HEREAFTER: Remapping the Landscape of Death and the Way it is Remembered

Products of Design MFA graduate Panisa Khunprasert’s thesis, Hereafter, uses her role as a designer to create products and services that enable us to externalize grief in an empowering and beautiful way. The world of bereavement—in a contemporary society which does not talk about death or grief—is fertile ground for design. But Panisa's thesis work "doesn’t seek 'solutions' or ways toward closure," she argues. Rather, “it strives to allow grief to be acknowledged and accepted as a normal outlet, and not one to be ashamed of.” She adds, “As a society we have to learn how to live with death and grief, because death is a natural step in life, and grief is the price we pay for love."

Panisa decided to first explore the rituals around death, asking "how have we dealt with the departure of our love ones—historically and across cultures?" She was fortunate to have the opportunity to talk with two leading philosophers and subject matter experts. Mark C. Taylor, Chair of the Department of Religion at Columbia University, has studied and written several books related to death and memorialization. (He also expands his philosophical studies of graveyard cultures into expressive sculptures and photographs.) Panisa expressed her interest in virtual memorialization, and Taylor’s response fundamentally changed her direction: “Virtualization and digitalization brought dematerialization—a shift from stuff to images. From images to codes. And with that in common, delocalization—displacement.”

Panisa’s many design interventions are related to her personal story: Thirteen years ago, a car accident took away the lives of her twin sister and younger brother. It was very difficult for her family, and the event was never talked about at home.

Panisa pursued her inquiry into the materialization and dematerialization of remembrance. Hosting a co-creation workshop entitled “Virtual-Actual Memorialization”, she organized an event for for people of all ages and professions who had encountered death or experienced loss at some some point in their lives.

The workshop was set up around two themes: Future and Past. In the future activity, users were given a visual map of chronology from the present time to the year 2045—“when can reconnect with the dead, and will ourselves be immortal.” From this prompt, participants were asked to create a collage using materials provided as a way visualize and speculate the digital space they would use "to communicate with the consciousness of the dead."

The second prompt took the participants back to the past. Each participant was given a white box—a keepsake box where the past 50 years of memories between the living and the dead were to be kept. Participants would create the contexts for their boxes, imagining how they would use, keep, or interact with the box. From the workshop, Panisa learned that people are indeed very interested in memorialization, and were able to “physicalize” their ideas and projections in a very encouraging way.

She expressed her interest in materiality and her belief in “the tactility of memory” when speaking with John Thackara, world-leading design thinker and author. He told her about animism. “Why does a photograph of a loved one has so much meaning even if it is just a piece of paper?” he offered. “It is not about the artifact itself, but about what we project onto it. It has the power to represent things which are not really there.”

This resonated with Panisa’s own experience, because she would sneak into the storage room in her home in Thailand and spend hours looking through old photo albums of her childhood, honoring the memory by gently handling each image. She would lose track of time and be transported into the world of memory without any distractions. With today’s technology and user behavioral changes, we use Facebook to store our memories. But this platform brings in many distractions—comments or neighboring posts which my frustrate the bereaved.

The Memento-Mori Service

Here, Panisa envisioned the Memento-Mori service—a service which takes the content from the deceased’s Facebook account, physicalizes it, and delivers it to the bereaved’s door. The bereaved user signs up for the service, enters the deceased’s name, and selects important dates to be memorialized. The service will connect to the deceased’s Facebook account and collect content, posts, and photos from those selected dates, print them out on “traditional” photo paper, and nicely package them up in an elegant box. The box will then be delivered to the bereaved on the exact anniversary day of the death of their loved one. The bereaved will find solace in the “un-boxing” and in the nostalgic experience of old discovering photographs that they had forgotten about, or never knew existed.

The intention of Allusion is to offer the bereaved something that they can physically use and maintain—preserving memories they can hold onto during the mourning period.

Allusion Alter

Allusion is a wall of mounting altars that physicalize different stages or ways of grieving—exploring the complexity of grief and expanding its elements into simple, visual representations. The intention of Allusion is to offer the bereaved something that they can physically use and maintain—preserving memories they can hold onto during the mourning period. Users are encouraged to store physical items that are important to them or the deceased, and establish their own symbolic rituals or routines to interact with the alter. Here Panisa offers, “The product symbolically suggests three different things: Deliberate gestures, designated places, and the ephemerality of time.”

The idea of physicalizing and actively performing rituals to grieve is a powerful healing tool. According to the celebrated book, On Grief and Grieving : Finding the Meaning of Grief Through the Five Stages of Loss by Elizabeth Kobler Ross, M.D., and David Kessler, we need rituals or tasks to help occupy our mind during the healing process. “To many, this sense of being busy is a blessing; what else could possibly seem worthy of your time? If we sat and felt the emptiness, it would be too much. We want it done the way we think is best, the way that would be honoring our loved one. We need rituals. We take comfort in the busyness. It is an integral part of the mourning process.” These thoughts inspired Panisa to create Allusion.

Since she had no one to talk with about her feelings, these scars acted as a testimonial to the memories she had shared with her siblings, and as a visible way to remember them.

Panisa’s many design interventions are related to her personal story. Thirteen years ago, a car accident took away the lives of her twin sister and younger brother. It was very difficult for her family, and the event was never talked about at home. Nor did they reach out for any outside help. Panisa was in and out of the hospital for almost a year, and left with scars on her body—“which," she says, "are a constant reminder of the trauma that my family went through, and continues struggling with.” Since she had no one to talk with about her feelings, these scars acted as a testimonial to the memories she had shared with her siblings, and as a visible way to remember them.

Inspired by this experience, Panisa began looking into a form of scaring that people could actively seek, and that would allow them to remember their loved ones: tattooing.

Bloodline Water Tattoos

Amanda Wachob is an artist who uses tattoo machines to create innovative artworks on different canvases. She reflects, “People don’t actively seek out scarification, whereas people actively seek out getting a tattoo. So sometimes in a way I think scars can be beautiful, because it’s like your battle wound. It’s you existing in life, and it’s a mark that came from the real experience.”

Bloodline is a service that offers the bereaved a therapeutic way of liberating their grief, expressing their loss, and preserving memories of their loved ones—through the art of tattooing. The pain created by the needle of the tattoo machine represents the pain of loss, and the art of the tattoo creates the remembrance of love and beauty. But Bloodline is an impermanent tattoo—employing a technique that tattoo artists typically use to create a temporary boundary before coloring—using just water to lubricate the needle. “The marks will fade and disappear in two-to-six weeks,” remarks Panisa, “and as the skin heals, it is time to move forward.” Users can always come back to the service and get another Bloodline tattoo, and then another, she adds, “because grief comes and goes at anytime, and sometimes, you actually don’t want it to stop coming.”

Panisa was also motivated to create work around organ donation because twelve years ago, her own family signed up for organ donation with the Red Cross Society in Thailand. They were looking for a way to both pay tribute to and honor the sudden death of two family members, and to make their own deaths more meaningful. In Thailand, a donation card is given as a reminder of their donation, “and to represent the realization of impermanence and of no attachment to the physicality of your body.”

Conducting research on how the organ donation process works in the United States, Panisa discovered LiveOn NewYork, where she “connected with amazing people, psychiatrists, social workers, coordinators, and organ recipients.” During her research, she discovered the beautiful bond of support among deceased organ donor’s families and recipients: Maria Torres, Director of Donor’s Family Supports & Organ Recipient at LiveOn NY—and who is an organ recipient herself—remarked, “My donor was younger than I was. It took me ten years to write back to my donor family because I didn’t want to bring them back to the time and place of their loss. So for me, it was very difficult.” Maria’s experience demonstrates that our society’s default act toward the bereaved is to be silent. Some donors' families take years to acknowledge the gratitude from the recipients. “When the moment does come and they do connect,” Panisa argued, “the response should be a beautiful moment of transformation.”

Panisa was fortunate to witness such moments at the annual LiveOn NY Remembrance Ceremony & Luncheon. “Some families go on to build strong relationships with the recipients— regardless of race or background,” she discovered. “And the fact that the families see how much their loved one has given helps them to move forward.”

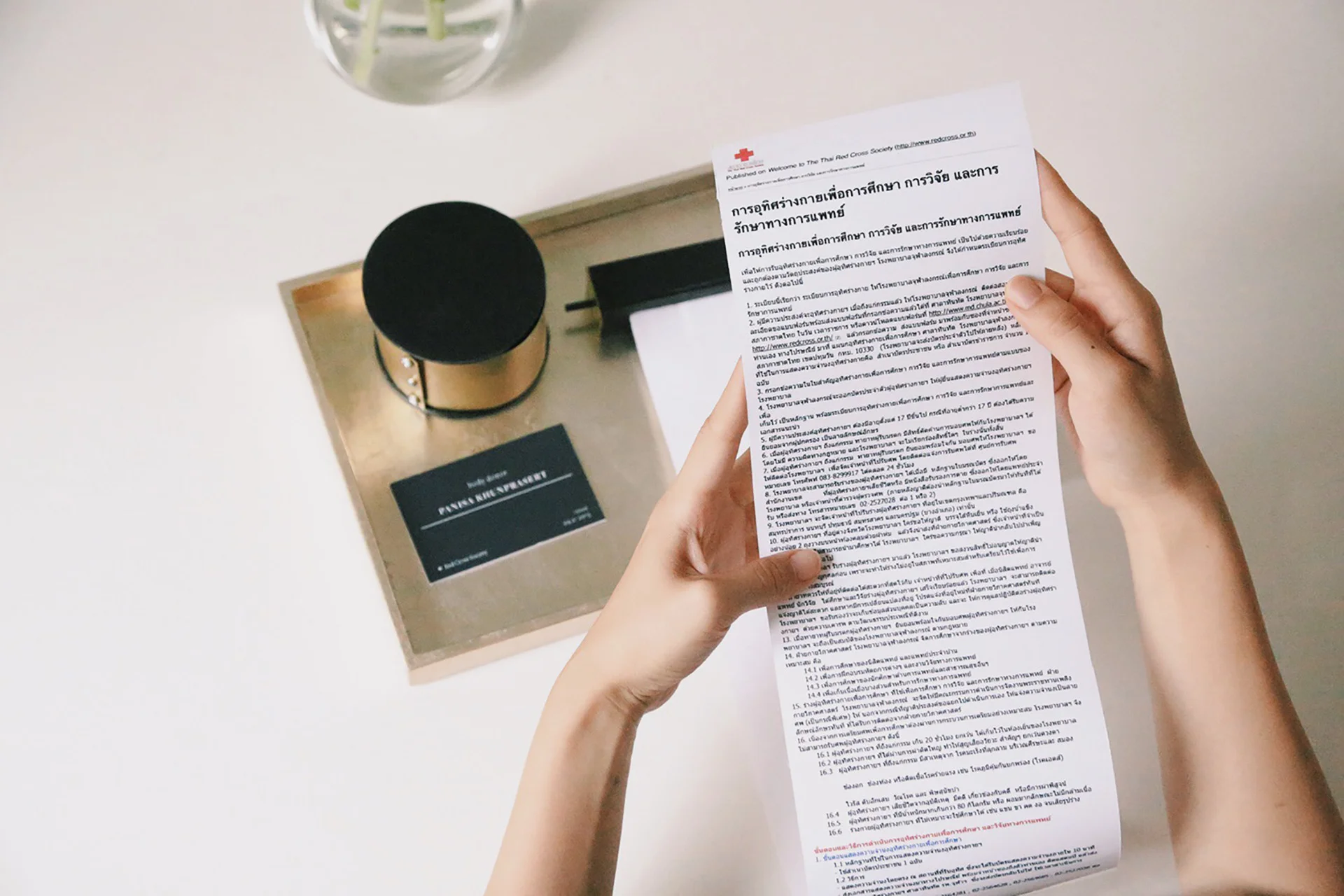

Organ Donation Stationery Set

But for the donor’s family, donation is not always a pleasant experience: They have the task of going through many documents and legal papers during such a sorrowful time, and they may find that making big decisions to be extremely stressful. “They can feel that perhaps they may not be making the best or most rational choices,” Panisa adds.

So she designed the Organ Donation Stationery Set, enabling donors to leave testimonials to their families or future recipients. This speculative item consists of a donor’s card, letter-writing stationery, and documents related to current donation policies. Panisa hopes that the stationery set “can facilitate communication between recipients and donor families, and can help them to connect in a meaningful way.”

The most important lesson she learned was that it takes a lot of courage to state your grief out loud.

Grief and Society

Grief had always been a personal thing for the designer—until she learned that turning to others for help and support, while difficult to do, can be a valuable step in the healing process.

Panisa joined a GoodGrief peer-to-peer support group that helps bereaved families overcome the pain of their loss. She committed to travel to New Jersey every other week to join an hour-long session of “listening, talking...and mostly crying.” The finding from this field study that challenged—even angered—the designer, “is the fact that the world of medicine can prolong life,” but that “grieving is an enemy to a productive society.” She learned that modern society sets a tight frame for grieving, and expects the bereaved to get back to to a normal state as soon as possible.

For example, in the U.S., people are only allowed three days paid leave, according to some state laws. People also do not know how to react around the bereaved. “We tend to avoid them or stay silent—which sometimes causes even more uneasiness to the bereaved,” Panisa says. The most important lesson she learned was that it takes a lot of courage to state your grief out loud. “Sometimes the person who is the easiest to talk to is a stranger, or someone you have met for the first time—maybe because we don’t have any presumptions around their opinions.” That theory was proven when the designer went out on the streets of New York to test the first prototype of The Grieving Wall. Grieving walls exist in many cultures, and use the typology of putting written messages up on, or into, a wall.

Here’s how Panisa's Grieving Wall works: First, the bereaved user receives a package of message cards, along with instructions. They are invited to sit down at the provided tables and chairs, and to articulate their emotions in a written message. They can then enjoy walking in the peaceful garden and thinking about their loved ones. After putting their message up on the wall, they are encouraged to read other people’s messages, and appreciate the collective artwork they have helped create.

After the event, the designer learned that being given the opportunity to express grief and sorrow is a gift to many people. “Because oftentimes,” she adds, “we live with grief, and never realize that a sense of community and empathy can be very helpful.”

Learn more about Panisa Khunprasert’s work at panisakhunprasert.com, and contact her at kh.panisa[at]gmail[dot]com.