MASTERS THESIS: Uplift: Happiness & Communication in the Context of Cancer, by Berk Ilhan

Products of Design MFA graduate Berk Ilhan’s thesis, Uplift, addresses the quality of life of cancer patients—identifying opportunities that cultivate joy and happiness, and strengthening the support group around the patient. Since Berk’s diagnosis of asthma as a teen, hospital visits became more and more routine—leading to his developed interest in creating better healthcare products and services. Based on his hypothesis that through design, joy and humor can positively change most experiences—and inspired by the revolutionary physician Hunter Doherty (popularly known as “Patch Adams”), advocate of humor, fun, and love in healthcare—Berk’s initial research was about re-imagining hospital experiences beyond conventional boundaries. Berk investigated how design could touch people at an emotional level, especially in situations where they feel most vulnerable. He asked, “How could products change the dialog between patients and doctors?”

Berk asked, “How could products change the dialog between patients and doctors?”

Speculative Design: Squashy Syringe, Emotion Necklace, and Dare

Berk’s initial design-led research included several provocative speculative design concepts. Squashy Syringe reimagines the often-terrifying experience of receiving a needle injection. “What if the syringe wasn't so scary looking?” he proposed, and designed an apparatus that hides the needle under a smooth and harmless-looking shield.

In order to help patients, doctors and hospital staff better understand one another. Emotion Necklace lets them communicate by visually (versus verbally) expressing how they feel. Using a color-coded system, patients and providers can use non-verbal language to keep from feeling awkward or embarrassed. Each color translates to a certain feeling—such as anxious, angry, grateful, tired, or confused. The concept emphasizes the importance of empathy in the context of healthcare.

Dare is a blood drawing concept that questions the hierarchy between patients and doctors. By turning the scenario into a double-sided, reciprocal action—where the patient draws the doctor’s blood as the doctor draws the patient’s blood—Dare aims to empower patients.

These speculative designs were helpful in provoking thoughts and reactions while Berk conducted his primary and secondary research, aimed at trying to understand the complex problems that cancer survivors, family caregivers, and doctors face. (Research consisted of literature research, conversational interviews, field research, method acting as design research, user journeys, happiness and communication surveys, and co-creative design.) Based on his findings, Berk identified the two biggest factors that can positively affect a cancer patient’s experience: Morale, and Social Support. To address these two factors, he created products, design interventions, service designs and experience designs.

Based on his findings, Berk identified the two biggest factors that can positively affect a cancer patient’s experience: Morale, and Social Support.

The Power of Laughter

Scientific research supports the theory that laughter can decrease stress, boost immune systems, and increase natural killer cells. Focused on improving patient morale, Berk imagined a “laughter therapy” device in collaboration with Philips Healthcare, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and Jimmy Kimmel.

Laughter Box

To test the approach, Berk used the low-cost Google Cardboard viewer—outfitted with a regular cellphone loaded with humorous YouTube videos to create a prototype. He collaborated with a nearby physical therapy clinic, testing the “laughter box” prototype with patients over the course of 6 weeks. Where the average happiness scores of patients was around 41%, the patients who watched joyous videos while waiting for their appointments were approximately 98%—an impressive increase of 57%.

The facial feedback hypothesis posits that our facial expressions affect how we feel. Indeed, if we flex our facial muscles to smile, our brains think that something good happened, results in us feeling happiness.

Smile Mirror

Another product Berk created is called Smile Mirror. One cancer survivor Berk interviewed told him that in the first days since her initial diagnosis, “it was weird to look at myself and acknowledge that I had cancer in my body.” These words inspired Berk to create a playful mirror that allows you see yourself...only when you smile.

By employing a smart material and prototyping the interaction using Arduino, Berk tested a working prototype to observe user reaction.

Smart Smile System

Another research discovery of Berk’s—and perhaps intuitively persuasive—is the fact that smiling actually makes us happy. According to the “facial feedback hypothesis,” our facial expressions affect how we feel. Indeed, if we flex our facial muscles to smile, our brains think that something good happened, results in us feeling happiness. Arguing that as a result, "we should smile more!", Berk created the conceptual Smart Smile System. Through a series of investigative trials, the final form was born: a mountable smile detector that functions as a "start button" for daily household appliances.

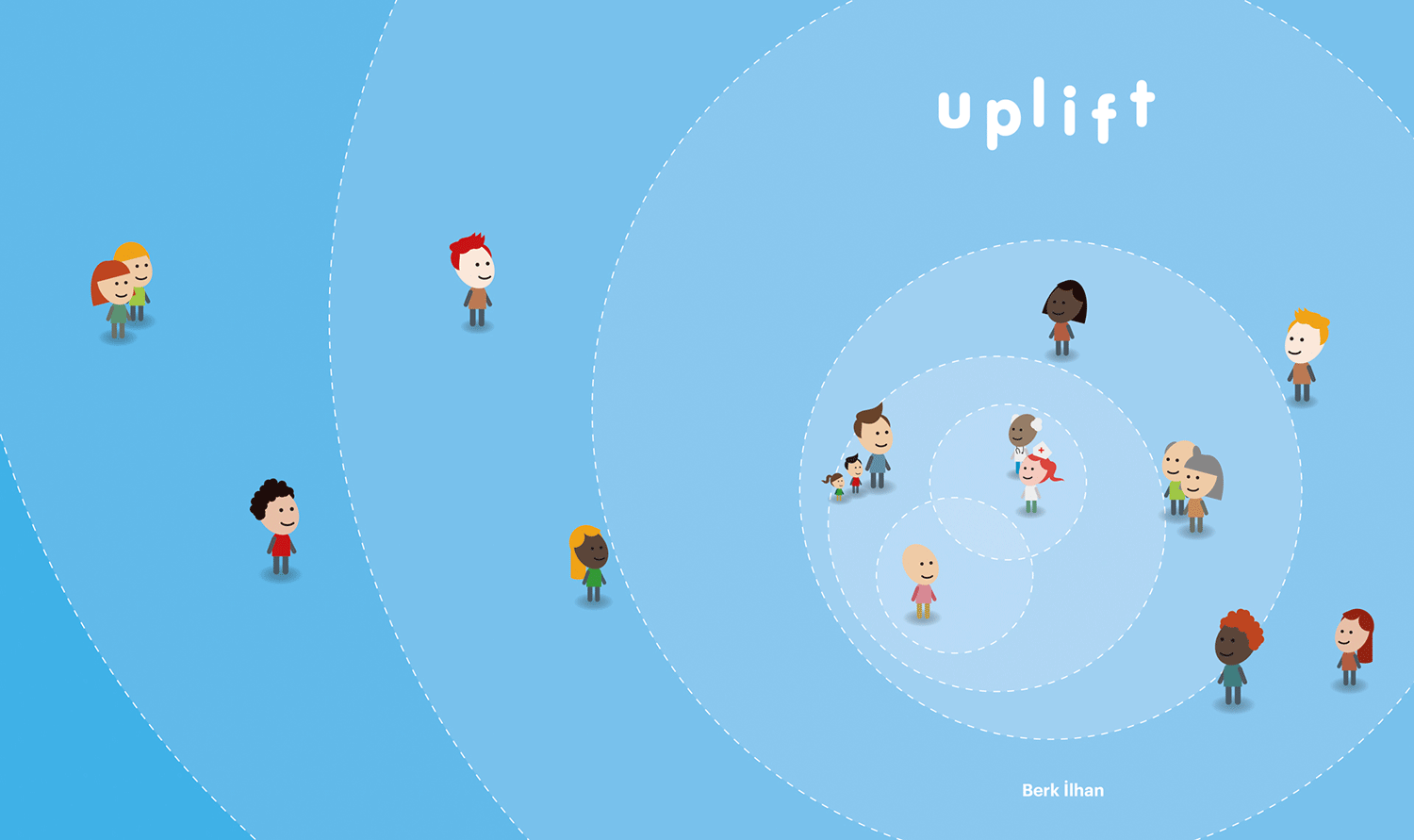

Social Support: The All Together App and Platform

Beyond improving morale, the second important factor that can positively change the cancer patient’s experience is social support. According to the American Cancer Society, 1-in-4 people with cancer face clinical depression, and not being able to ask for help from family and friends is one of the biggest reasons. Berk investigated the factors surrounding this issue, and conducted a survey with 208 participants—including cancer patients, family caregivers, friends and family. Results revealed that 1-in-3 cancer patients didn’t ask for help with daily activities—although they needed that help. And, in fact, 1-in-2 patients said that performing daily activities such as cooking, going to the pharmacy, and grocery shopping were extremely difficult for them. Admitting that the need for help was found to be problematic for patients, as they “did not want to burden caregivers”—especially their family members. Berk felt that he could create a service platform to create a kind of connective tissue between these various stakeholders, and took initial inspiration from the wedding gift registry.

The insight was that the current social contract of "asking for help" is not liberating for patients. The All Together app is an easier way to ask for that help.

Since most people carry a mobile phone, Berk chose to design All Together, a mobile app that allows patients to share their tasks with their friends and family. In effect, “All Together is an easier way to ask for help.” Both “warrior” (patient) and friends/family download the app and sign onto the platform. The patient creates daily tasks to share, adding personal notes and setting deadlines. Friends and family can see active tasks on their calendars, responding when they feel most helpful. (Both mobile phone and watch apps are location-aware; when a task matches up with the location of the helper—say picking up a prescription when the helper is near the pharmacy—the device will receive a notification from the platform.) Both the warrior and the helper can track the task activities, and the service helps to expand the patient’s support group by activating a larger social network through a common goal.

Experience Design: Giggle Up

Giggle Up is a design performance and interactive experience that explores the idea of spreading contagious laughter. The event took place on March 28th, 2015, in the Flatiron District of New York City. Three actors dressed in white Tyvek suits carried wooden frames equipped with on/off toggle switches and LED indicators. The conspicuous outfits and equipment attracted curiosity, and many people stopped and watched the show with delight. As the audience became more engaged with the actors and began to engage with the switches—the actors laughed loud when “triggered”—the audience began to laugh. As a takeaway, people who participated were given paper stickers—providing them with a no-tech "giggle up" button. Spontaneously, they then started to play the game with each other, pushing each other’s buttons and laughing along the way. The device worked to great effect.

In the end, the Uplift project aims to help improve the quality of life of cancer patients and caregivers by using design to provide new tools and services that support them—both emotionally and socially. Most of the concepts created in the thesis can be used by a variety of people suffering from a wide range of conditions—from chronic to life-threatening—but can also aid in the everyday context of a hospital visit. It is Berk’s hope that these projects will continue to evolve and find their way into multiple contexts.

See more of Berk’s work at berkilhan.com and email him at berk[at]berkilhan[dot]com. Also, check out Berk’s thesis blog to read more about the project.