Masters Thesis: Whateverest: Exploring the Landscape of Apathy and Agency, by Charlotta Hellichius

Charlotta Hellichius’ thesis, “Whateverest,” investigates the landscape of apathy and agency. She positioned it as an exploration into her own shortcomings, and an attempt to understand why she “can’t care about everything.” Charlotta set out to understand and explain why certain behaviors are integral, while others fail to become equally as important. Whateverest is about how to overcome the “whatevers” that we face in our everyday lives, and explores the landscape of apathy, harnessing personal agency, and designing for our cognitive limits of engagement.

Every day we face an avalanche of choices that we have to “deal with”—what to wear, what coffee to order, what to prioritize at work, what lunch to eat, what YouTube video to watch, what email to respond to right now, and which ones to save for later. This affliction is called “decision overload,” and all of these small decisions are taxing our capacity to focus.

Interruptions in workflow cost U.S. companies over 650 billion dollars per year. The dogma of Western society states that freedom equals happiness, but this may not be necessarily true. In his seminal book, The Paradox of Choice, Barry Schwartz argues that more choices and more freedom may actually translate into more perceived lost opportunities, more disappointment, and more self-blame.

Apathetic behavior may be a survival tactic; cognitive capacity is a finite resource, and instead of feeling liberated by all our freedoms, the lack of limitations may create a kind of paralysis. More freedom may actually equal more unhappiness.

Charlotta’s initial explorations created a commentary on how this choice overload problem is reinforcing apathetic behavior. She asks, “When we can’t see the impact our behaviors have on the world, how do we know that they make a difference? This lack of feedback—from large to small—is reinforcing our apathetic behavior. There needs to be more opportunity to connect large-scale issues to small-scale changes. We can’t climb all these mountains at the same time, but if we can choose to be selectively engaged, we can start to connect the issue of overfishing, for example, with the tuna sandwich I had for lunch.

“The small decisions are the most powerful moments where agency can make an impact. You can’t change global warming, but you can change lunch, and you implementing a change is dependent on you thinking that you can succeed at it.” According to self-efficacy principles, this can be done by moving away from being motivated by external factors towards being driven by internal motivation.

Research suggests that this can be done by acknowledging choice overload as an issue in itself, and choosing not to choose everything. “We live in a world that makes us scattered and divergent multi-taskers, overwhelmed by choices in a constructed environment,” she adds. “Choosing what to choose can sometimes feel like a mountain of a task in itself!”

Charlotta looked at how our community currently inspires habitual changes, and concluded that it is largely done through negativity. She explains: “Don’t do this, don’t do that, don’t eat that, don’t smoke or you will die. It’s not working because you can’t stop a habit without interchanging it with something else. By focusing on what we shouldn’t do, we do not have enough willpower and cognitive capacity left to focus on what we should be doing. This negative tone creates a negative spiral. People are told what not to do, they focus on not doing it, they tend to fail, and as a result they lose a sense of self-efficacy, which means that they lose belief in their ability to succeed at doing anything at all. This in turn creates a gap between what we expect of ourselves, and the harsh reality of not being able to fulfill those expectations.”

Charlotta she set out to design a strategic framework in which people could take part—implementing a way for people to experience small successes in their everyday lives. Research reveled that the most effective way of creating a strong sense of agency is through “mastery experiences,” where successes build a robust belief in one’s personal efficacy. These small successes are achieved through the implementation of tiny habits. Tiny habits are the minimal viable option of changing a behavior. By starting small and building up, people have a greater chance of implementing change. And design can help people succeed at these small changes by instantiating these self-efficacy principles into products and other design offerings. “If design can assist people with what to focus on and how, they’d be set up to ‘win’—increasing their sense of self-efficacy and empowering them to make additional, larger changes. The spiral of negativity would transform into a pattern of positive reinforcement,” Charlotta argues.

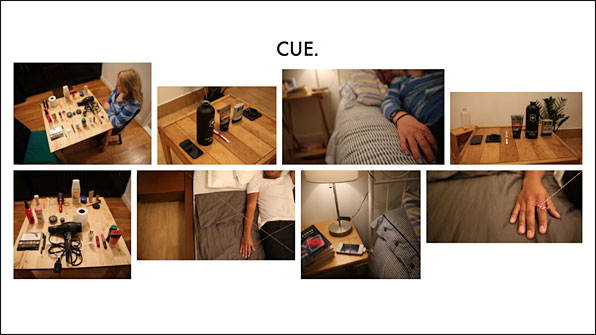

Habits have three building blocks: Cue, indicating that you should do something; Change, the actual behavior; and Reward, the gratification of completion. Charlotta’s subsequent work explored these different aspects of habitual behavior, toggling between objects, embodiments, and curricula that each explored how to create rewards for positive habits that are not yet intrinsically engrained. A framework was created that allowed for people working and living in close proximity to divide a goal, take ownership of a part, implement it as a personal habit, and collectively celebrate successes.

The result is Summit—a platform to help people combine the factors of cue, change, and reward—by strengthening their agency and developing habits within a social context. At its heart, Summit is a service that makes connections between the seemingly unattainable and the factual and actionable—helping participants follow through on their promises by connecting them to others who share the same goal.

Charlotta employed the metaphor of ‘mountain climbing’ and creation the of ‘an expedition’—harnessing a community to embark on a journey with shared responsibility, burden, and celebration around positive habit formation.

At sign-up, users onboard through an interface that asks them to define current behaviors, decide on a future, large-scale goal, and then suggests small, crowd-sourced, daily habits to lead them there. After choosing the small behavior, members are presented with a realistic timeframe and asked to define a strategy to integrate the new small thing into an existing routine. The Summit platform then presents crowd–sourced options for behavioral cues, linking new, tiny habits to an already existing one. And given the importance of social support in habit formation, members are then introduced to the Summit community where they can choose to create an expedition of their own, or to be grouped with peers that share the same goals and cues.

This is accomplished through a text message chain: Users joining an expedition start off as “the mentee” at the end of a text chain. After the successful completion of a new habit, members move up through the text chain: The better you are at keeping yourself on track, the more people you get to take responsibility over by reminding them to do their own tiny habits. The initial interaction with Summit is on the web platform, but following interactions are personal and text message-based.

“Summit has been a tool for me to examine and define the role design can have in teaching behavior change,” asserts Charlotta. “Setting goals and reaching them is a skill that can be learned, and in the end can make people happier by bolstering their sense of self.”

Moving forward, Charlotta is working in the social innovation sphere and looks back on her thesis process as a wonderful, exploratory learning experience into her own behavior, as well as into behavior of others.

See more of Charlotta’s work at hellichius.com, and email her at charlotte[at]hellichius[dot]com.