democracy. The object serves as a form of recognition for the citizen while also reminding citizens around them, including politicians and the politically-minded, that non-citizen immigrants participate in the U.S. political system, even without the right to vote.

To Voice is to be heard; to wear the “I Voiced” sticker is to be seen. This artifact, more broadly adopted, offers an opportunity for non-voters to be more visible in a way that initiates positive policy changes.

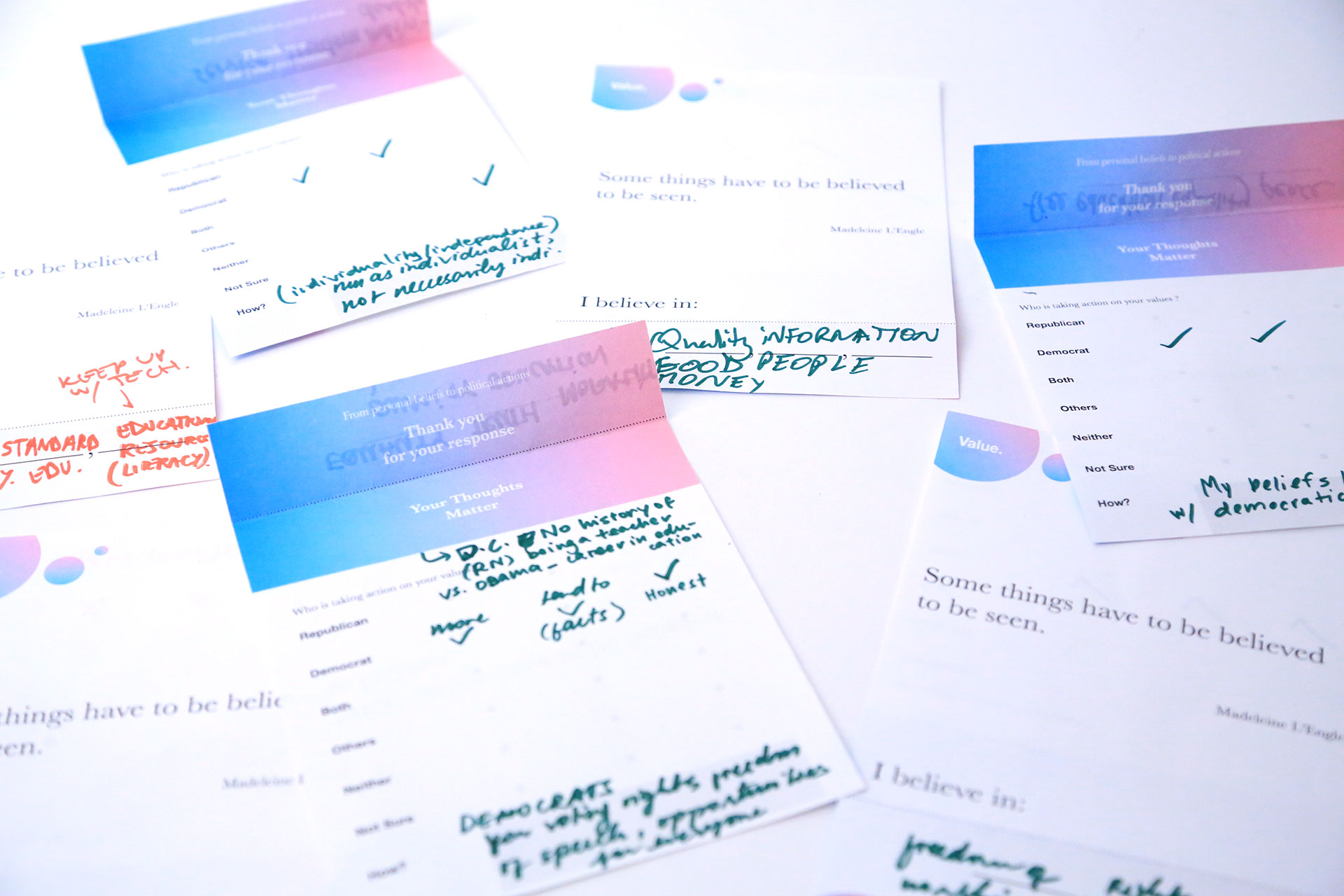

Provocation: “I BELIEVE”

Initiating Question: “What are people's personal values and do they think any governmental bodies taking action on those values?”

Team: Phuong Anh Nguyen, Anna Chau, Seona Joung, Micah Lynn, Eugenia Ramos

Location: Penn Station

A staggering 41.9% of eligible Americans did not vote in the 2016 presidential election. Team “I Believe” wondered to what extent this inaction was induced by a gap between individuals’ personal values and the political actions taken by elected leaders.

“I Believe” is a survey that flips the script. On a simply designed form, participants are asked to write their three “top” values. When completed, a member of Team “I Believe” folds and flips the paper to show how their three values align with a “representation matrix.” Led by the question, “Who is taking action on your values?” participants choose from among the existing options: Republican, Democrat, Both, Neither, Other, Not Sure. Asking participants to identify which values are addressed by which political party - if at all – gave participants an opportunity to talk about how their values align with their vote.

The responses were fervent. Most indicated a clear distrust in the system, writing down “LIARS” in all capital letters to express their frustration on political leaders’ lack of action. Even those who align themselves politically with one party did not believe that their top three values were fulfilled by their party. A few revealed their values are better served by individuals rather than the parties. Only one out of twelve participants responded that one party aligned with all three values; but shared that it was because the party had a specific policy that helped the respondent keep their money.

Provocation “I Believe” validated the increasing vexation Americans have when they can only choose from polar opposites; and it asks what more can design do to forge spaces to co-create new systems, new opportunities and new courses of action. “I Believe” hopes to offer new options to the many who remain apathetic, disengaged and disaffected by the misalignment between their beliefs and those elected to represent them.

Provocation: “TRIGGER WORDS: ACTION OR APATHY”

Initiating Question: How does political messaging depress voter turnout or ignite positive action?

Team: Sophie Carrillo, Rhea Bhandari, Tzu-Ching Lin, Yue Leng, Wes Rivell, Elvis Yang

Location: Chelsea Market

Provocation “Action or Apathy” sought to discover how trigger words engendered different emotional responses that either lead people to vote or sit the election out.

The design provocation took the form of a visual spectrum representing a range of emotions. Alongside the spectrum were potentially triggering words and phrases commonly heard in news coverage, debates and political advertising during the 2018 midterm elections, among them “immigrant caravan,” “alien,” “food stamps,” “healthcare,” “Facebook” and “Amazon.”

Participants were invited to choose words that trigger them and place them on the spectrum to indicate which words incited them to action and which led to feelings of powerlessness. They were then asked to talk about the emotions each word made them feel: enraged, traumatized, concerned, overwhelmed, discouraged, sad, neutral, excited, empowered, hopeful. The emotional responses were left open-ended so that participants could choose their own descriptive language and engage in a non-partisan conversation about their feelings, fears and hopes.

The critical element of the provocation was the spectrum, as it attempted to visualize the complexity of emotions and actions rather than identifying political feelings or actions as living only in a binary state: good or bad; us or them; liberal or conservative.

People were eager to express their feelings on these current topics, most of them were looking for outlets to talk about their rage, anger or just generally how excited they were about other not so controversial issues. As most of them were words, people had different backgrounds and stories, for some people this triggered other events they would then add and place on the spectrum, others had discussions as they saw other participants spectrums and compare each other.

A further investigation might seek to discover the degree to which these reported responses led to actual action or apathy in the ensuing days, months or years. Do emotional triggers lead to long-lasting emotional or behavioral shifts; and how does political messaging leverage the distinction between emotions and action? Understanding these relationships could help create opportunities not only for discussion but to increase participation.