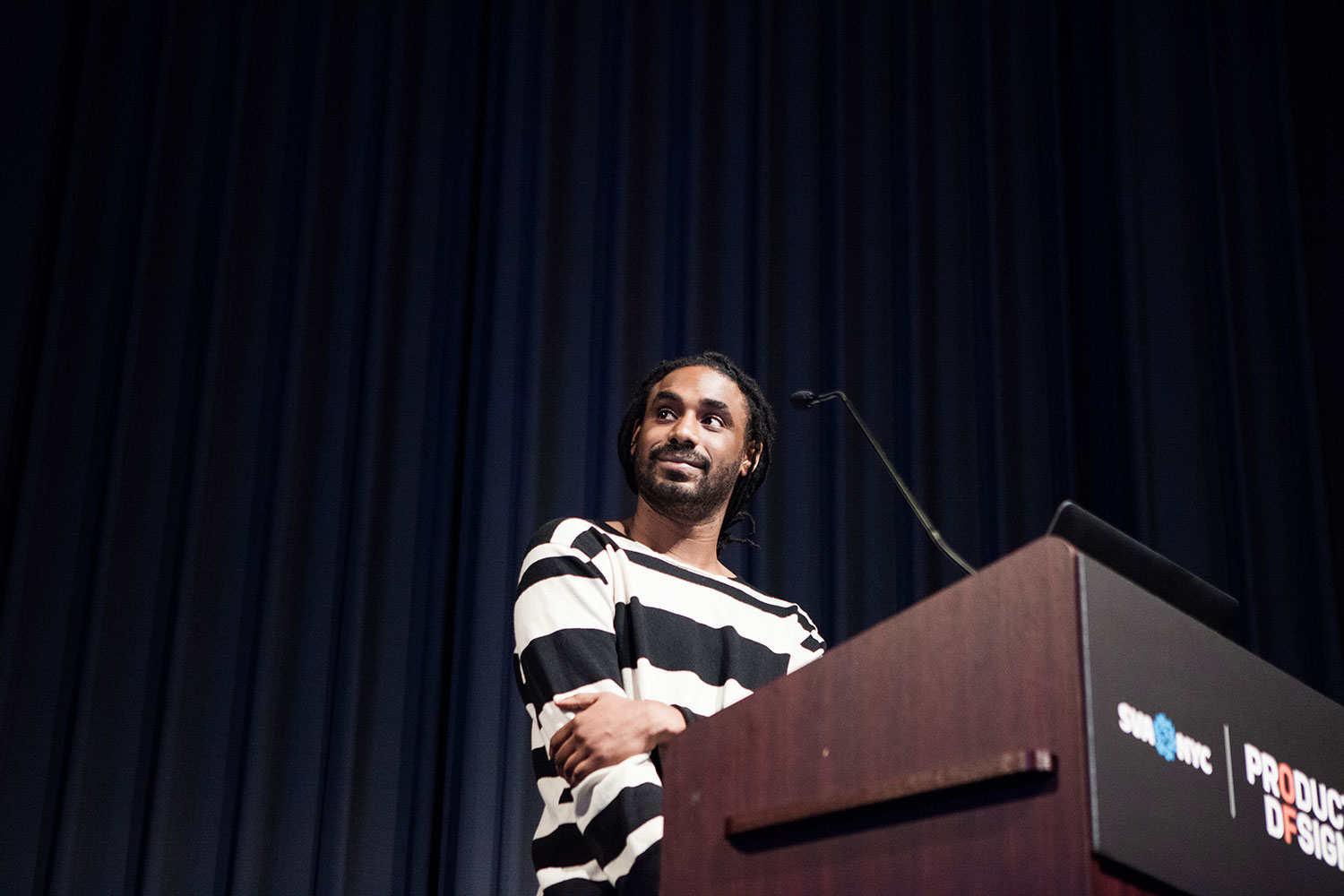

MASTERS THESIS: The Spectacle, by Brandon Washington

Brandon Washington’s master’s thesis, The Spectacle, is an investigation into Guy Debord’s theory of the same name and how it relates to today. The spectacle is a communication tool that employs fantasy in order to sell society on the idea of how we should live our lives, and what we should aspire to be. It manifests in many forms—social media, movies, television, store displays, political campaigns, sports, and entertainment. The spectacle urges us to watch and consume life instead of actively constructing our own—losing our grasp of our own desires and replacing them with others. Brandon’s thesis takes the form of an intervention, aiming to wake people up, expose them to alternative and freethinking, get them in touch with their own desires, and express their true selves.

The spectacle urges us to watch and consume life instead of actively constructing our own—losing our grasp of our own desires and replacing them with others.

The spectacle describes how the culture industry has weakened society’s ability to think critically by providing the key elements to distracting and stupefying the public. Guy Debord paints a picture of the spectacle in his book Society of the Spectacle, and created a group called The Situationist International to fight against it. The group stood by the belief that the wealth accumulated by society should not be used for mindless consumerism, but instead should be used to revolutionize that society. They did this by creating situations that disrupted everyday life in order to make people question the systems around them. The ultimate goal of this approach is to take away the limited view of the status quo, in order to construct one’s own.

We are a society engulfed by the spectacle. The spectacle is rooted in a neoliberal capitalist ideology—a free market where you have to pay to play. Capitalism promotes the idea of consumerism as a means to build and strengthen an economy. The more society buys and consumes, the more jobs are created. More jobs allow people to feel secure as far as their needs are concerned, but also provide people more expendable income that can then be used to buy more stuff. The problem is that consumers do not understand when enough is enough. We tend to want more objects than others. We need a bigger house than our neighbors, a better car, a higher paying job, and newer things. We constantly play this game of “keeping up with the Joneses,” and it has, in effect, become the status quo; it has become the dominant ideology.

It’s also an ideology has swept the globe as a mark of success. But this society is only utopia for the few born with great privilege. “Most of us will have to work our bones off to make this idea a reality,” Brandon argues. “Some of us will go further than others, chasing for so-called status. But it is evident that only a few can stand on the top of the mountain called capitalism; these have recently been branded as ‘the one percent.’ One percent of the population is a small number, yet millions of Americans want membership into that exclusive, yet almost impossible-to-join club."

“This is a strange, rather perverse, story, just to put it in very simple terms. It’s a story about us, people, being persuaded to spend money we don’t have on things we don’t need to create impressions that won’t last on people we don’t care about.” —Tim Jackson

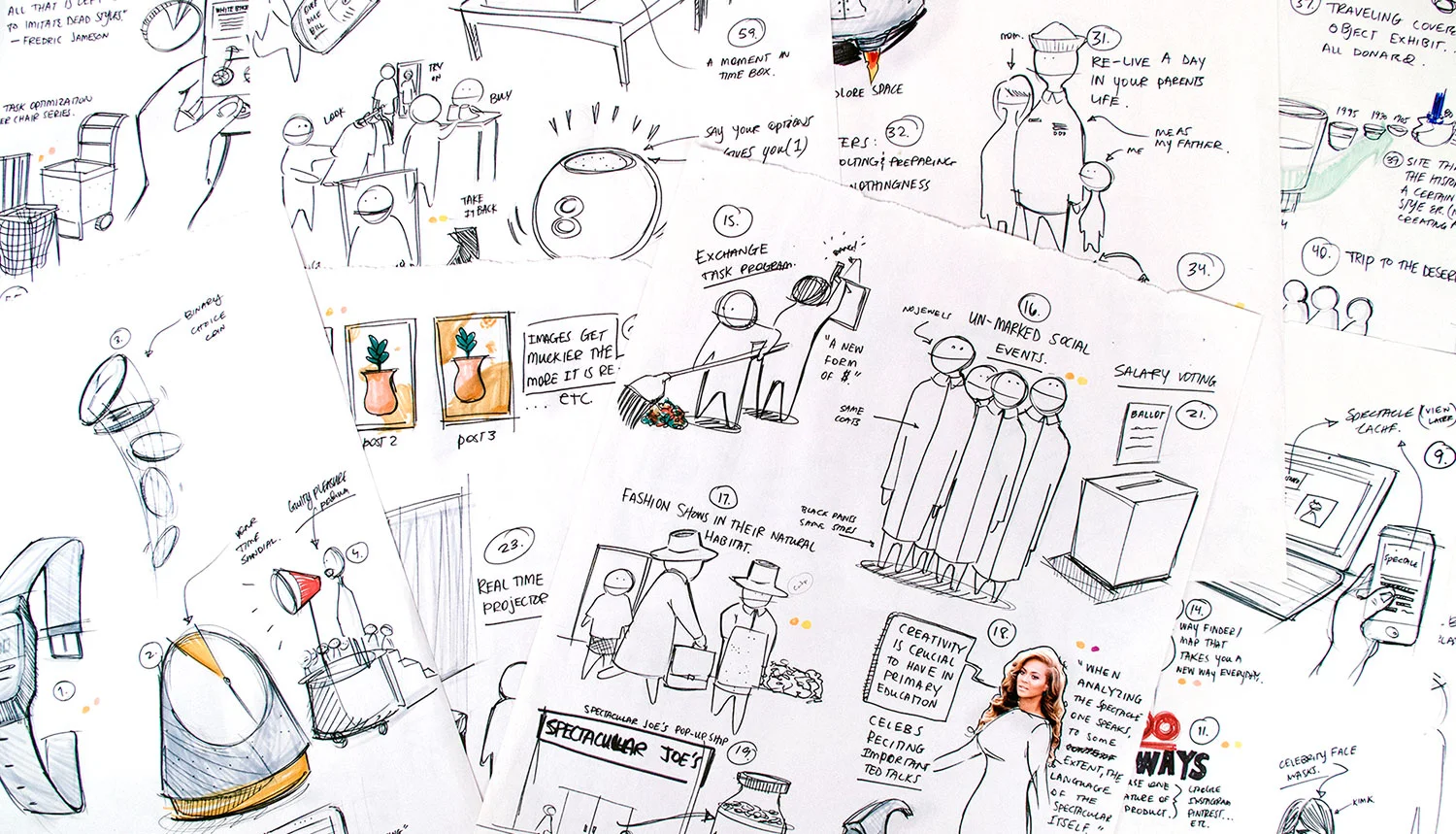

Brandon’s thesis is a contribution to fight this condition, and his initial explorations took the form of commentary. He created a set of editorial products that, by urning them into “boobie traps,” make people stop and think. For example, below is “furniture that is impossible to take apart when nestled together.”

Or perhaps a slippery welcome mat.

Although these interventions literally jostled people out of their expected moments, the work made Brandon realize that social commentary wasn’t a satisfying route to pursue, and so he redirected his sights towards an “ethical spectacle.”

An ethical spectacle has several criteria. It needs to be participatory, authentic about its message, open to everyone’s ideas, transparent, and aspirational.

The Ethical Spectacle

With insights gathered from speaking to experts, user research, prototyping, sketching, and system mapping, Brandon started to form a methodology to achieve the thesis goals. One of his biggest influencers was activist, educator, and author Stephen Duncombe, who coined the term “ethical spectacle” in his book Dream:Re-Imagining Progressive Politics in an Age of Fantasy. An ethical spectacle has several criteria. It needs to be participatory, authentic about its message, open to everyone’s ideas, transparent, and aspirational.

Brandon created “ethical spectacles” through a framework of three design lenses: service design, social enterprise, and a futuring.

ALT BOKS

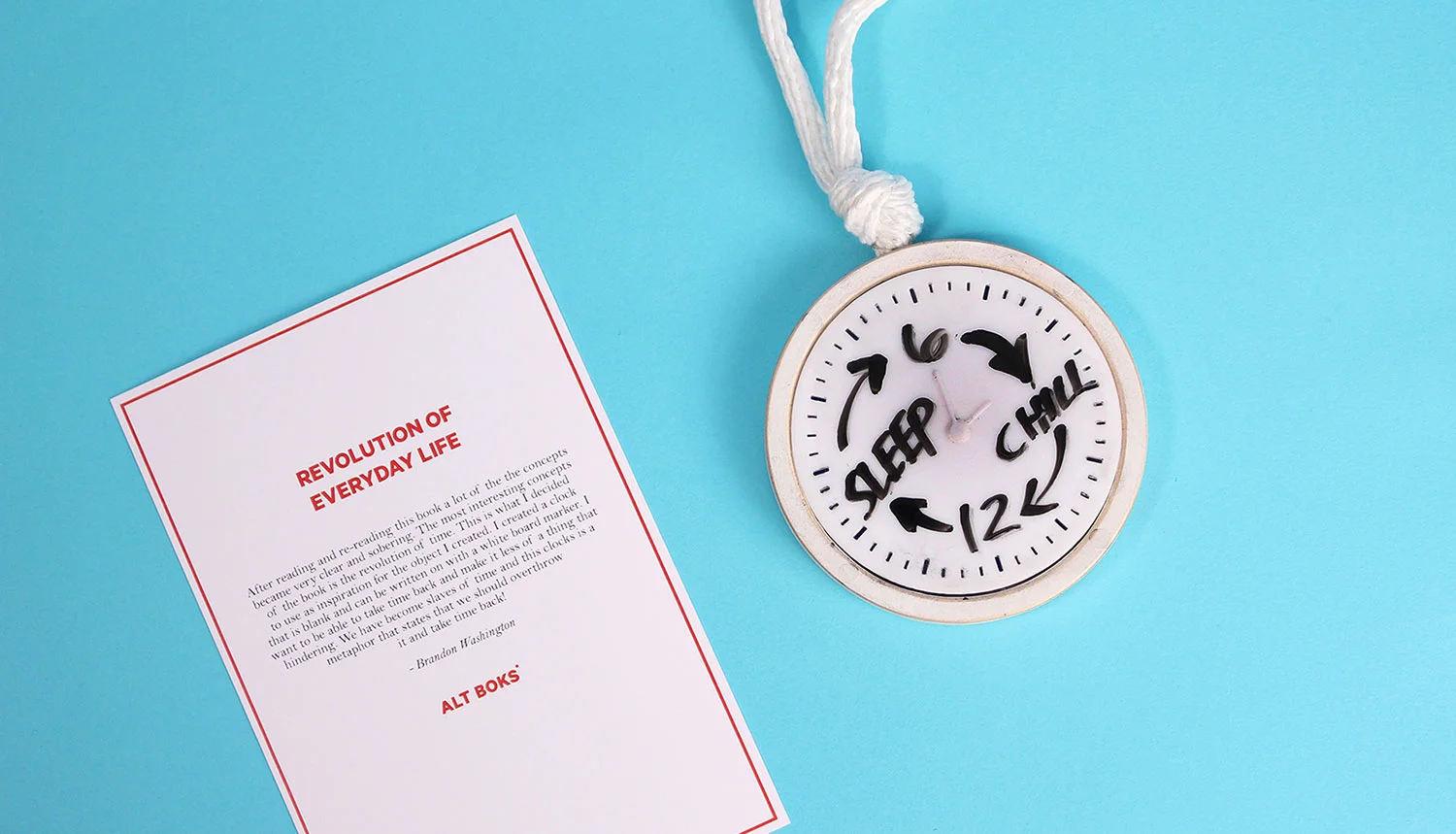

Brandon wanted to give people the materials to question society. His conversation with educator, activist, and founder of The Journal of Radical Shimming, Sam Gould, helped guide this pursuit. Here, he encouraged Brandon to use art as a vehicle for creating spaces for questioning culture. As a result, Brandon created ALT BOKS.

In 2013, nearly 70 million Americans visited a museum or gallery, or took part in an art event. Those of us living in major cities, immersed in art culture, can interact with this culture in tangible ways. But for people who do not live in these types of cities, interactions with art, in most cases, takes place through screens.

The ALT BOKS service is a mix between an arts CSA and a modern book club.

ALT BOKS wants to make this experience more tangible. It’s is a subscription-based service that disseminates “the materials of art that foster free thinking, expression, and questioning to those who don’t have art in their daily lives.” ALT BOKS distributes free thought from people whose art and writing are not widely publicized.

Subscribers receive one box every month for a year. There are six themes over that year—each grounded in critical and alternative thinking. New themes are introduced via a book, which is paired with a summary and suggestions on how to digest the book. The following month, subscribers receive an artist-commissioned object that is inspired by the book and theme. These are paired with a description of the artistic process of creating the object, along with the artist’s point of view on the topic.

The companion online platform features tutorials, artist talks, and a forum to discuss the themes and topics presented within the contents of ALT BOKS. In total, the service is a mix between an arts CSA and a modern book club.

Last Mile

Looking through the lens of a social enterprise, Last Mile is an attempt to take some of the power that fashion designers have, and to return it to the consumer. Here, rather than the producer’s or designer’s name emblazoned on the clothing, a “write-in” label is provided for the consumer to write their own name on as a gesture to claim ownership of the clothing purchased. The Last Mile shifts the power to the consumer by giving them ownership to present, curate, and realize their own spectacle. In doing so, the clothes become less about the maker and more about the wearer.

owever, with this power comes responsibility—the responsibility to understand where the clothes come from, and who created and produced them. Partnering with a company like Zady would be ideal for this program. Zady is a fashion-conscious retailer who presents customers with the origins of each piece of clothing that they sell. Taking the concept further, Brandon imagines all proceeds going to a non-profit such as Boot Strap, helping underprivileged creative people realize their dreams of becoming designers.

Brandon asked, “What if we turned the phone over, and literally wore our content on our chests?”

Projection

Last Mile inspired Brandon’s next project, Projection. The idea of owning, curating, and presenting your personal spectacle was the spark for a proposed future social behavior.

In the book Of System of Objects, Jean Baudrillard defines an object of consumption as a mere signifier of what that person represents. Brandon took the idea of signifiers in a literal sense, turning them into objects, and used the cell phone as a jumping off point.

Smartphones have allowed for multiple ways of communicating with others through multiple media. At the same time, they have contributed to a kind of voyeurism, insulating our consumption into a bubble. Brandon asked, “What if we turned the phone over, and literally wore our content on our chests?”

Here, the product allows users to project digital content out into the real world—creating a new form of social media in the physical sense. Like on platforms such as Instagram and Tumblr, the content that you choose to display on your Projection makes up—and represents—who you are. Whether it’s a political statement, a diary of your daily activities, or promotional content, Projection shows strangers on the street your point of view. But instead of being able to hide behind an avatar as is possible digital social media, the product forces you to stand behind what you believe in. Of course, Projection is quite a spectacle, but its content also sparked conversation and interest among test subjects.

Co-Creative Session

Returning to Stephen Duncombe’s argument that most ethical thing to do is to help connect people with their own desires—and to express them through spectacle—Brandon discovered a bright spot in the “five whys” method. The method was created by Sakichi Toyoda, and used within the Toyota Motor Corporation to discover the root cause of problems within his company. Simply asking a person “why” five times can uncover fundamental truths. Comedian Louis C.K. presents a light-hearted look at the technique in this popular television clip:

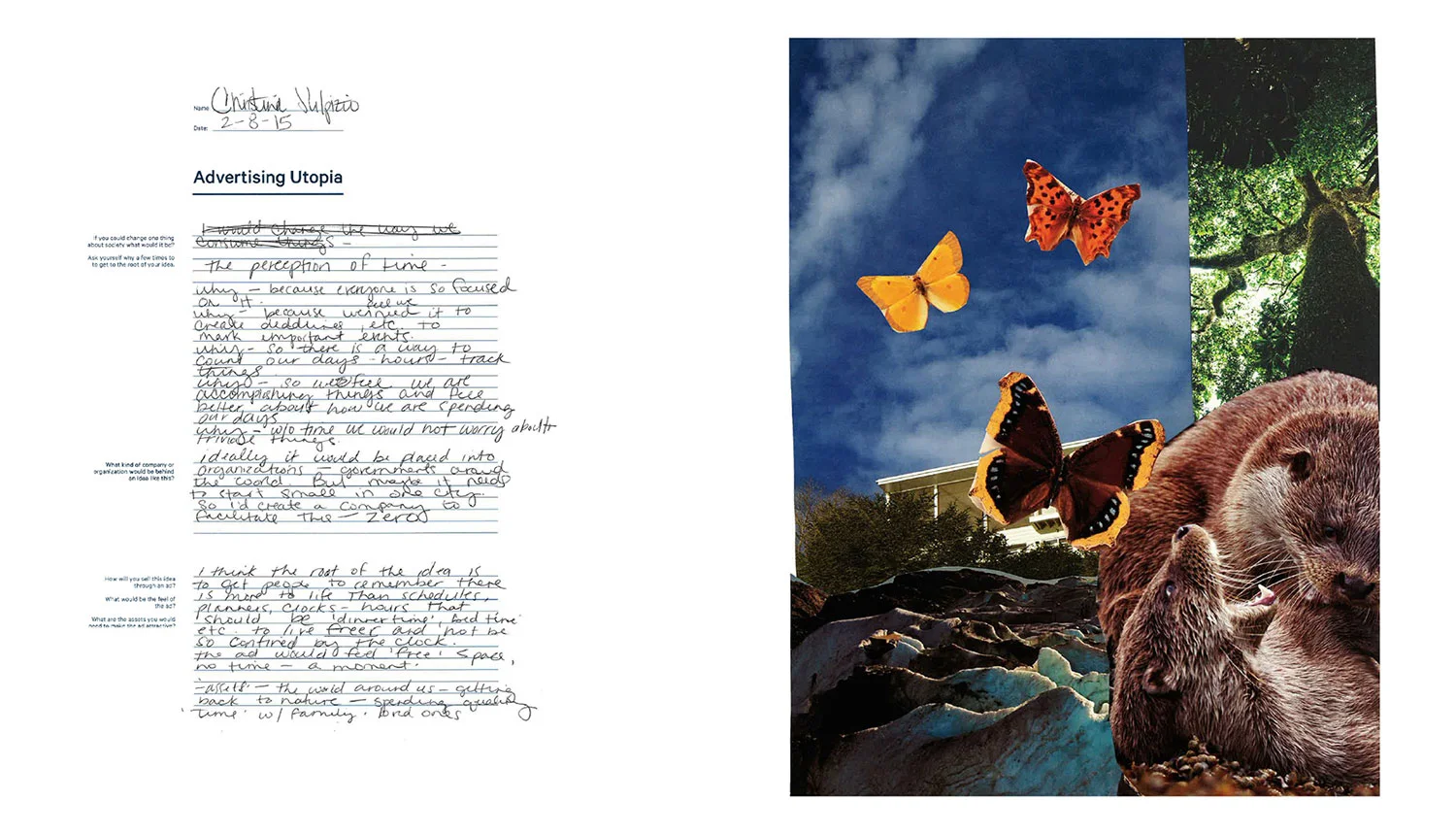

Brandon dovetailed this technique into a co-creative workshop as a way to tap into people’s ideal worlds, and to express them through a print advertisement.

The participants were given a worksheet with the following questions: What one thing would you change in the world? Why would you change it? What company would be most likely to pursue this change? And what would this idea look like as an advertisement? The worksheet ultimately acted as a brief for them to construct their ad—looking through and tearing out images from an array of magazines for material.

The workshop manifested a lot of great pieces. One in particular was a participant expressing the need to create more time to explore nature, instead of focusing all of our time at work. Here it is below:

During the workshop, participants created a “mission statement.” Mission statements are typically used by companies to keep employees and their ideas complementary, to stay on course with common goals, and to measure initiatives against. A manifesto can be a similar thing. Manifestos have been used widely throughout history—from the bible to Martin Luther King to the Dada Movement.

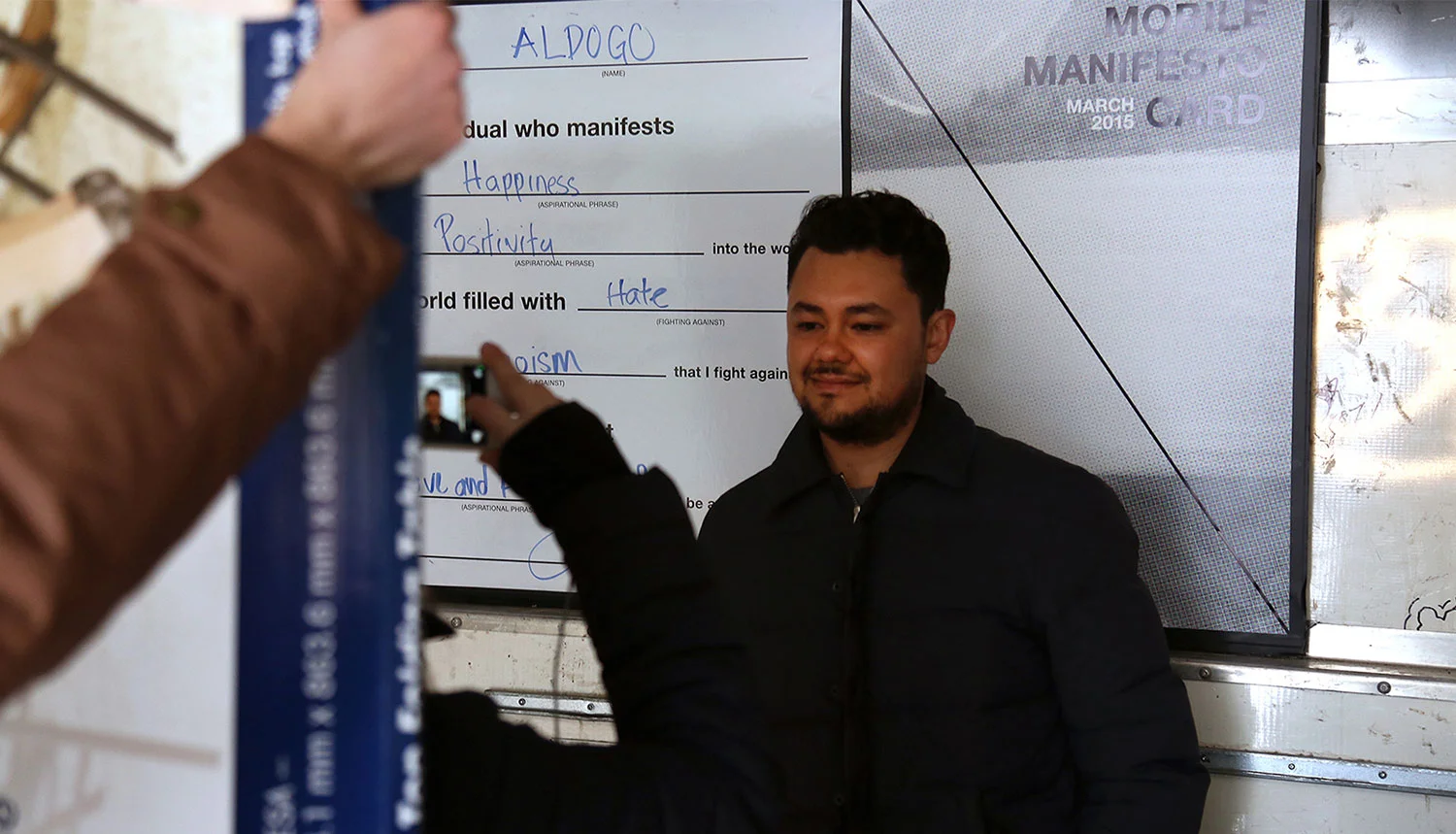

Mobile Manifesto is a traveling intervention, where participants craft a manifesto and walk away with an ID card that expresses their beliefs.

Mobile Manifesto

In the next phase of the thesis, Brandon took the concept of a manifesto and turned it into an experience. He argues “in our fast-paced society, we leave little time to understand what we truly desire for our short, precious lives. Manifestos can uncover what we most want, and can become a roadmap for how to get there.” Mobile Manifesto is a traveling intervention, where participants craft a manifesto and walk away with an ID card that expresses their beliefs. “It’s is an experience to give people a permanent reminder of what they really stand for in this spectacle world,” he adds.

The manifesto takes form of an ID Card, so that it can be kept it in a wallet, close at all times. The hope is that it serves as a reminder—a physical piece of evidence—that people are in command of their true desires, despite the outside influences bombarding them every single day.

To keep the event mobile, Mobile Manifesto took place inside a truck. On the interior wall of the truck is a “Manifesto Mad Lib” on an oversized ID card. Participants chose inspiring words generated from aspirational manifestos and mission statements. Armed with a laptop, a smartphone, a printer, and a laminator, Brandon and his team were able to snap a picture in front of the giant ID card, and print it out on the spot.

Brandon was surprised and intrigued to see how much time people spent creating their manifestos. “I was proud to see that they took declaring their desires and intentions so seriously,” he remarked. “People would erase and rewrite, erase, rewrite, ask a friend what they thought, have a deeper conversation about it, and then write it out again.” A total of thirty-five people manifested with an ID card, but Brandon wondered how he might be able to scale the activity.

Manifest

Here Brandon created a web app that turns your manifesto into a digital poster. Manifest helps users create a manifesto using the five why’s method mentioned above—creating an interactive, digital poster.

First, users are presented with a prompt to start them off. Using the five whys method, the manifesto becomes richer in meaning and deeper in expression. Manifest takes the user’s statements and searches the web for content that reflects the user’s manifesto. The platform tries to utilize all types of media, offering up videos, photos, audio, and articles that might contribute to the work.

The Manifest platform puts all the content together, creating a mood board-like page that makes the manifesto visually engaging. The digital poster is massive and non-linear, welcoming a bit of randomness and inviting discovery.

In a Frontline television documentary, author and cultural critic Douglas Rushkoff calls our new generation “Generation Like”—re-framing “likes” as a currency that empowers the individual. “Young people want validation and attention,” Brandon adds, “and social media makes it easy for them to get it.” And of course, companies see this as an opportunity where social media users push their products for free. Their audience becomes their sales force—selling their products for them.

The “like” button is the actuator and sensor of social media. We can quantify the “like.” It is a mark of viewership, a sign of validation, a digital equivalent of a gold star. Manifest as a social media site attempts to counter this by eliminating the like button. It is used solely as a platform for expressing oneself to others. Your profile is the main interaction, and the site encourages people to return and update it.

Brandon reminds us “that the spectacle is a communication tool that employs fantasy to sell you shit. It all boils down to us being persuaded to spend money we don’t have, on things we don’t need, to create impressions on people we don’t care about.” And in the thesis work, he encourages us to live our lives, instead of watching them.

See more of Brandon’s thesis work as it unfolds on his thesis blog meandmythesis.tumblr.com and his other work on brandoffwashington.com. Email him at bw[at]brandoffwashington[dot]com.