POWER PLAY: Designing for Agency and Empathy in Virtual Environments

In her thesis Power Play: Designing for Agency and Empathy in Virtual Environments, Phuong Anh Nguyen examines how human cognition and behavior change when we socialize in the virtual space. This quickly-developing technology provides contents so detailed and believable that users can feel full immersion and their own physical “presence” in VR. On the flip side, traumatic experiences like sexual harassment also feel absolutely visceral.

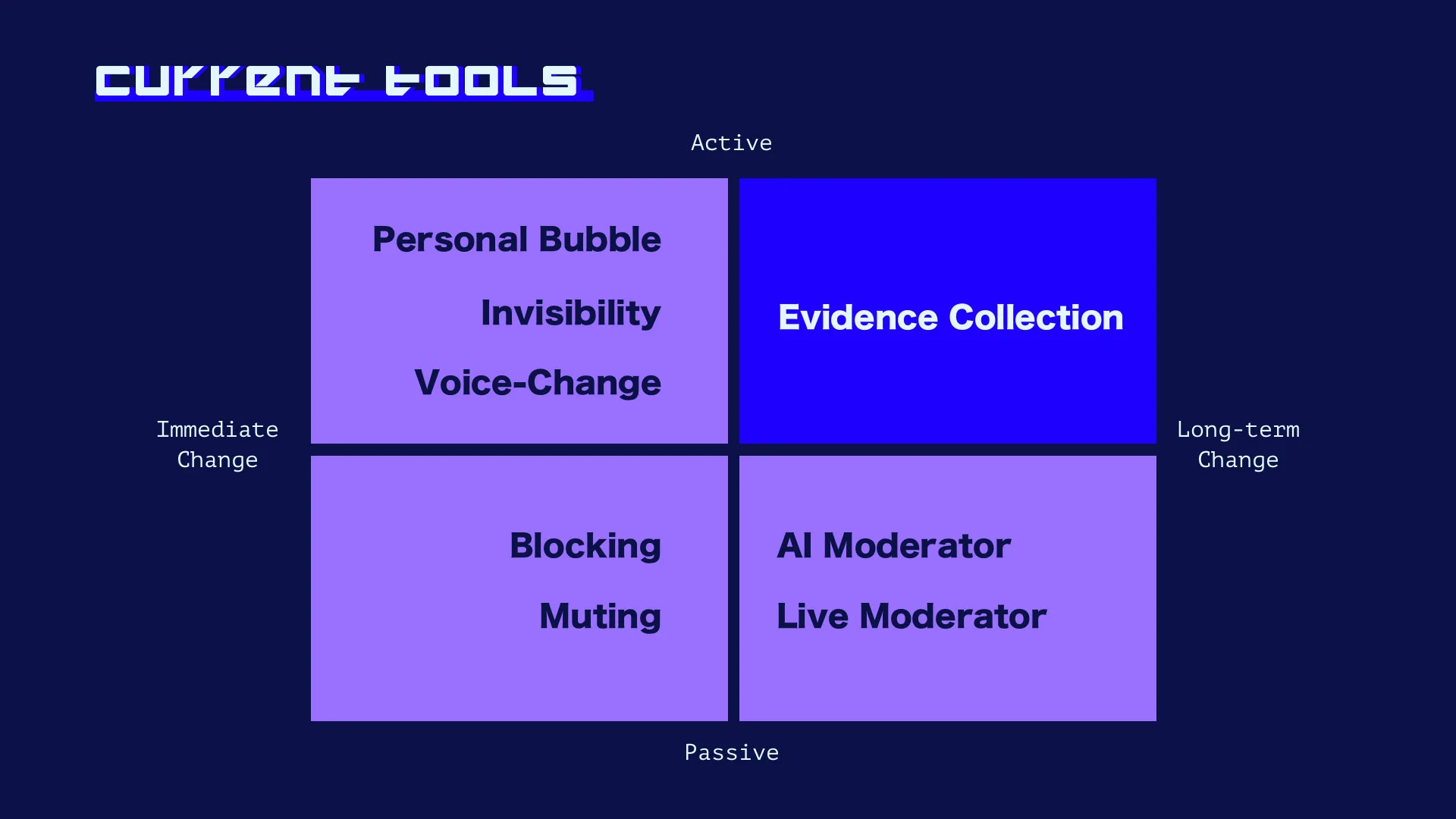

“While this blurry space may be new for society, the ethical concerns and how we navigate them as a collective are as pressing as ever,” says Phuong Anh. As it does in the physical world, violence against others occurs in VR spaces. While designers may not be able to expunge this from human nature, Phuong Anh believes that we can design tools for victims to gain agency over their harasser. “More importantly, we can now introduce empathy-building products and experiences to shape respectful behaviors in current and future virtual environments,” she adds.

CHEK

For many Americans, harassment is a normalized feature of life online. According to a 2017 survey by Pew Research Center, women, especially young women (18-25), are twice as likely to receive sexualized forms of online abuse than men of the same age. A 2018 survey by the AR/VR/MR research agency The Extended Mind revealed that close to half of the VR users who are female experienced sexual harassment in VR. One user said, “A man noticed my black female avatar and started asking me for a date… followed by making a humping gesture.”

“With the sense of 'presence' in VR, a person can invade your personal space and grope you in a way that you truly feel is real and creates a visceral reaction.” –Renee Gittins, CEO of Stumbling Cat Game Studio

CHEK is a speculative, choker-collared haptic vest that gives reality checks to users of social VR. It functions like other haptic vests, vibrating when there’s an interaction in VR; however, unique to CHEK is a training collar wrapped around the neck, meant to punish misconduct committed in virtual space in real time. The row of nails on the choker serves to replicate the victim’s emotional pain by physically translating that pain onto the harasser. Advertised as a way to play responsibly, CHEK seeks to connect digital misconduct with physical consequences, in hopes of creating empathy and accountability in the harasser, and possibly changing their behavior.

Tueri

Tueri is an in-app tool that facilitates the evidence collection of virtual sexual misconduct, by allowing potential victims to record harassment interactions and report them to platform moderators. The videos Tueri records not only serve as tangible examples of violations of the platform’s code of conduct, but more importantly, provide the accountability users need from social VR platforms. Phuong Anh designed Tueri after learning of the difficulty of determining victim recourse in cases of virtual misconduct, both because of ineffective policies on VR platforms, and deficient support from legal systems. The product name Tueri means “to watch, protect, and preserve” in Latin.

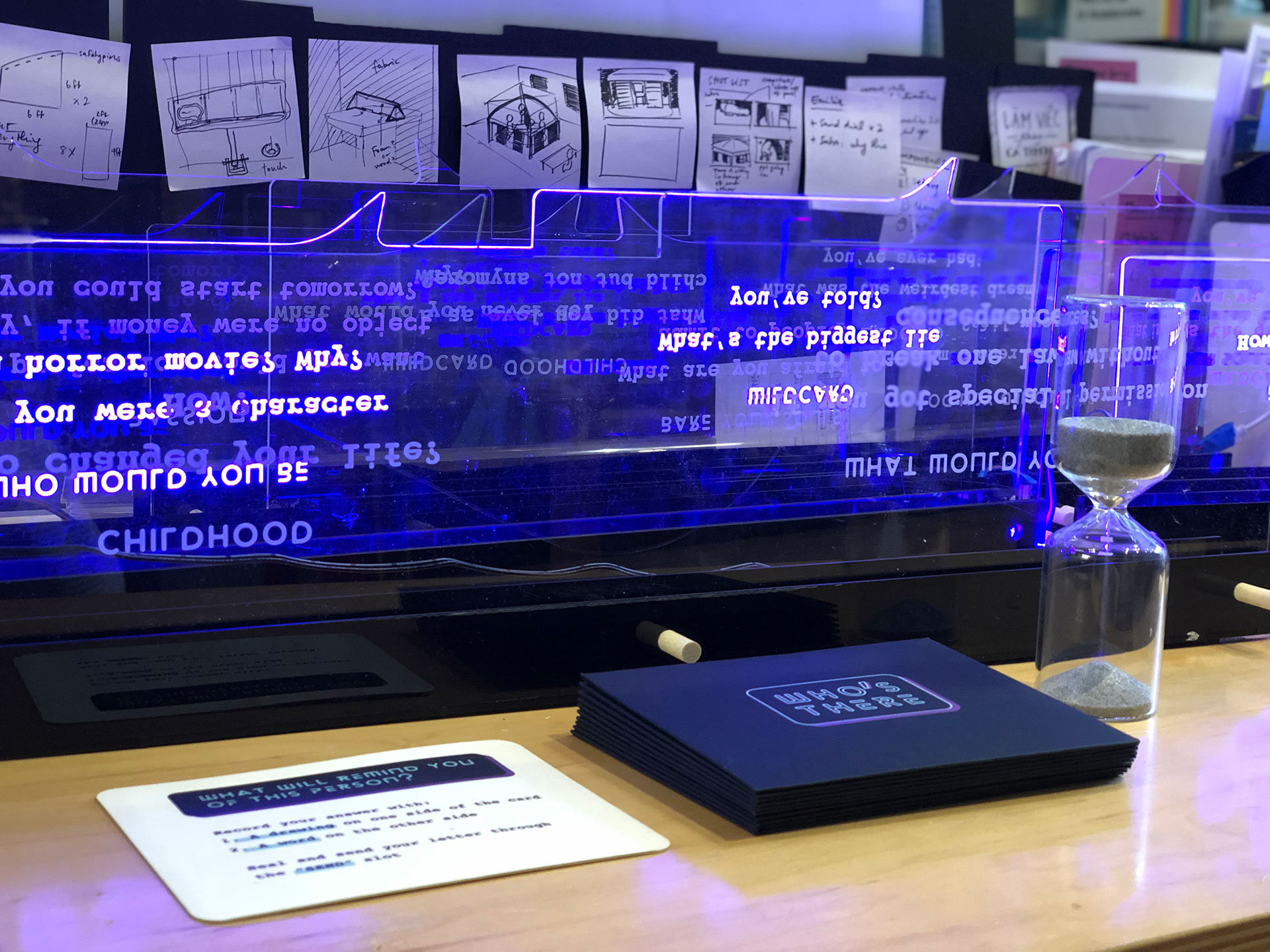

Who’s There

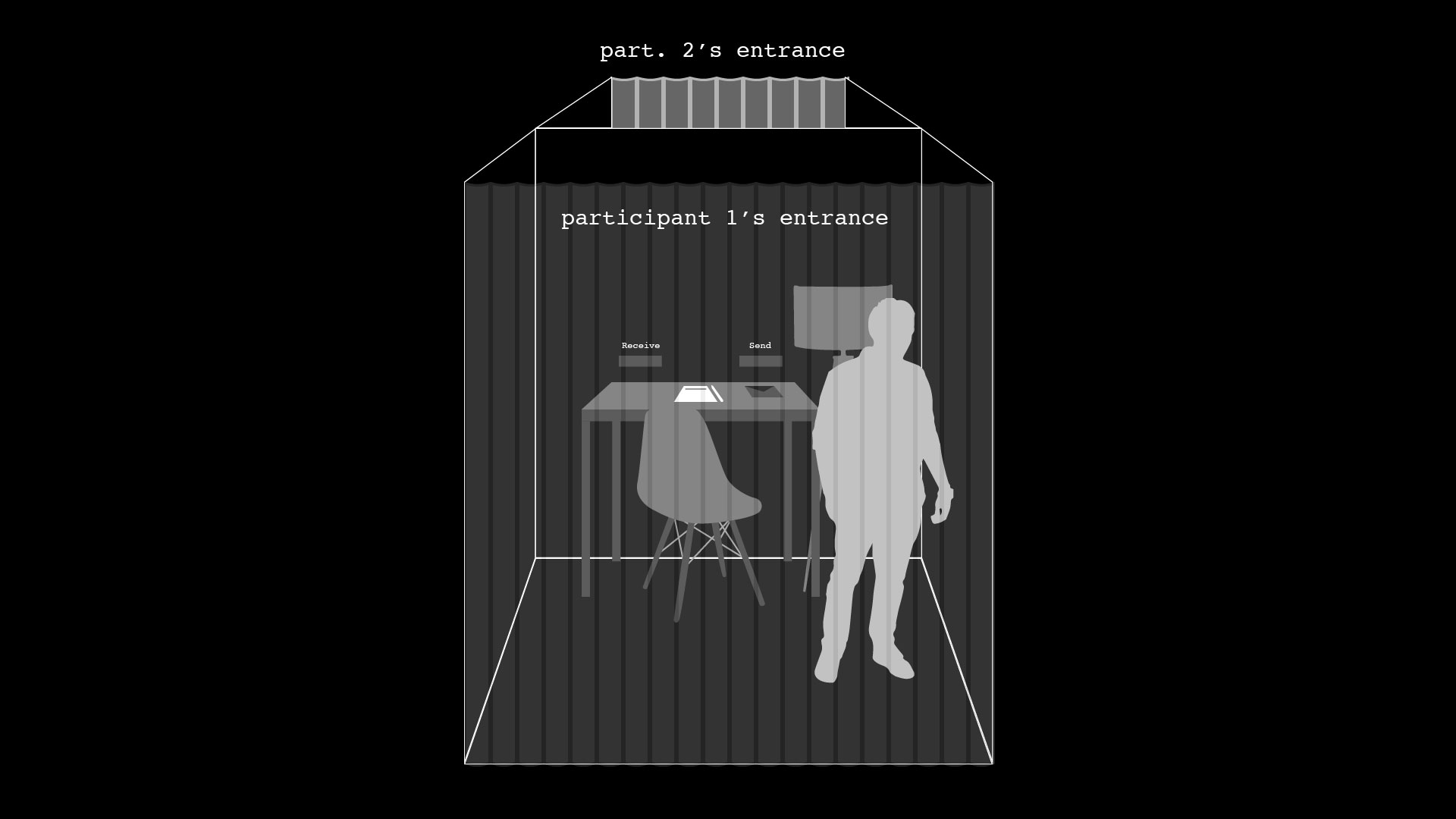

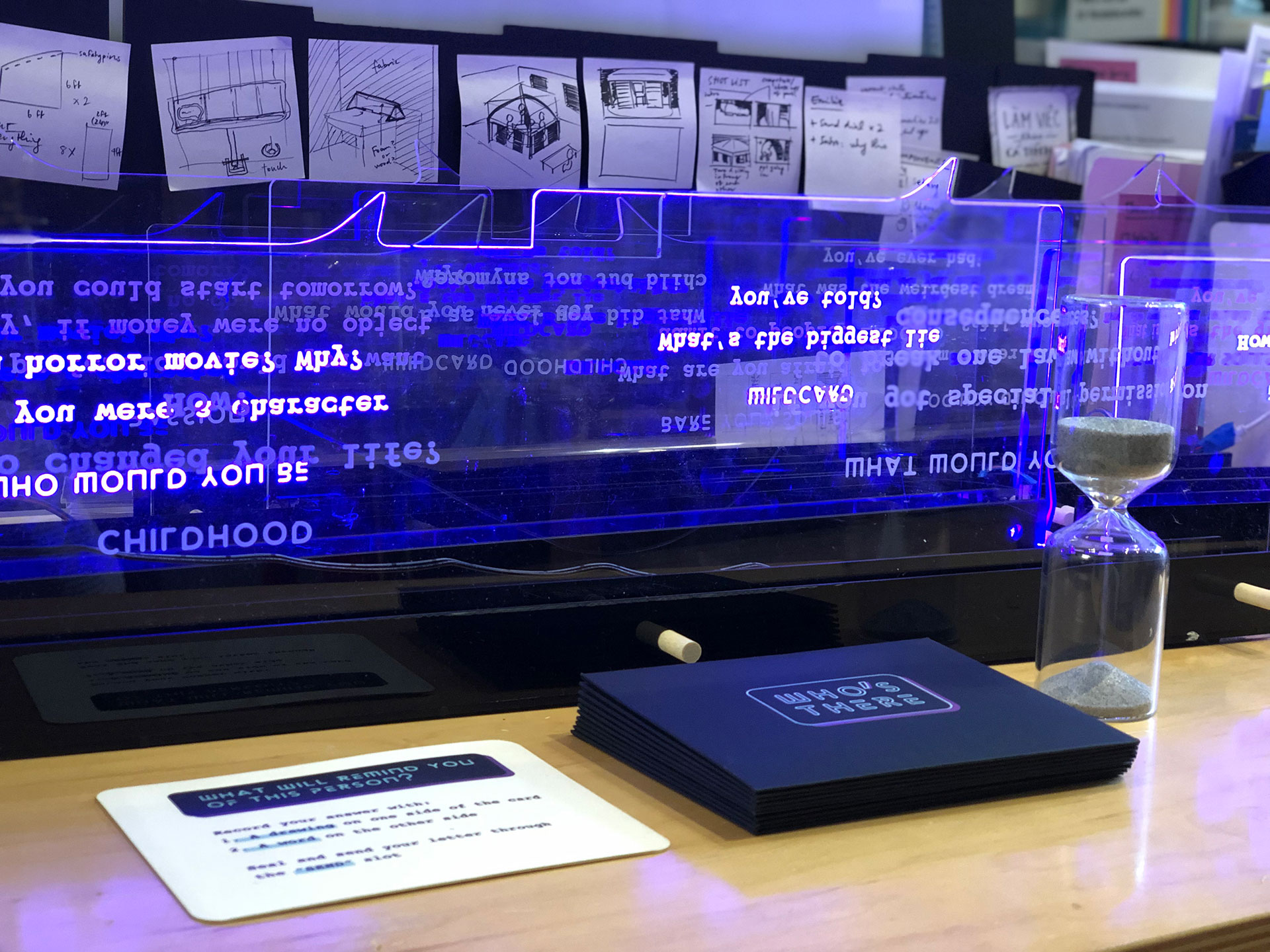

Who’s There is a physical manifestation of a virtual chat room in the form of a private pop-up experience. It encourages strangers to gain empathy by actively listening and sharing their own stories with each other. The experience incorporates anonymity in order to level the playing field between two people, much like what avatars do for users on social VR.

Participants are paired up, and converse through a blackened fabric divider inside a darkened room. The goal of the experience is for participants to gain an understanding of who is sitting behind the divider. Prompts such as “What are you afraid to admit to people?” or “What did you love as a child but not anymore?” are lit up around the participants to help them get started. After their chat session, each person is asked to write a word and draw a picture of what will remind them of the person. Finally, they send the note as a souvenir to the other person through the “SEND” slot on the dividing screen. In this way, participants will not only learn about the other, but also see themselves through the other’s eyes.

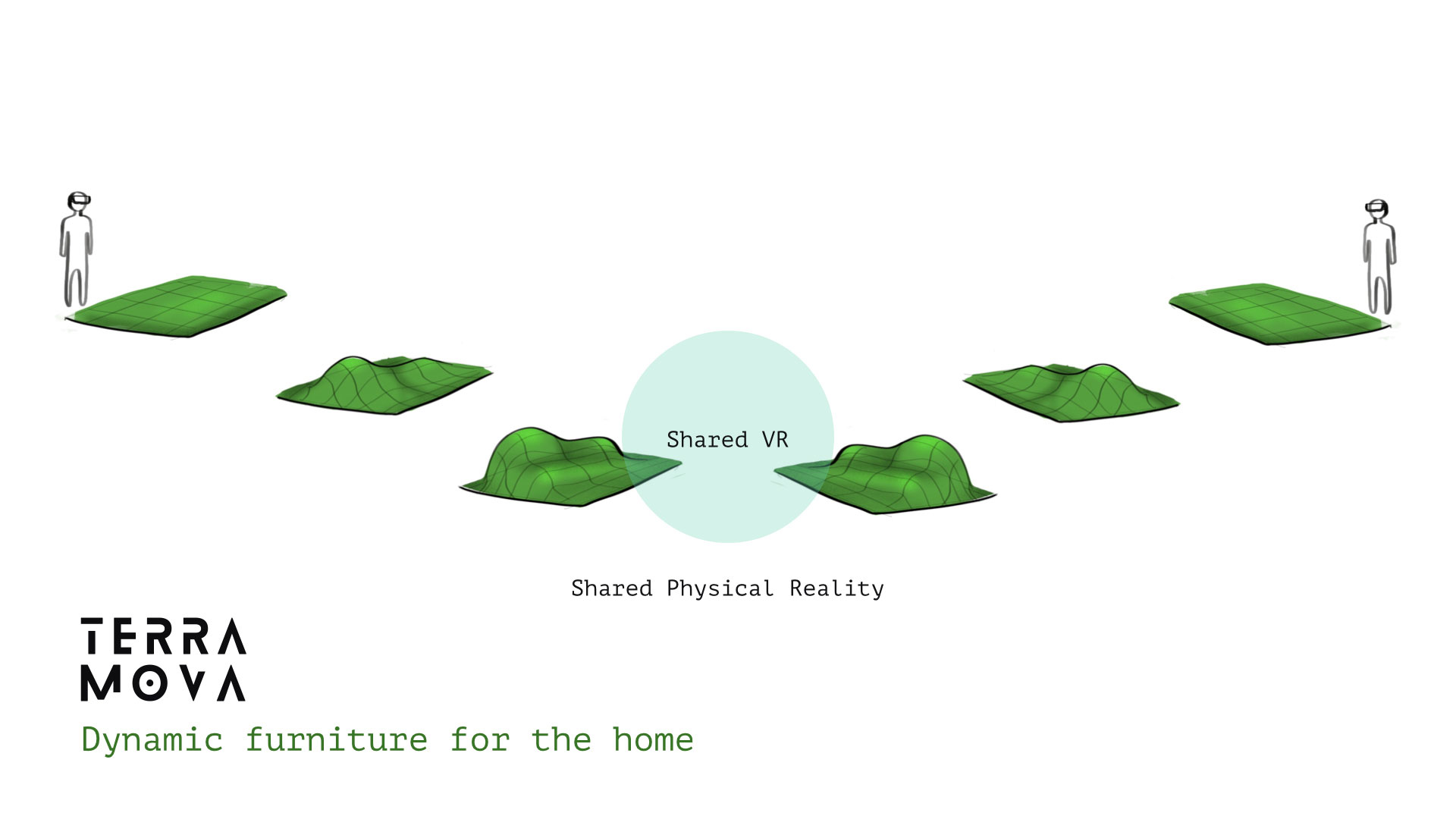

TerraMova

TerraMova is a piece of dynamic furniture for the home that is used as a pair, to bridge the physical gap between two users sharing the same virtual experience. With AI-powered motion and distance sensors, TerraMova reads a VR user’s actions and conforms to the shape they see in VR. In this way, a physical facsimile of a digital environment engages the user further, and allows for a closer connection with their friend in VR.

To learn more about Phuong Anh Nguyen’s work, take a look at her projects in more detail at www.anhngp.com, or send her a note at anhngp@gmail.com.