JUSTICE BY ALL: Revitalizing Civic Engagement in the Judicial System

Julia Lindpaintner’s thesis work was inspired by her own experience of serving on a grand jury in Manhattan during the summer of 2016. It profoundly changed her understanding of the judicial system, and in particular, the way she saw her role in it. “My mental model shifted,” Julia states. She further explains, “Instead of seeing the judicial system as an autonomous force over which I had no influence, I felt viscerally the way in which we, as citizens, are collectively responsible for the system and the outcomes it produces.”

“I felt viscerally the way in which we, as citizens, are collectively responsible for the system, and the outcomes it produces.”

This insight inspired her thesis title, “Justice by All.” She devoted her work to exploring ways to revitalize civic engagement in the judicial system by asking the question, “How can I, as an individual, contribute to more just outcomes?”

Julia began by investigating the historical relationship between the public and the judicial system. According to legal scholar Andrew Guthrie Ferguson, “The jury once existed at the core of American constitutional identity… At the founding, jury service and voting were twin political rights, equal in stature and importance.”

Juries were originally instated as a way for the public to protect themselves against the potential tyranny of government, and throughout American history, jurors have played an important role in protesting laws they considered unjust. Although people tend to dread receiving jury summonses nowadays, studies have found that when people do participate, they feel more politically engaged and community oriented afterwards, and report a higher trust in the system.

While interviewing justice reform advocates at the Center for Court Innovation, Julia learned that community engagement is essential in building public trust even outside of jury duty, and that many court reform efforts today focus on procedural justice. Procedural justice describes the idea that in terms of building public trust, the perceived fairness of court processes is more important than the perceived fairness of outcomes. Places like the Red Hook Community Justice Center in Brooklyn focus on transparent and participatory processes in an effort to constantly be demonstrating the legitimacy of the system. As a result, they see greater compliance with court orders and lower rates recidivism.

Based on her research, Julia synthesized a theory of change: “To produce more just outcomes,” she argues, “there needs to be trust in the system. In order to build trust in the system, procedural justice is required. And to achieve procedural justice, the system must provide transparency and the opportunity to participate.”

By taking a human-centered approach, Julia believes designers can promote both transparency and participation in the judicial system by reimagining current points of interaction and inventing new ones. To that end, she took a holistic view by looking at the topic through a variety of design lenses and creating interventions that fall along a continuum from the judicial space to the civic space—or more simply put—from the courts to the streets.

“We have to make jury duty feel like a privilege, not a pain.”

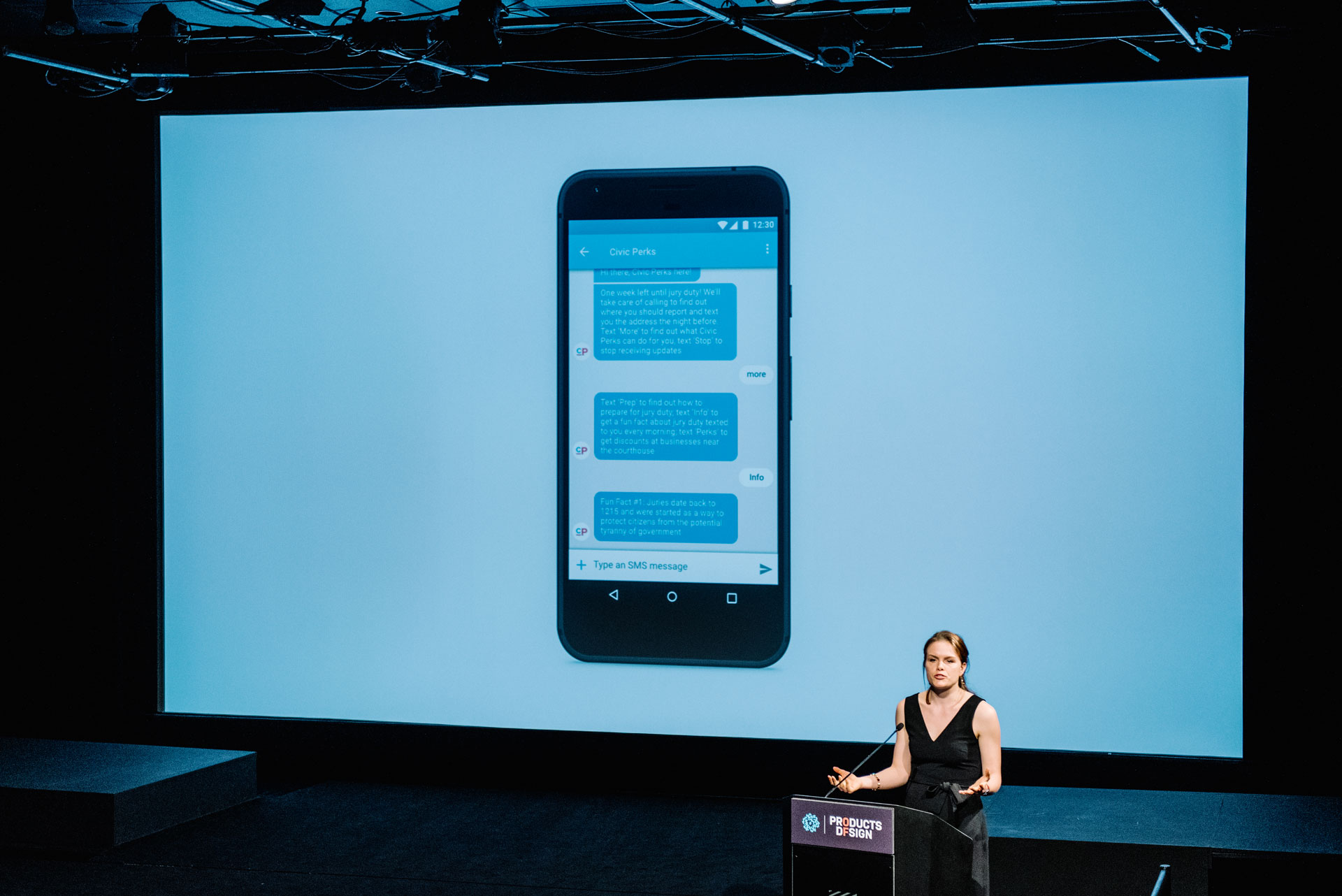

Civic Perks

Beginning with an existing interaction, Julia found that the apathy around jury duty was reflected in low juror turnout rates across the country. Kirsten Tynan, director of the Fully Informed Jury Association, told Julia that public perception around jury duty had to shift. “My goal became to make jury duty feel like a privilege, not a pain,” says Julia.

She designed Civic Perks to respond to this need. A service designed to transform the narrative and experience of jury duty, Civic Perks meets jurors right on their summons, softening the blow by inviting them to sign up for a text messaging service. At its most basic, Civic Perks will send a prospective juror text message reminders about when and where to show up. This is not a new idea—SMS services like this have been very effective in courts around the country. But Civic Perks takes it a step further.

“Jurors get discounts;

local businesses get more foot traffic.”

Using a chatbot and conversational user interface, Civic Perks provides context and lets jurors know how to prepare and what to expect. Civic Perks also wants to reward jurors and strengthen the community, so its business model leverages its connection with jurors by offering hyperlocal marketing opportunities to businesses near the courthouse. Jurors get discounts; local businesses get more foot traffic.

When the experience concludes, Civic Perks sends jurors a “Thank You” pin to wear as a badge of honor, just like people do with an “I Voted” Sticker.

Court Guide

Looking at interactions beyond jury duty, Julia had the opportunity to collaborate with designers at Zago on an initiative—led by the Center for Court Innovation—to enhance procedural justice at Manhattan Criminal Court through physical interventions in the space. The effort focused on improving four elements of procedural justice, as articulated by Tom Tyler, a thought leader in the field: being shown respect; feeling able to participate; perceiving the process as unbiased; and, viewing the judge as trustworthy.

Julia began to wonder, could this start even before someone reaches the courthouse? Currently, there are few resources to consult when a new juror wants to find out what to expect in court. One can visit the court website, which is comprehensive but hard to parse—or turn to Yelp. Setting out to apply the tenets of procedural justice to create a digital resource for all court visitors, Julia designed Court Guide.

To begin, she did the following: she mapped the vast content that she wanted Court Guide to offer; developed proto-personas to explore possible use case scenarios; made paper prototypes to test user flow; and, ran a card sorting exercise to validate the information architecture. For the visual design, she studied and applied Google’s material design standards and created custom iconography.

All this came together in a user interface with simple, friendly graphics and straightforward language, making information both accessible and digestible. The app invites participation with multiple opportunities for user feedback. It serves people coming for hearings and jury duty. Julia even used it as a provocation to think about how courts could enlist volunteers to enhance procedural justice.

Observing public reaction to the travel ban and the subsequent swift judicial action proved that citizens can and do engage with the system from the outside, too.

As the political reality shifted in early months of 2017, Julia’s thesis work shifted, too. While her early explorations focused on interactions inside the system, observing public reaction to the travel ban and the subsequent swift judicial action proved to Julia that citizens can and do engage with the system from the outside, too. This prompted an exploration of ways to engage with and impact the system within the civic space.

Julia saw the opportunity to create a product that could simultaneously embolden & inform those new to protesting.

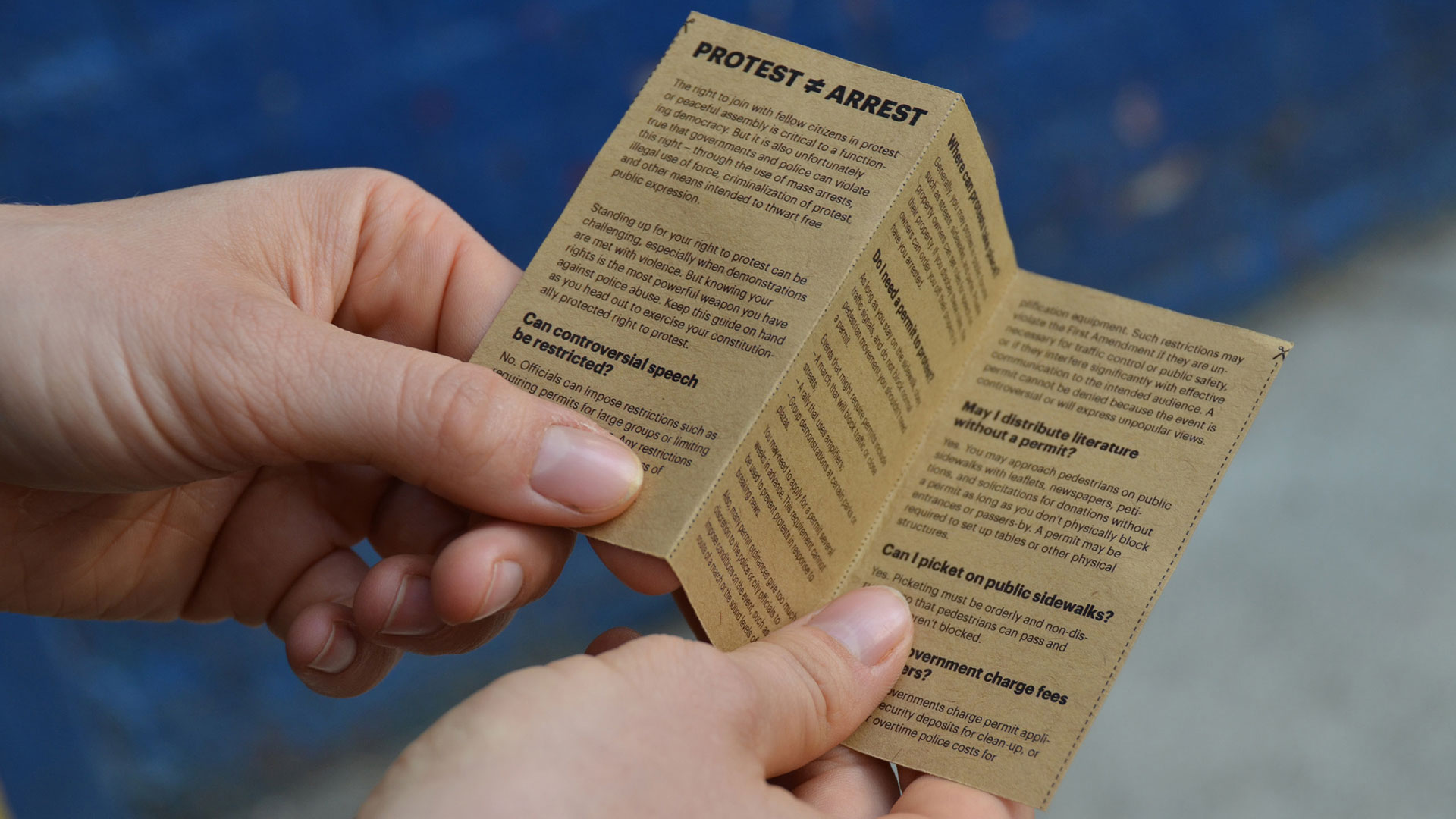

Protest≠Arrest

Inspired by a news story about how arrests of protesters at Standing Rock were overwhelming the North Dakota court system, Julia saw the opportunity to create a product that could simultaneously embolden and inform those new to protesting. She took the existing practice of protesters writing the phone number of legal services on their arms and created Protest≠Arrest.

Protest≠Arrest is a set of temporary tattoos that Julia proposed producing in partnership with Tattly, the ACLU, and, for the case of Standing Rock, 350.org. The set includes declarative tattoos that are meant to be worn visibly. The centerpiece is a tattoo that arms the wearer with reminders about their rights, how to talk to police, and how to get legal help. The packaging folds down and has a second life as a pocket-sized guide to your rights.

In Solidarity

While protests may be the dominant way in which citizens engage with the system from the outside, they are sporadic and do not appeal to everybody. In order to lower the barrier to civic engagement and make it accessible to everyone, every day, Julia designed In Solidarity.

With a window for printed messages as well as a whiteboard insert, the In Solidarity tote bag encourages its owner to take a stand publicly and act as a personal billboard for a larger cause. Subverting the existing typology of branded bags—which turn their carriers into walking advertisements—the In Solidarity bag allows you disseminate information, raise awareness, or call others to action—whether by printing new messages or writing one’s own.

Dance/Rally is a mash up of existing typologies: It combines the political engagement of protests with the joy of dance flash mobs.

Dance/Rally

To further drive engagement, Julia drew on her background as a dancer and used the principles of experience design to formulate a new mode of civic action—one that would attract audiences who might otherwise feel disconnected and amplify the voices of those already engaged. Dance/Rally is a mash up of existing typologies—it combines the political engagement of protests with the joy of dance flash mobs.

As a proof of concept, she partnered with the Columbia School of Social Work’s chapter of the Southern Poverty Law Center on Raise the Age—a campaign that urged state legislators to raise the age of criminal responsibility, and cease the prosecution of 16- and 17-year olds as adults. By creating branded content, Julia was able to rapidly develop a social media presence, through which she could boost engagement with the issue. She choreographed a simple dance to the Twisted Sister song “We’re Not Gonna Take It,” filmed a tutorial video, and recruited participants. On March 25, 2017, demonstrators and dancers gathered in front of City Hall.

“I believe that in order to reach justice for all, we will need justice by all.”

The Raise the Age legislation was passed in early April of 2017, just a few weeks after the Dance/Rally, and Julia considers everyone who participated as sharing in that victory. She is firmly convinced that the public’s participation in the judicial system is essential. As she puts it, “I believe that in order to reach justice for all, we will need justice by all.”

Learn more about Julia Lindpaintner's work at www.julialindpaintner.com, and contact her at julia.lindpaintner@gmail.com.