EATING TOGETHER: Explorations in an Anti-Social Food System

Will Lentz master’s thesis Eating Together: Explorations in an Anti-Social Food System promotes a resurgence in the social value of communal eating experiences. In a time when isolation and independence are increasingly common, Lentz offers products and provocations aimed at bringing people back together over food.

Please click on the following link to read Will's thesis book: https://issuu.com/lentzwc/docs/eatingtogetherexplorationsofasocial

This was, in part, inspired by regular encounters with ad campaigns for Seamless—a popular food delivery service. “I was seeing them everywhere,” Lentz recalled. “I remember feeling taken aback by the idea that people are being encouraged to avoid the essential human elements of food, the responsibility for its preparation, and the appreciation of the people involved in the process,” he emphasized. “Thinking about this regularly, I started to wonder what kinds of interactions might be able to create more value around our food experiences.”

In a time when isolation and independence are increasingly common, Lentz offers products and provocations aimed at bringing people back together over food.

To answer this question of re-valuing food experiences, Lentz looked for redefinition through the objects with which we eat, and he was increasingly convinced that physical behaviors were key. “First, I looked for answers in philosophy, and searched for conclusions about the impact of objects and spaces on the way we experience the world,” mentioned Lentz. It was within that pursuit that he came upon Thomas Wendt’s Design for Dasein, an assessment of Martin Heidegger’s phenomenological studies from the perspective of product design.

Wendt discussed the dominant power of a user’s intent in defining the meaning and purpose of an object, pointing out that “we could eat cereal with a baseball bat, and that would give it meaning as a cereal-eating device.” Lentz took this example and ran with it. At the same time, he drew inspiration from designers and inventors like Dominic Wilcox, who uses his work to reimagine everyday interactions with the world. All of this inspired Lentz to design Rawlings for Wheaties and subsequent products/provocations that rethink the way objects can change our behaviors around food.

“With the baseball bat, I was toying with the ability of the product to bring the championship experience to the breakfast table,” says Lentz, “flipping the idea of Wheaties putting champions on the field—looking anew at how tools and the way we use them can challenge and change our experiences at the table.”

Similarly, The Potbelly Table continued that narrative. Inspired by communal, group-oriented eating experiences like crawfish boils and clam bakes, Lentz fixed the serving dish as the centerpiece of the eating surface—encouraging diners to eat from a shared vessel instead of separate plates.

Commensality—literally meaning eating at the same table—is the concept of creating and reinforcing social relationships around food.

Tables

Throughout, Lentz kept returning to the troublesome Seamless ads. “I couldn’t stop thinking about how much behavioral impact was being created by Seamless and similar products and services,” he noted, explaining an urge he felt to address the impact of digital products on our social lives. Similar products, including MealPal, and other online food-ordering services are notable for the avoidance behaviors they promote in providing people with convenient and independent dining opportunities. He saw a void that needed to be filled in successful food services that encourage people to eat together socially. The result was Tables—a digital platform that connects people in different social circles over home-cooked meals.

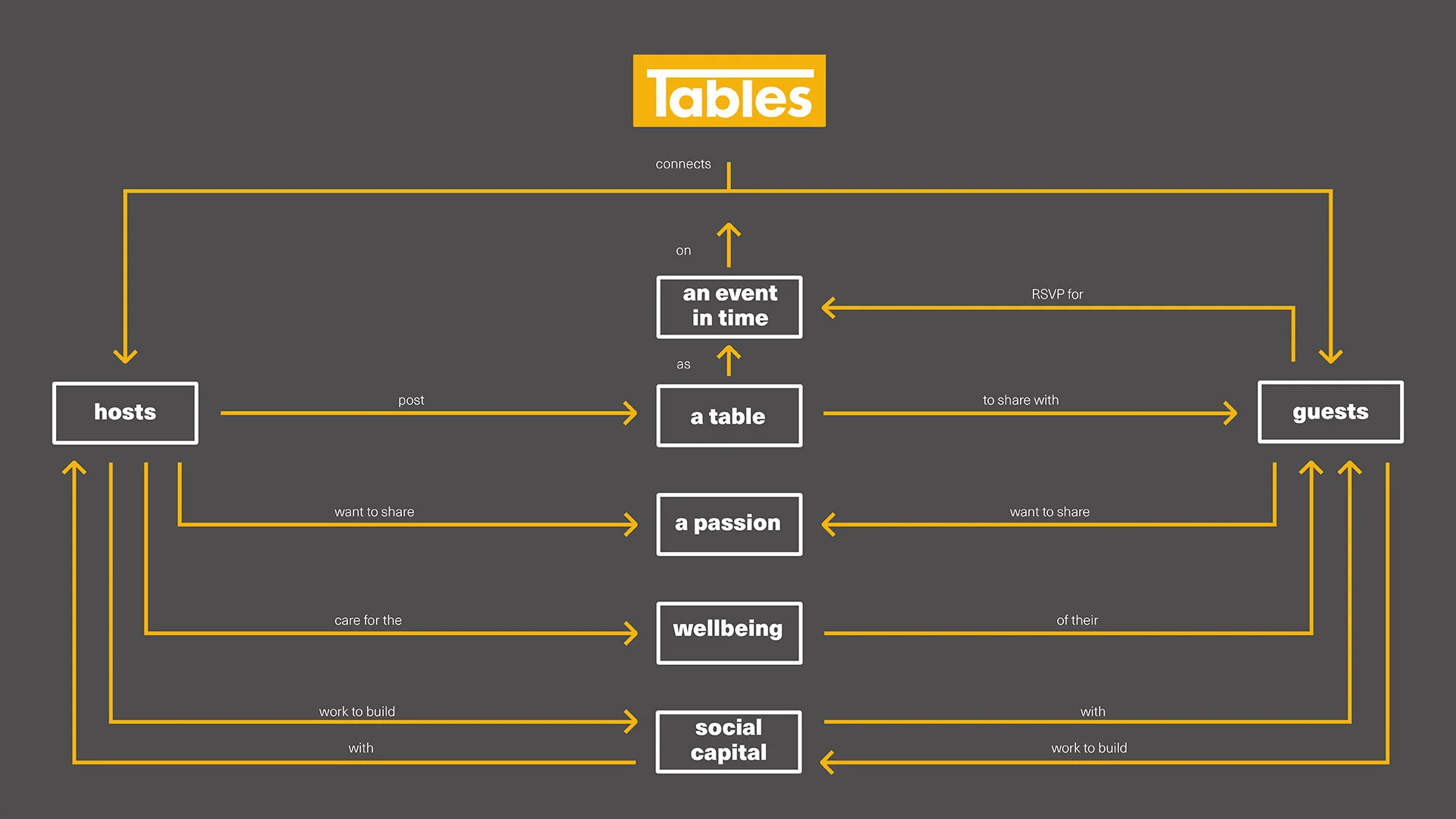

The app is Lentz’s attempt to bring commensality back into the American lifestyle. Commensality—literally meaning eating at the same table—is the concept of creating and reinforcing social relationships around food. Tables uses the binary of host and guest to help people build new commensal circles.

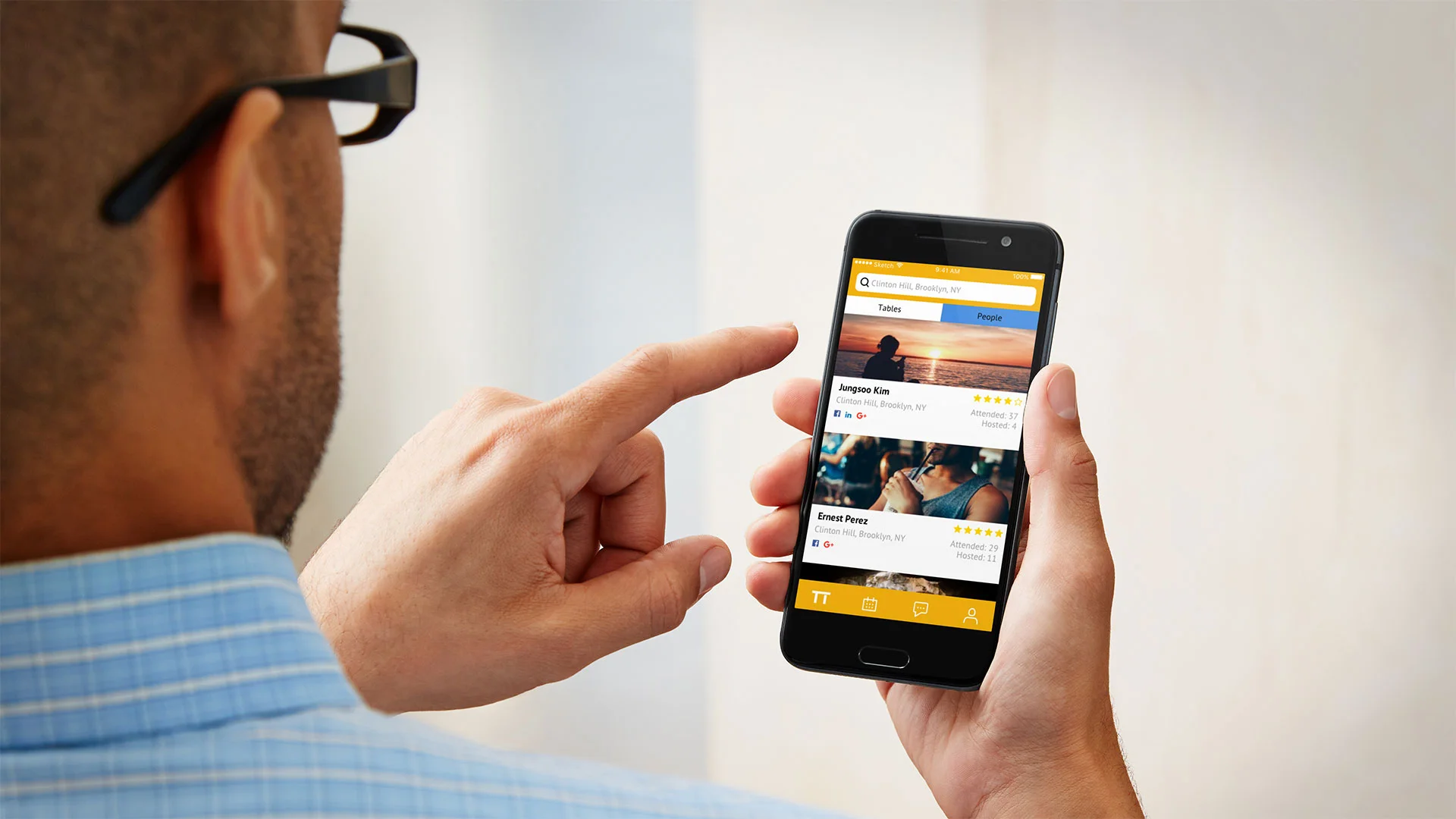

Hosts have a table and a meal that they’d like to share, and a topic they’re passionate about. They post their table in the form of an event, and guests can RSVP, based on their own interests. The meal itself is a facilitator for new social interactions.

In early user testing, Lentz determined that users spend the most time between a table and other people’s profiles. This observation is leveraged through the final execution of the prototype, in which everything is focused on social capital, putting user information first. Tables aims to be transparent by focusing more on the development of social connections than just the satisfaction of the meal.

While it may seem incongruous to counter damaging digital services with another digital service, Lentz defends the strategy. He argues, “In truth, there is good work to be done here. Our digital tools are an extension of our social selves. They’re already engrained in our behaviors and there’s an opportunity to leverage that. Tables focuses on ideas of hospitality and social reputation in that way,” says Lentz. “And I actually carry that idea into my physical products as well.”

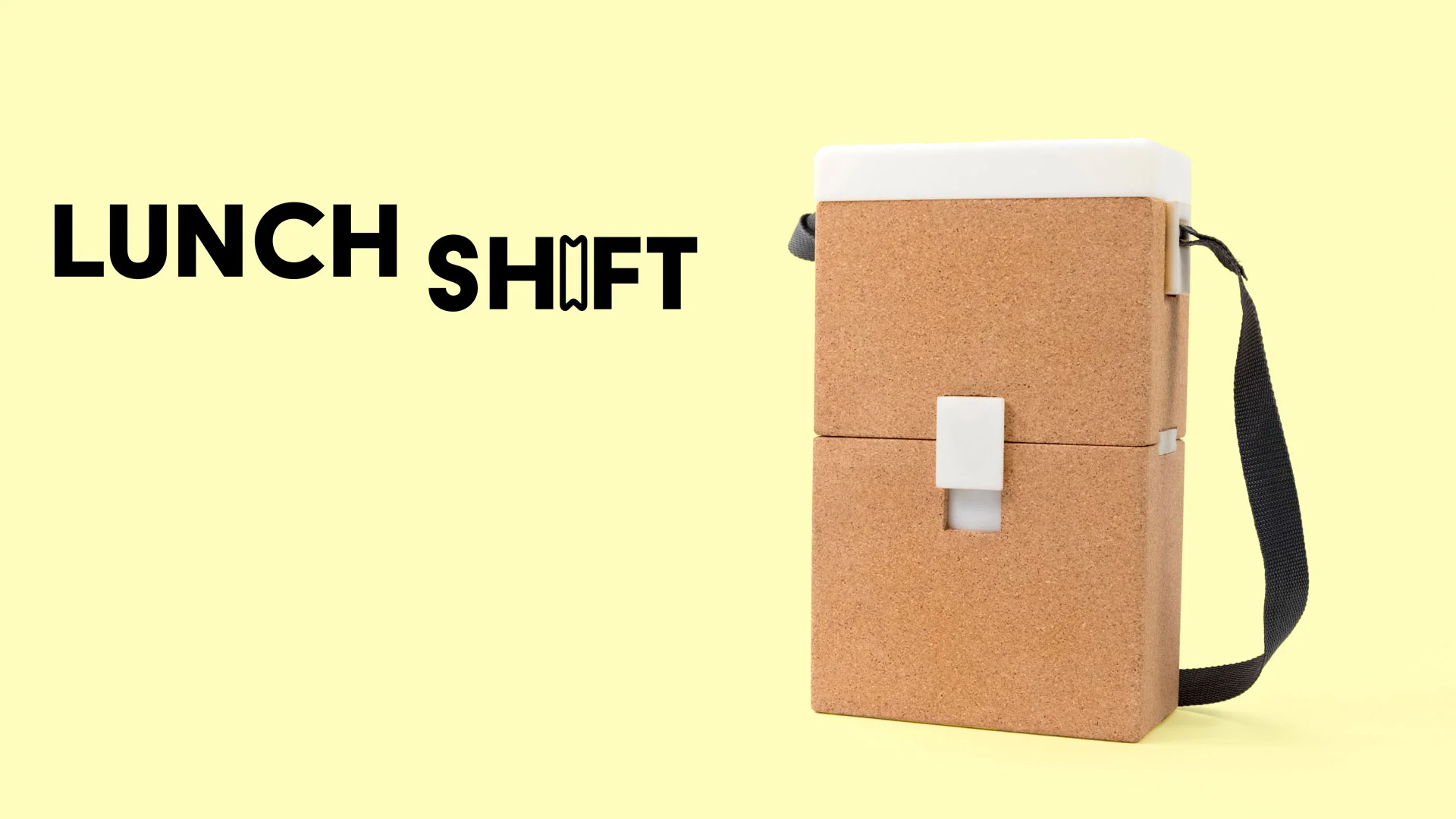

Lunch Shift takes the traditional lunchbox and transforms it into a mechanism that fosters a shared experience of hospitality.

Lunch Shift

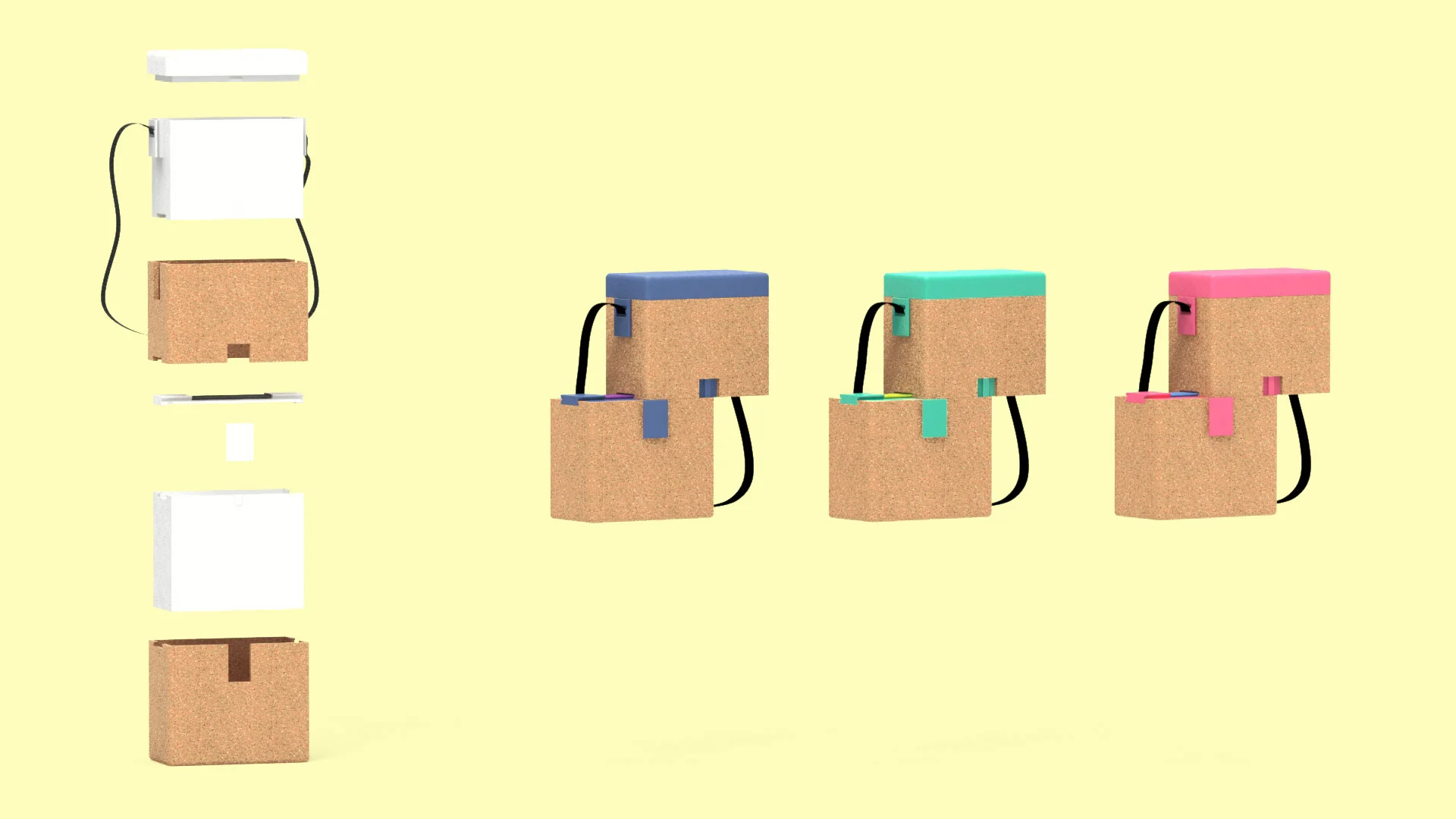

Lunch Shift is a lunchbox Lentz designed for two people. This product takes the traditional lunchbox and transforms it into a mechanism that fosters a shared experience of hospitality. Two people share a lunch break or “shift.” One person prepares lunch for both—with a serving in each half of the box. They then bring the box to share with their colleague or friend. The colleague/friend then takes the Lunch Shift and is responsible for the following day’s meal. Wash, rinse, and repeat.

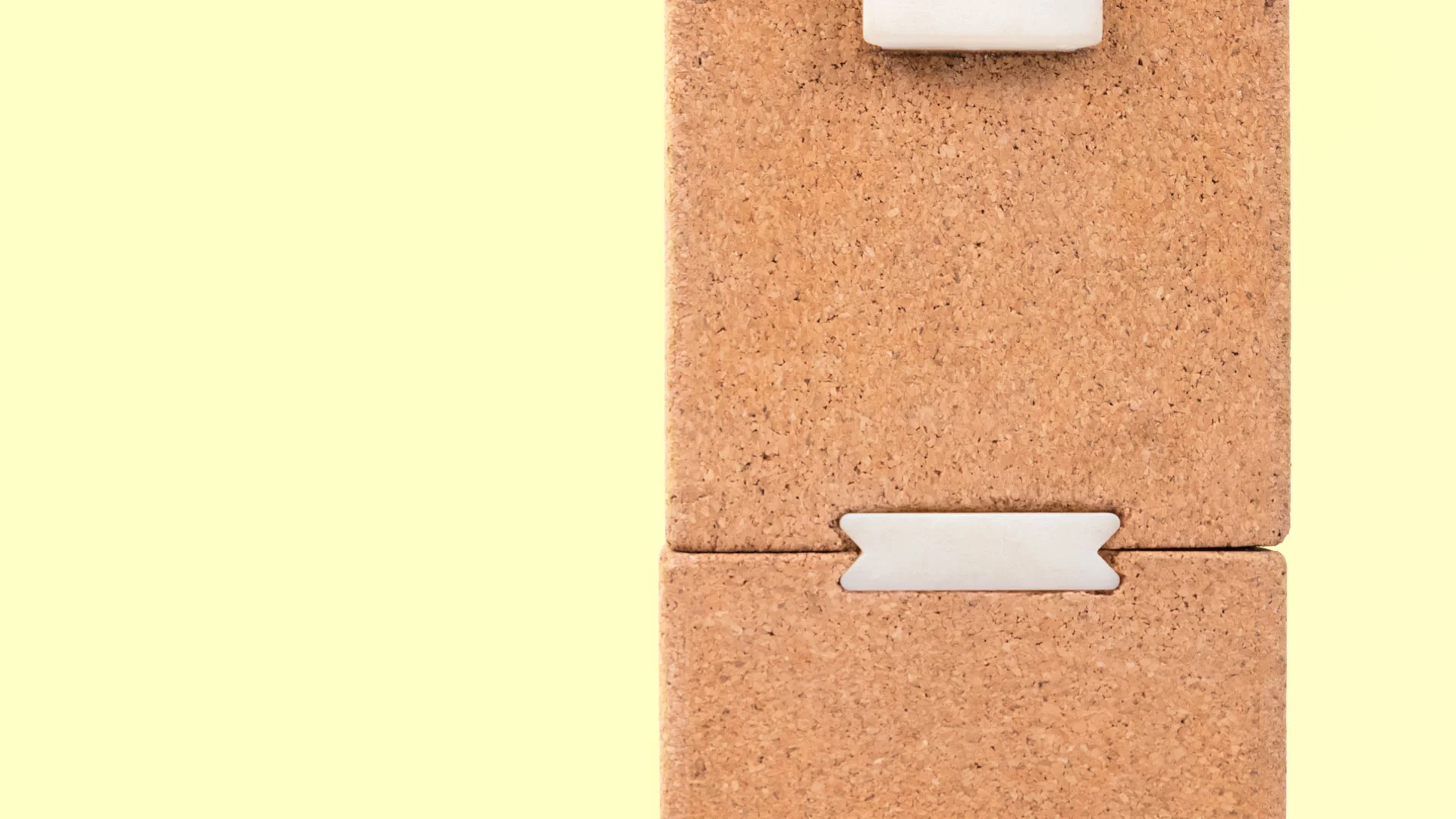

"The most elegant detail is the dovetail joint that binds the two halves of the lunchbox together," argues Lentz. "It’s the cornerstone of the whole interaction." The two boxes slot together, making it manageable by one person. The dovetail also acts as an indicator that each piece is part of something bigger. Lentz explains this feature in detail, “I wanted it to feel like the two parts were joined all of the time, even when they’re separated from each other. So, I introduced the dovetail as a mechanism for connection and union that’s always there.” Lentz states, “The dovetail is also the secret behind how the bottom lunchbox’s lid works. In that dovetail joint, the second handle is concealed, so that you can easily tuck the two lunchboxes back together or separate them to carry them individually.”

At any given point, the dovetail joint maintains Lentz’s intended sense of hospitality as a reminder that yours is only one half of a two-person meal. This is a reiteration of his mission—a resurgence of commensality. By making and sharing a meal for and with someone else, the provider is committing to a commensal relationship with the other participant. In his ultimate vision, that burgeoning commensal relationship repeats endlessly as participants take turns preparing the Lunch Shift.

“I want to continue building a set of tools that give people more opportunities to communicate through shared eating experiences.”

Collaboreating

Lentz developed Collaboreating, a social dining experiment that leverages physical objects in order to augment commensal experiences. Unlike Lunch Shift, these are not everyday objects, and this isn’t an everyday experience. Collaboreating uses a key element of more intimate experience design—an inner circle of trust in which everyday rules can be changed or broken. In this case, the objects morph the standard relationships between server and eater.

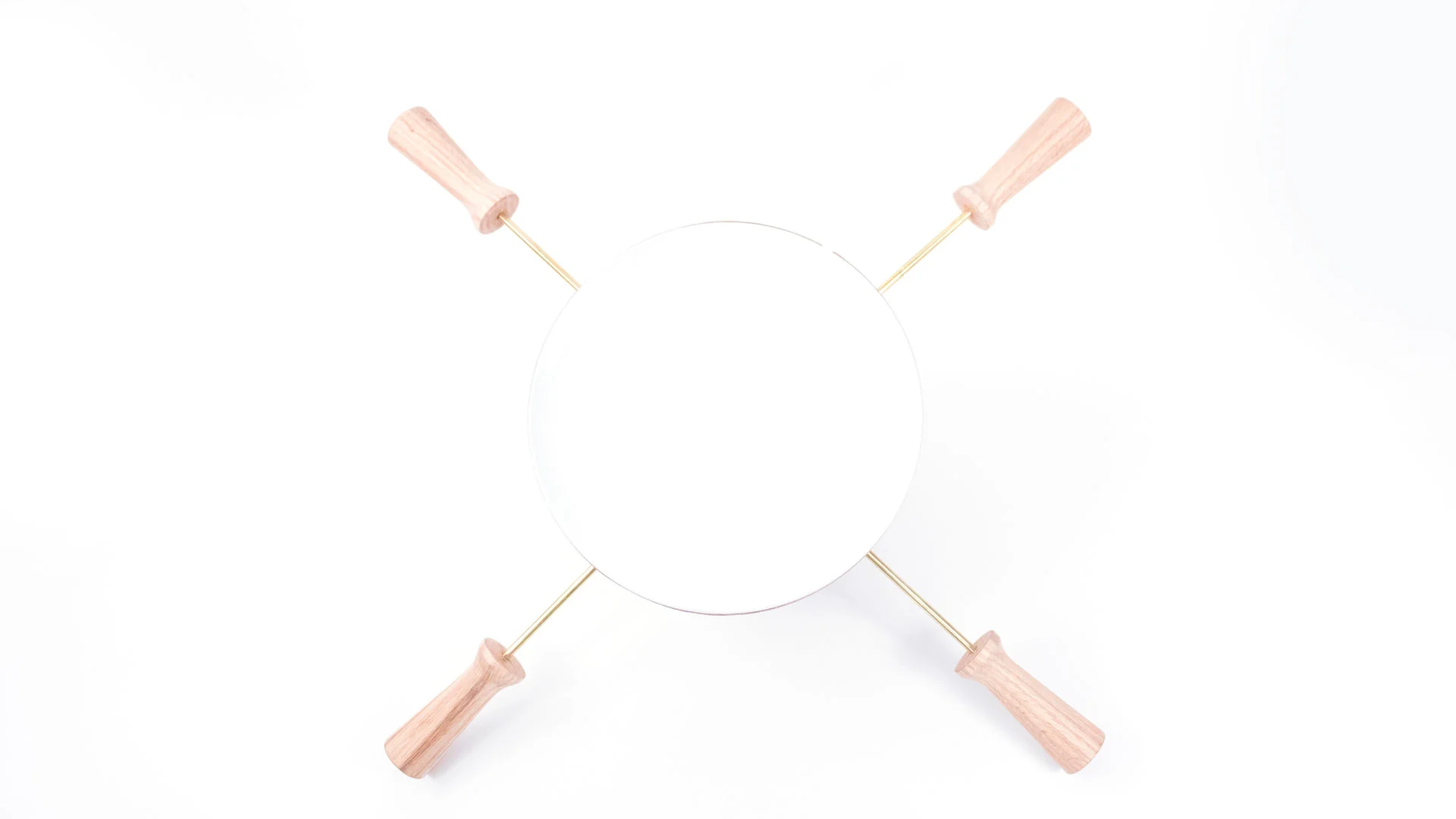

The Collaboreating experience builds on four interactions. The first is called Balance. Playing upon plate passing at a traditional family-style dinner, Balance never allows users to put down the serving dish until empty.

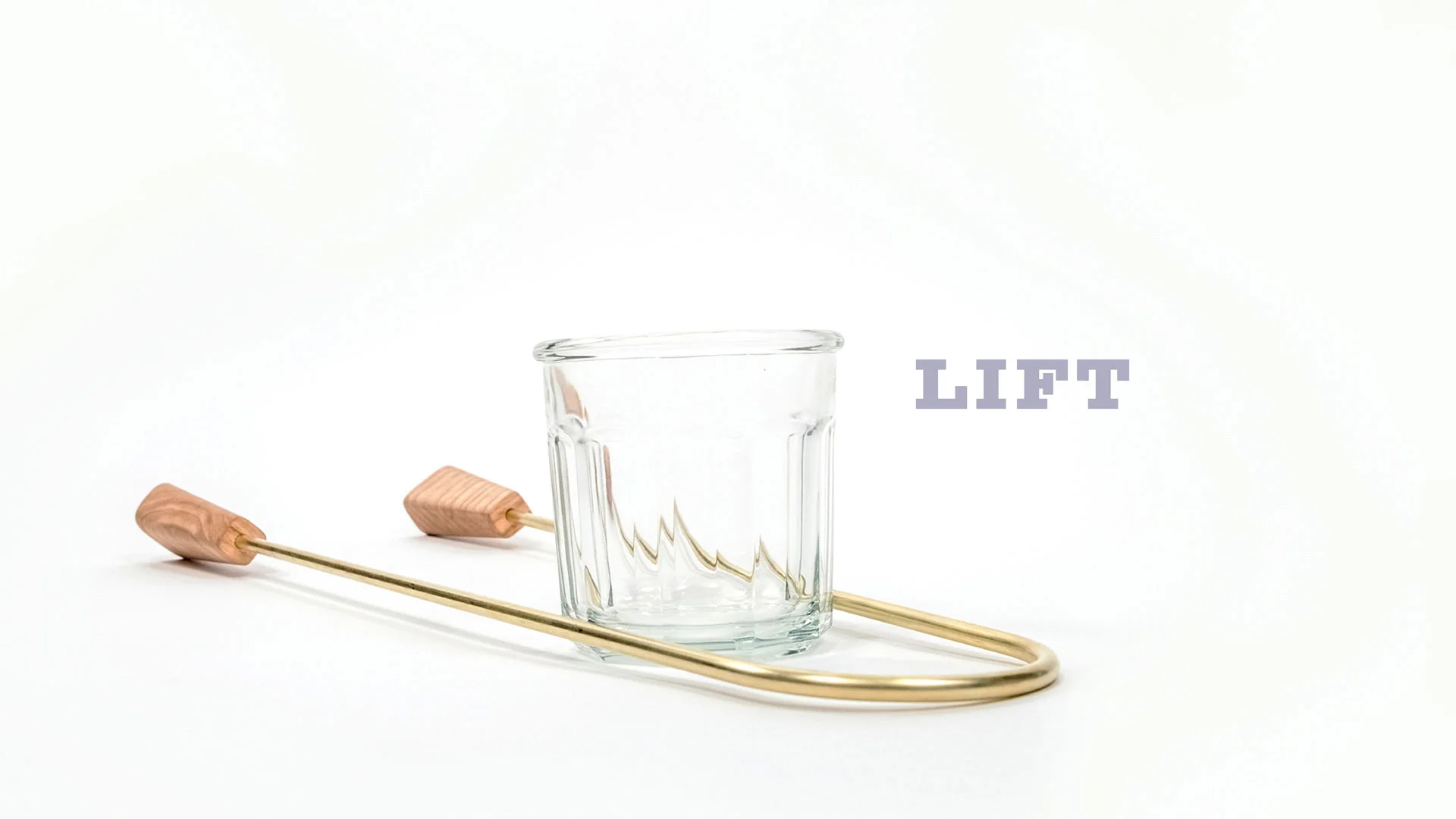

The second is Lift. Lift requires some extra coordination between server and eater. Using a set of rails for control, this interaction gives command of a guest’s drinking glass to their neighbor.

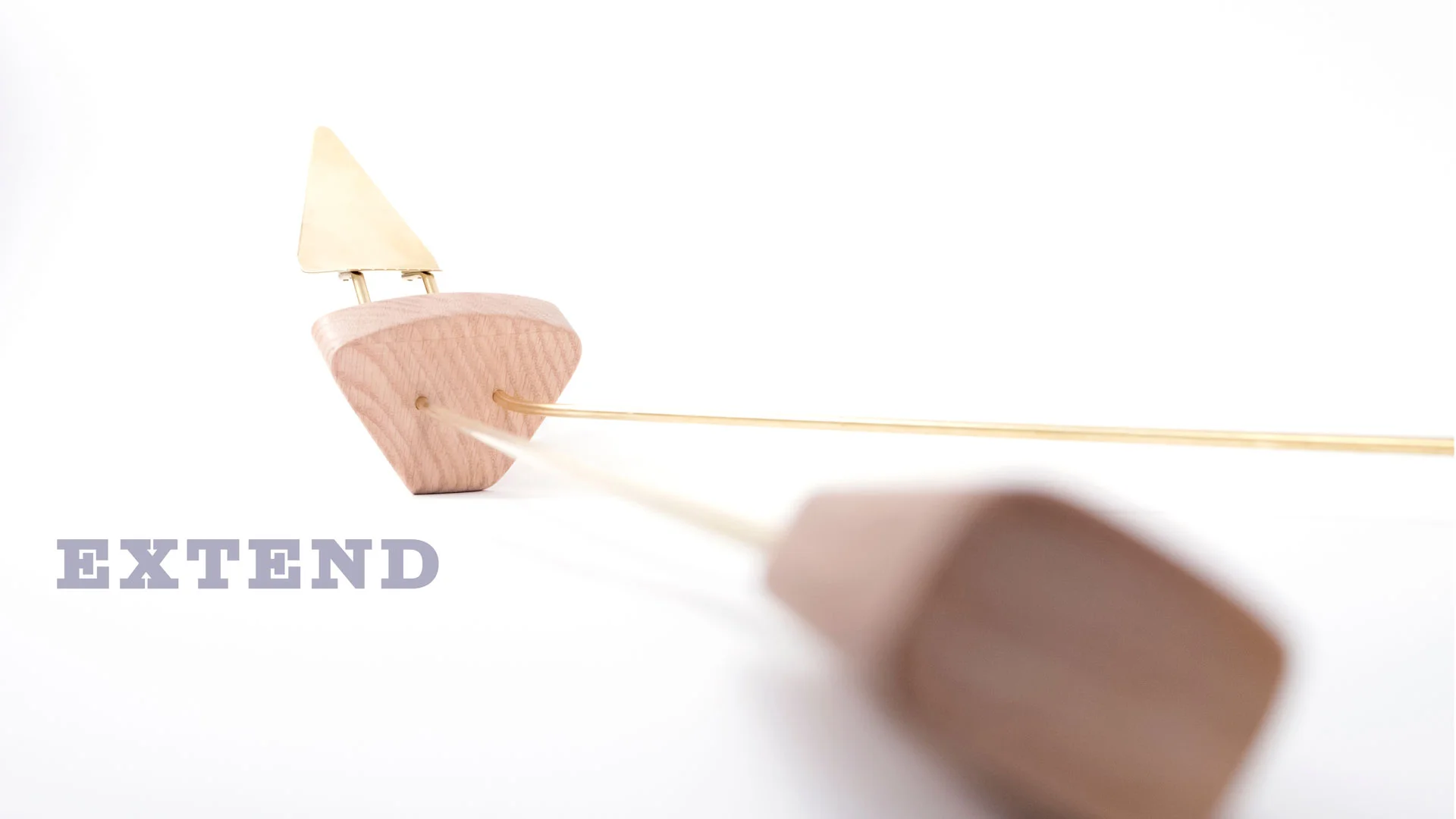

The third interaction is Extend. Extend utilizes a pie server that’s been stretched to the length of the table. With widespread handles, it requires two guests to work together to serve a third. “What was amazing was the willingness of guests to accept the rules I gave them, and to push them even further, getting the objects away from the table, finding functions that they didn’t already have,” said Lentz.

At the end of the experience, guests were called to action with a fourth and final interaction—the Sharing Spoon. The Sharing Spoon is a pair of connected spoons, much like take-out chopsticks. The joined spoons serve as an invitation to eat together. One participant breaks the spoons in half, offering the second spoon to a companion, and keeping the other as a kind of contract or agreement to share a moment of commensality.

“This is where Collaboreating is going next,” promises Lentz. “Out into the world to be shared by others. I want to continue building a set of tools that give people more opportunities to communicate through shared eating experiences.” His plans don’t stop with the gesture of an invitation. His enthusiasm for the project shows when he talks about the Sharing Spoon with plans to make them not only easy to acquire and share, but also to use. “That’s the future of the spoon,” he said, “an actual shared tool for eating. They’ll function as real spoons in the end. Look for a Kickstarter project in the future.” Looking forward, Lentz remains committed to Collaboreating, with plans to expand his involvement in the resurgence of commensal behaviors in the world.

Learn more about Will Lentz's work at willclentz.com, and contact him at will.c.lentz[at]gmail[dot]com.