This Great Violence: A Thesis on Race

The evening of March 2, 2012 will be remembered by Tahnee Pantig as one of the most violent and intimate evenings of her life. On that evening, she was physically assaulted in front of her home. After the assault, Tahnee was faced with a compelling question. “I asked myself, ‘had I somehow contributed to the conditions where this man felt the need to steal from me?’” This feeling of guilt drove her to use her thesis as a way to reconcile and understand the circumstances which led to the events of that evening, and compelled her to research these themes in her masters thesis, This Great Violence.

“That evening led me to understand that intimacy is not always warm and fuzzy. It can be violent, enforced, even dangerous.”

Tahnee began by referring back to an earlier work she had created in her first year at Products of Design. Scentury is a perfume set that recreates the moment of trauma through the sense of smell. The design of Scentury borrows heavily from one of the most effective treatments for post traumatic stress: exposure therapy. This therapy— traditionally conducted verbally—requires patients to “re-expose” themselves to the thoughts, feelings, and context of their trauma, as a way to reduce the power they have to cause distress. Instead of talking through the traumatic experiences, however, Scentury gives patients a way to desensitize themselves through the aromas of the trauma. Scentury was an early exploration into the violence and intimacy of that evening. Tahnee defines intimacy “as a physical, emotional and mental closeness.” She argues, “That evening led me to understand that intimacy is not always warm and fuzzy. It can be violent, enforced, even dangerous.”

Reading Between The World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates, Tahnee was stunned to read Coates’ descriptions of the experiences of people who are actively oppressed by racism—particularly Black Americans. His descriptions of racism were so similar and so vastly different from her own experience of violence that evening. At one point in the book, Coates points out that racism is “…a visceral experience, that it dislodges brains, blocks airways, rips muscle, extracts organs, cracks bones, breaks teeth.” This description felt so much like Tahnee’s own experience that evening, but was describing an experience so vastly different from hers. She saw clearly then “that violence is intimate.”

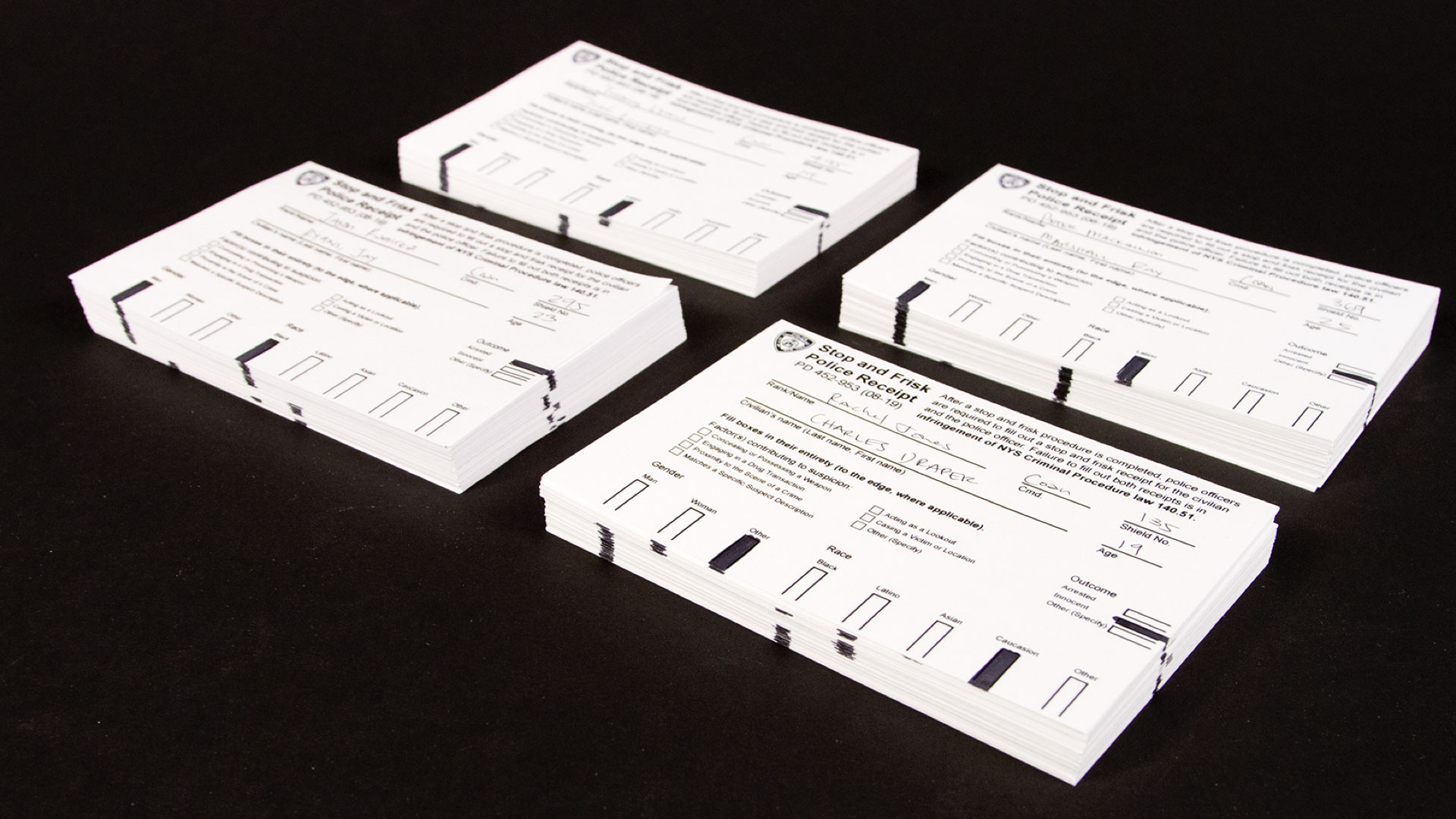

Stop The Frisk

he policy of Stop and Frisk in New York is highly controversial. In 2015, 8 out of 10 stopped and frisked New Yorkers were innocent, and an overwhelming majority of those who were innocent were Black (NYPD Reports, 2015). According to the New York Civil Liberties Union, the policy and practice of stop and frisk has never been proven to reduce crime, and in fact, has been found to corrode trust between the police and local communities. Being stopped and frisked is an intimate and uncomfortable experience. Will E.—a 20-year old Black and Dominican man from Hamilton Heights—described his experience: “…checking other people’s private areas, and people’s rectal area to see if they have drugs in them. It’s just too much, outside—that’s embarrassing.”

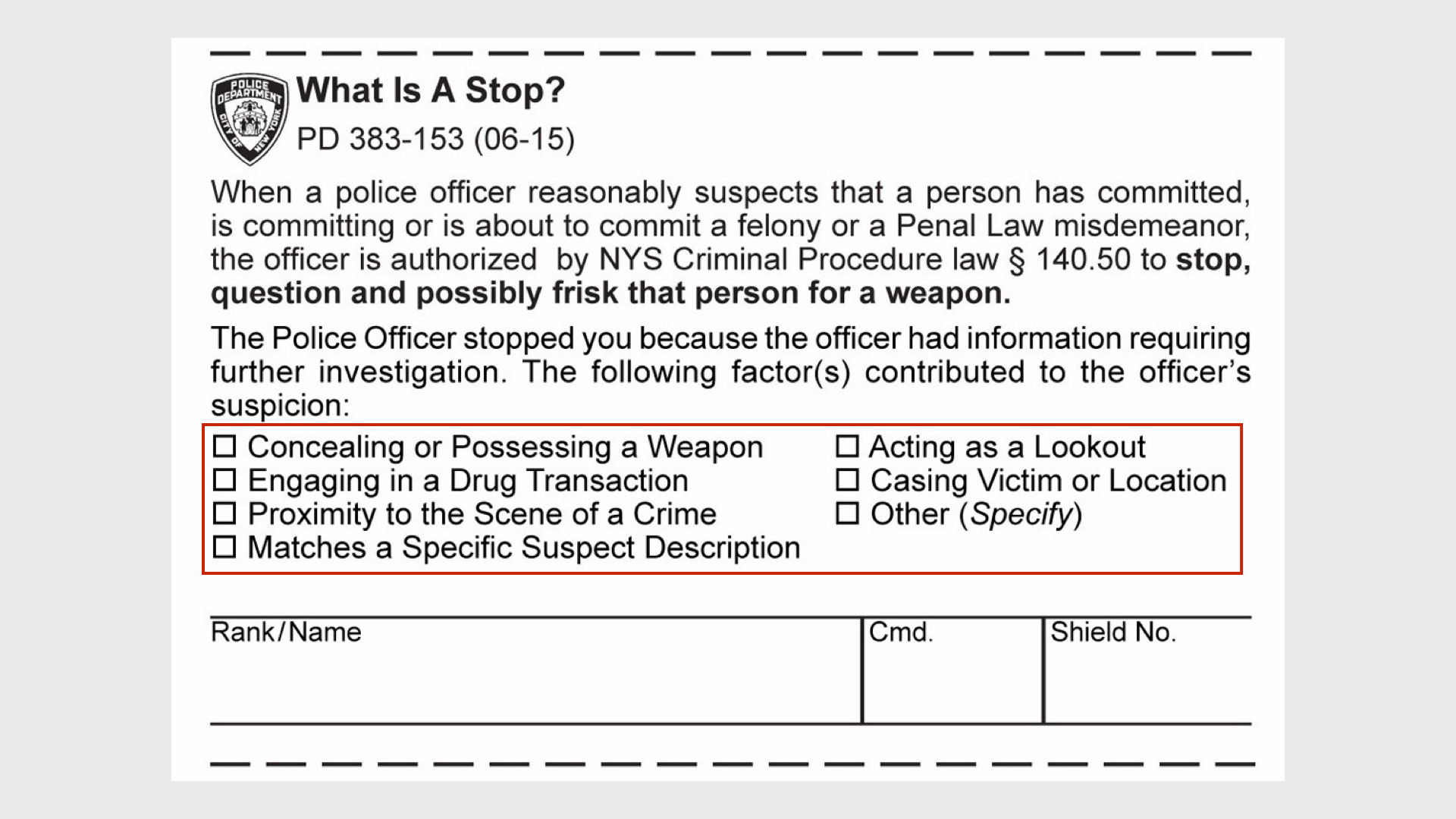

Officers are given “the right to stop and frisk a civilian” under the following grounds: concealing or possessing a weapon, engaging in a drug transaction, proximity to the scene of a crime, matching a specific suspect description, acting as a lookout, casing a victim or location, and at the discretion of the officer. They’re required to give a receipt after conducting a stop and frisk, but this exchange is one sided: The receipt is given to the civilian, but nothing is kept by the officer.

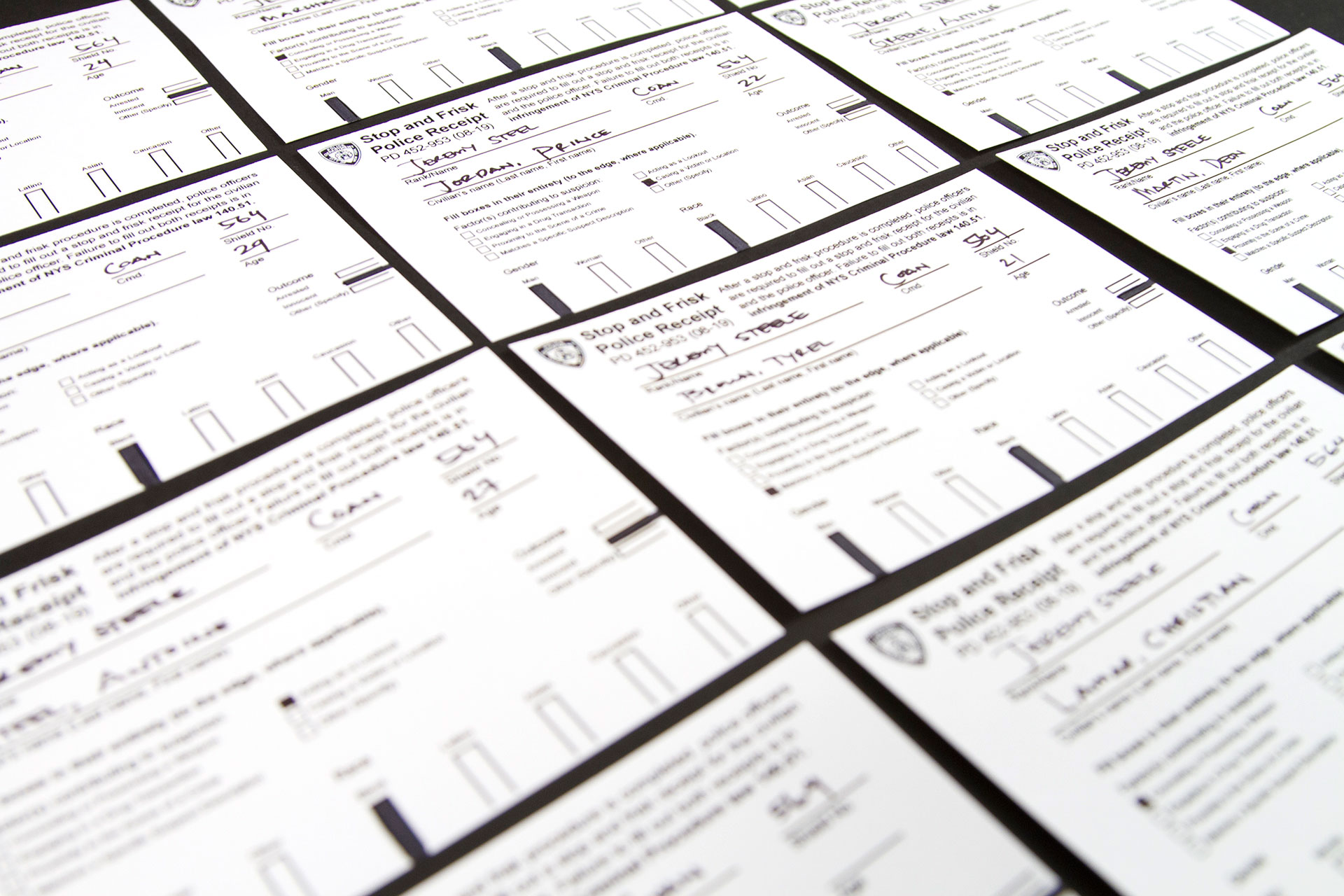

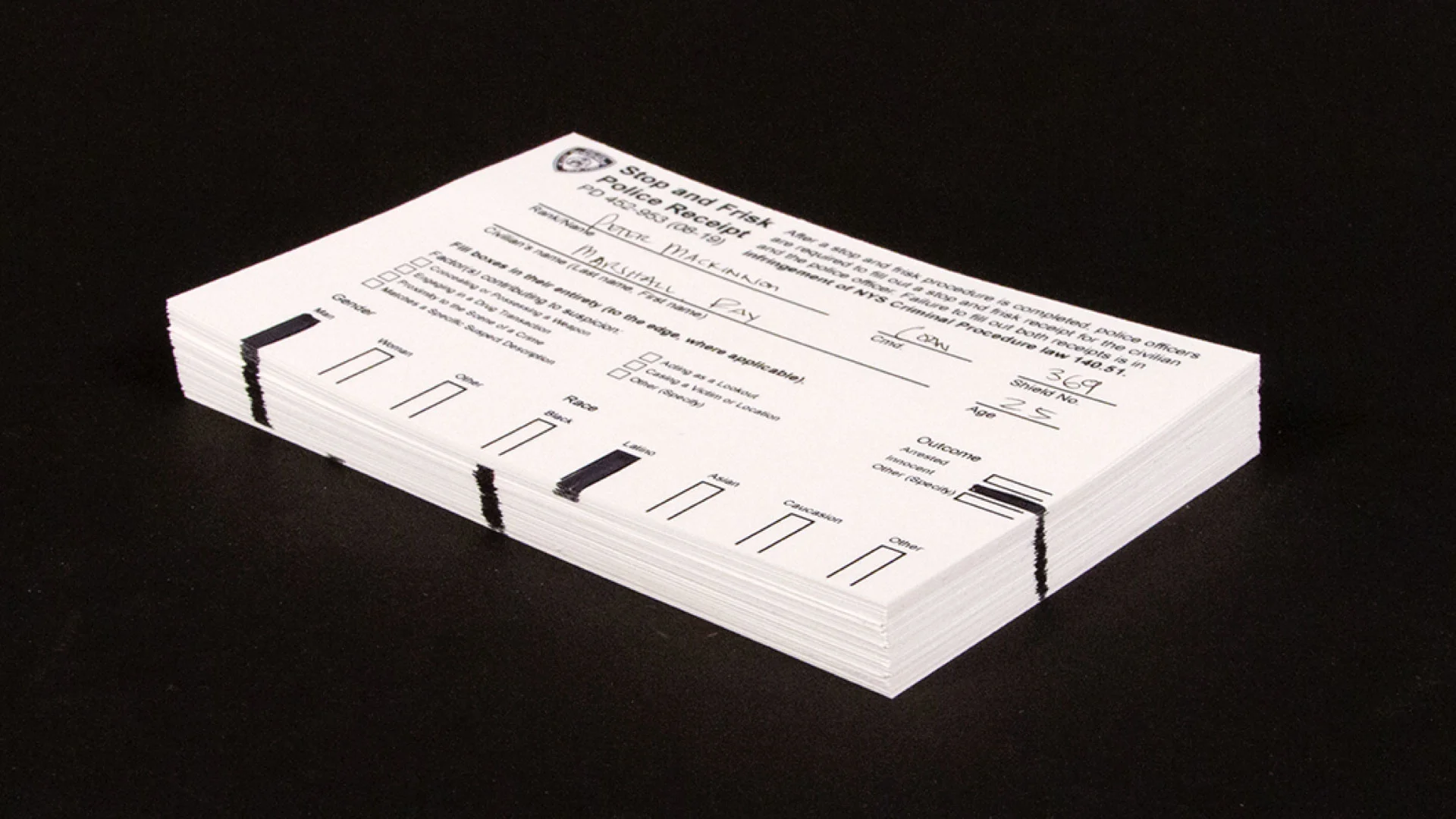

Tahnee saw this as an opportunity for design, and conceived a simple intervention called Stop The Frisk. The intervention makes the receipt a 2-part exchange—one includes the original form given to the civilian by the officer, and a new form, designed by Tahnee, to be kept by the police. The form for the officer to keep makes note of the civilian’s name, age, factors contributing to their suspicion, gender, race, and ultimately, the outcome of the procedure. Stop The Frisk requires police officers to keep copies of these receipts for their records. Her hypothesis is that after filling out a high number of these forms, the stack of receipts will create a three-dimensional visualization of the officer’s behavior—and his tendencies to engage in the stop-and-frisk activity. Perhaps after time this will persuade precinct leadership to make changes to this overused, ineffective policy.

“This is a business that is disturbing to me…but what I think is more disturbing is that we live in a time where I’ve been prompted to conceive of such a thing.”

Assurance

One of the more compelling interviews Tahnee conducted was with Peter W., a young Black man who was mistakenly detained, and brutally questioned, by the police to the point where a gun was held to his head. He said, “It was in that moment I was dehumanized. I realized how dispensable my life was.” This “dispensability” disturbed Tahnee.

After her interview with Peter, Tahnee reflected on the wide disparity between the value of lives. She was angered by the idea that “someone like Heidi Klum can insure her legs for $2,000,000, while the lives of young Black men are considered ‘dispensable.’” She wanted to question this imbalance through the lens of a speculative business called Assurance.

Assurance is an insurance company that provides body-part insurance—also known as surplus line insurance—at a low premium. This is in contrast to the current practice of insurance companies like Lloyd’s of London, who charge high premiums to people of influence, for surplus line insurance. Assurance’s low premium insurance would allow people in low income neighborhood, focusing on young Black men, to insure various body parts—particularly parts of their body used to provide their income. (David Beckham, for example, insured his legs for $195,000,000 while he was a soccer player.)

Conventionally, body-part insurance has been used most effectively as a publicity stunt to raise a celebrity’s profile. In this same vein, Assurance would roll out an extensive ad campaign, brining attention to the imbalance between celebrities and young Black men. The ad campaign would include billboards, subversive websites, and branded content on media sites like The Atlantic and The New York Times.

Assurance is a design of commentary. “This is a business model that is disturbing to me,” says Tahnee, “and I don’t believe that this business should actually exist. But what I think is more disturbing is that we live in a time where I’ve been prompted to conceive of such a thing.” Assurance is a piece of design that amplifies the sentiment ‘all lives matter’—and reveals its deep untruth.

Speak Easily

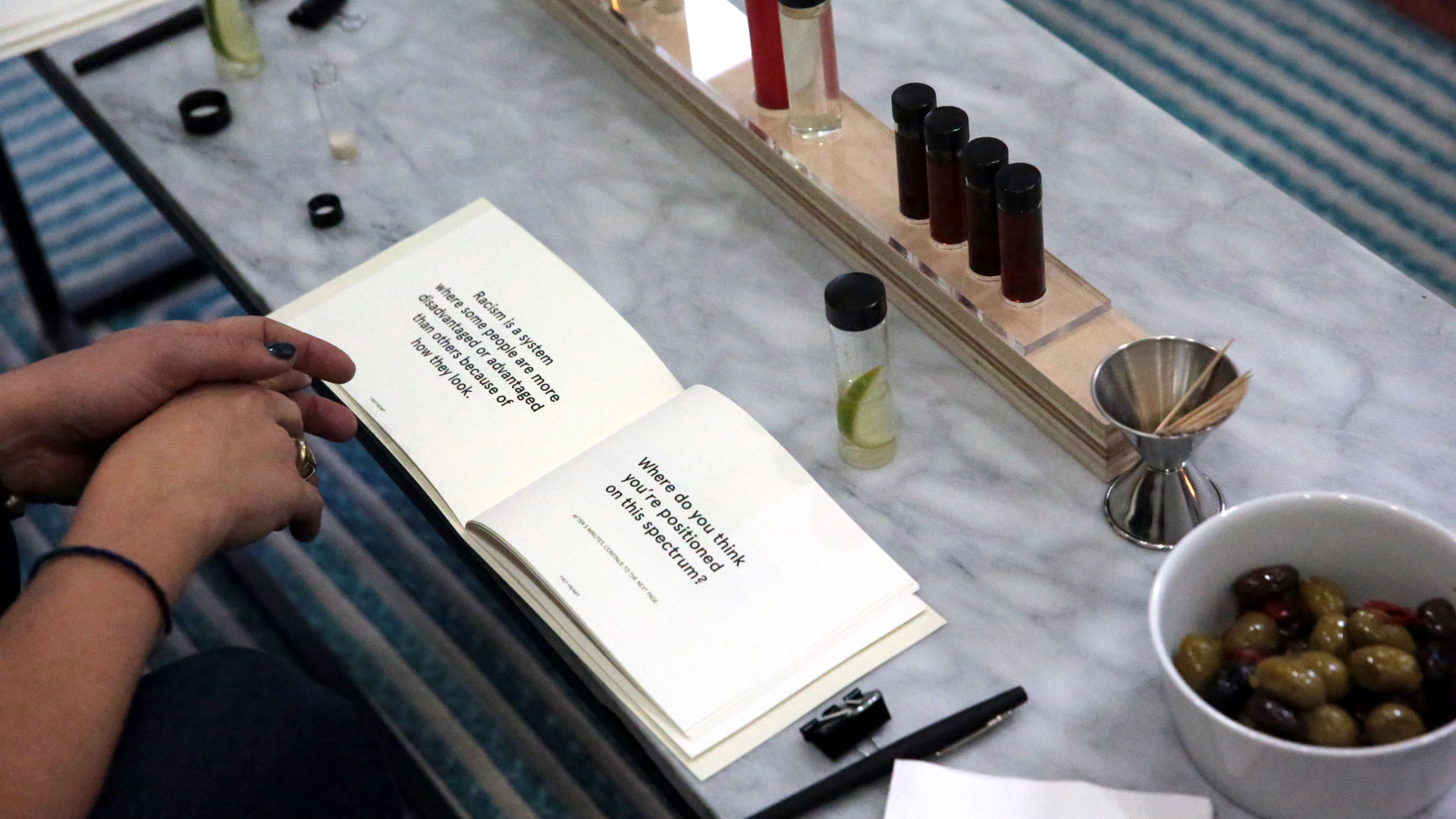

ahnee experienced a lot of resistance when discussing her thesis with others. When she talked about “racism,” “violence,” and then followed up with “intimacy” it made many people uncomfortable. DeRay McKesson, one of the leaders of the Black Lives Matter movement, told her that when you talk about racism, people go on the defensive; they assume they are automatically at fault. But DeRay also impressed upon her that “we can’t address what we don’t talk about.”

Encouraged by DeRay’s interview, Tahnee set out to find a way to have people—particularly people of privilege—talk about racism in a way where they didn’t feel defensive. So she created a piece of experience design.

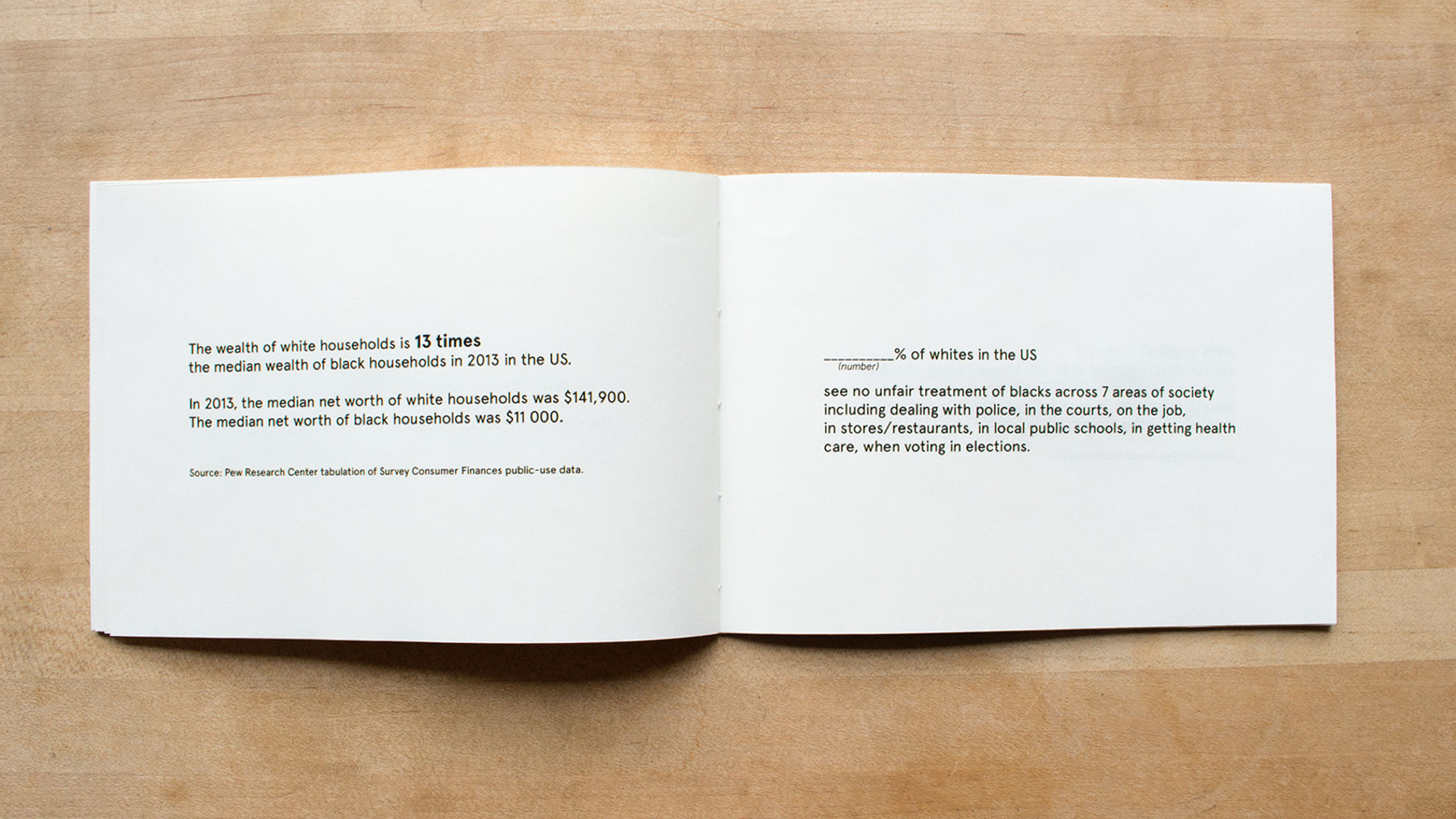

Speak Easily is a pop-up speakeasy that Tahnee held over a two-week period throughout various locations around Manhattan. She invited two participants to a secret location, where they would be guided through a conversation on race through the creation of cocktails. The guide included activities about privilege, drawing from the influential essay White Privilege: Unpacking The Invisible Knapsack by Peggy McIntosh. Participants read statistics about the disparity between races, and provoked participants with quotes from Between The World and Me about the visceral nature of racism. Participants were tasked with creating cocktails that visualized their answers and the character of the resultant conversation.

Feedback from the participants of Speak Easily was very encouraging. One of the participants spoke with Tahnee a few days after the experience, telling her how the conversation had changed her perspective on her everyday life: Experiences that were quotidian and mundane were now filtered through a lens that showed her the implications of race.

Online, there is freedom of speech, but also freedom from consequences.

Sans Consequence

Language played a key role in Tahnee’s thesis. Speak Easily was successful because it got people talking, but Tahnee knew that a model like this would likely not work on our biggest forum: the internet. Online, there is freedom of speech, but also freedom from consequences, allowing different parts of the web to be rife with racist rhetoric. As a response, Tahnee designed sans consequence, a conversational user interface that flags when a phrase or term with racist undertones is used.

A conversational user interface is an interface where users interact in the same way they would with a human—through platforms like email or text messaging—but where they interact with an artificial intelligence instead. (Current models are Amazon’s Alexa, Apple’s Siri, or Microsoft’s Cortana.)

Here’s how sans consequence works: Within the context of an email or text messaging, users start to type their message. When a trigger phrase is typed—for example, “I don’t see race,” sans consequence will highlight that text and then autocompletes it to include contextual information that reveals why the phrase is problematic. For example, in the case of “I don’t see race,” the autocomplete would write, “...because I occupy a space of privilege that allows me to ignore the oppression of others.” Other examples of trigger phrases would include “all lives matter,” “I’m not a racist,” and “race has nothing to do with it.”

Ultimately, the reason these phrases are problematic is because they dismiss the experience of many Americans. “Similar to Stop the Frisk, I wanted to provide a moment of pause for the user to consider the words they use, and the meaning behind those words,” says Tahnee.

“Someone’s body language can tell us what they mean faster and more honestly than their words can.”

Incline

he importance of language was pivotal for Tahnee’s thesis, but she acknowledged that the words we use “account for only 7% of communication.” Referencing Albert Mehrabian, Professor Emeritus of Psychology at UCLA, she cites that 93% of effective communication is non-verbal, and the majority of that—55%—is body language. “Someone’s body language can tell us what they mean faster, and more honestly, than their words can,” Tahnee reveals. Following the the path of Speak Easily, Tahnee created a set of furniture called Incline as a way to help facilitate difficult, uncomfortable conversations—and germane to her thesis—particularly difficult, uncomfortable conversations around racism.

Incline facilities difficult conversations by changing the attitude and placement of the participants’ bodies. Included in the set is a pair of chairs and table. Each Incline Chair has a sloped seat that tilts the pelvis forward. This tilting encourages the spine to be upright, with shoulders relaxed, increasing the capacity for breath and putting the user in a position “to better hear the other person.”

The Incline Table brings two individuals together—both physically and metaphorically. The table is constructed and engineered such that the tabletop surface “shrinks in length” over a ten-minute period—imperceptibly nesting the wooden slats over the static base. As the table shrinks, the participants find themselves “scooching” their chairs forward to maintain a comfortable sitting distance from the surface edge. Craftily, this results in the participants moving closer and closer together. “Through the movement of the two sides coming together, and the choreography of the bodies moving their seats forward, I’m hoping that the Incline table will bring people to a place of common ground,” Tahnee offers. “The intention behind the design is to position each person to be receptive to the other; to make room for their understanding through the physical openness of their bodies.”

Exploring her own traumatic experience through her thesis has given Tahnee the opportunity to understand the dynamic between violence and intimacy. Her exploration has led her to believe that we must look to the body and to the individual felt experience in order to effectively challenge racism and other violent experiences. “It is worth remembering that great violence can also be met with great courage.”

Learn more about Tahnee Pantig’s work at tahneepantig.com, and contact her at tahnee.pantig[dot]gmail[dot]com.