Designed To Reconnect: Shifts In Everyday Food Habits For A Less Wasteful Future

Emma Brigaud’s thesis, Designed To Reconnect: Shifts In Everyday Food Habits For A Less Wasteful Future, investigates resilient and sustainable food practices within the shared spaces of a neighborhood: where we live, shop, and learn. As witnesses to climate change, consumers often feel paralyzed by despair and inaction. However, households are responsible for fifty percent of food waste in the U.S. which requires a shift in our everyday food habits.

“Reducing food waste isn’t just about what we throw away.

It’s about how we live, share, and reconnect with where our food comes from and who we share it with.”

Through an exploration of the New York food system, Emma discovered that closing the psychological distance between people and the origins of their food requires a shift: knowing your food and knowing your neighbor. In conversations with chefs, educators, farmers, and municipal leaders, Emma identified opportunities to reduce waste, directly and indirectly, along the food habit lifecycle. Her work proposes playful and meaningful interventions that re-enchant our relationship with produce, turning a system of commercial waste into one of care, connection, and delight.

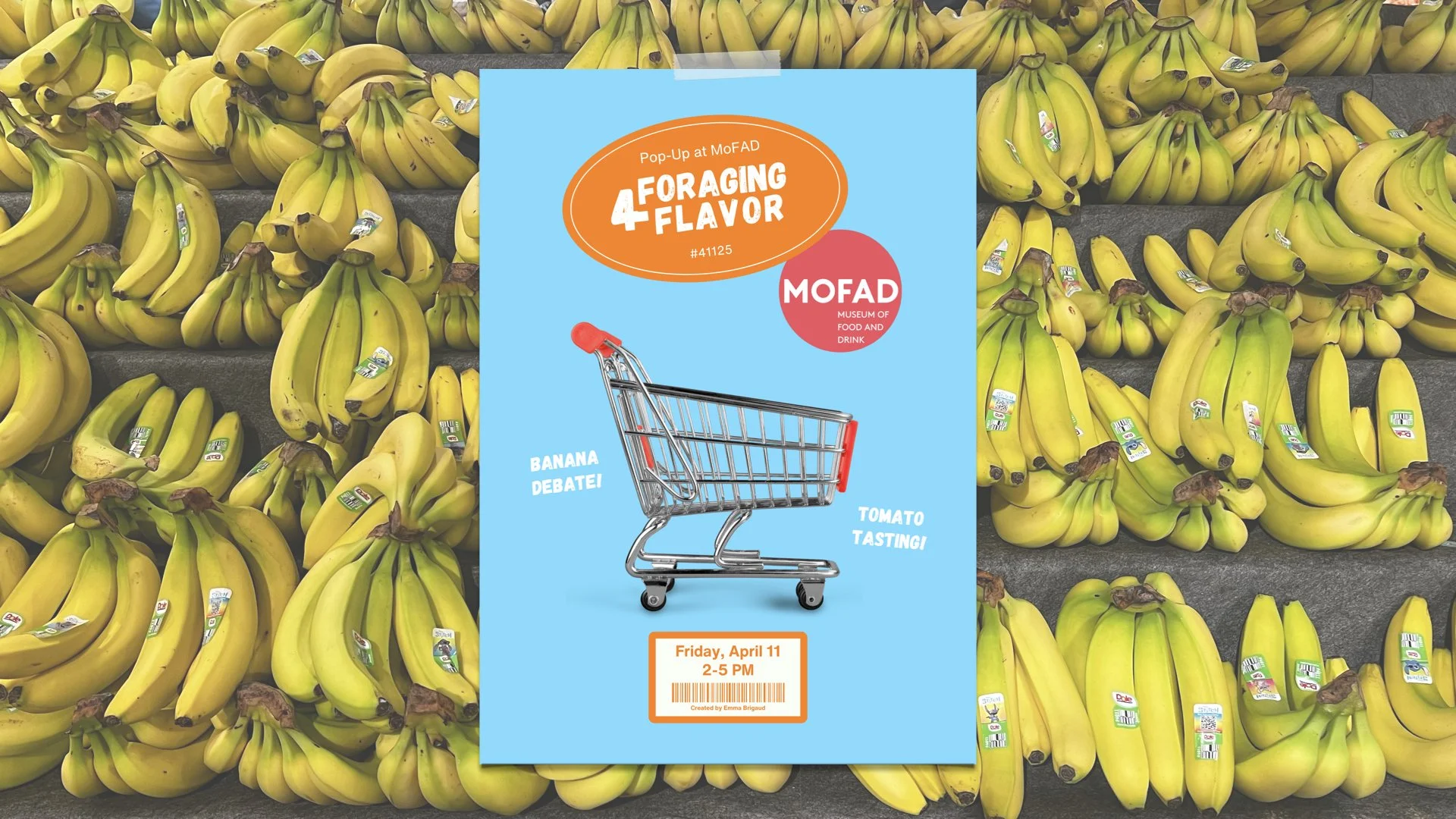

Foraging 4 Flavor

What if buying produce was more like foraging: exploratory, intentional, and seasonal? “When we go in search of edible wild plants, we attune ourselves to what’s available,” Emma explains. “There’s an element of surprise and delight in the discovery of what nature has to offer.” Meanwhile, in the produce aisle we reach for strawberries in the winter and sigh when our nectarine goes bad a day after being placed in the fruit bowl. Both of these scenarios are a direct result of the cold chain, which is responsible for transporting our commercial produce from farm to store.

What if buying produce was more like foraging: exploratory, deliberate, and seasonal?

A tomato is harvested before it’s ripened, spends significant time in refrigerated trucks and warehouses and then forced ripened before it’s placed on the shelf. Year-round supply comes at the cost of flavor, producing tomatoes with thick skins and bland, mealy flavor as the cold breaks down sugars. Still, many of us aren’t ready to give up tomatoes on sandwiches in January—but, as Emma wondered, “could the experience of tasting the difference start to nudge us toward more sustainable choices?”

To experience this concept, Emma created Foraging 4 Flavor: a pop up at the Museum of Food and Drink—an experience that invites visitors to explore the relationship between ripeness and flavor to reveal how commercial produce manipulates both. Emma noted that participants were quick to notice their preferred banana, but discerning what makes a locally grown tomato taste so much better than one that’s commercial required more careful inspection.

“A bad tomato tastes like guts!” - Foraging 4 Flavor Pop-Up

Fruitprint

People are personally offended by bad fruit. Online, Emma found reactions like “Depressing,” “Ruined my entire month,” “Soul crushing.” And in an interview someone exclaimed, “Why have I never learned how to select a perfect melon?!” These comments may seem dramatic, but as the Foraging 4 Flavor pop up revealed, there’s truth to their bitterness. Language is one of our superpowers and a form of agency. If we can articulate our preferences, we can start to demand better from the companies who supply our produce.

Language is one of our superpowers and a form of agency.

If we can articulate our preferences, we can start to demand better from the companies who supply our produce.

As an extension of the Foraging 4 Flavor experience, Emma was inspired to empower shoppers in the produce aisle to personally invest them in choosing better produce. This led her to create Fruitprint, a digital tool to build your skill in picking fruit that’s ripe and worth your money. In the store, shoppers can reference a quick sensory checklist. For example, distinct netting on melon indicates it had more time to ripen on the vine. At home, they can evaluate the flavor and use that input to guide the next purchase.

Overtime, people will begin to realize that brown spots are not rot but crystallized sugar and scars are signs of time spent naturally ripening in the sun. The real power of Fruitprint isn’t just choosing well, it’s learning what made it good. And when we know that, we can avoid waste, eat with the seasons, and shift demand toward better farming practices.

How do you select for peak ripeness and flavor when the difference isn’t so visible?

Hourfruit

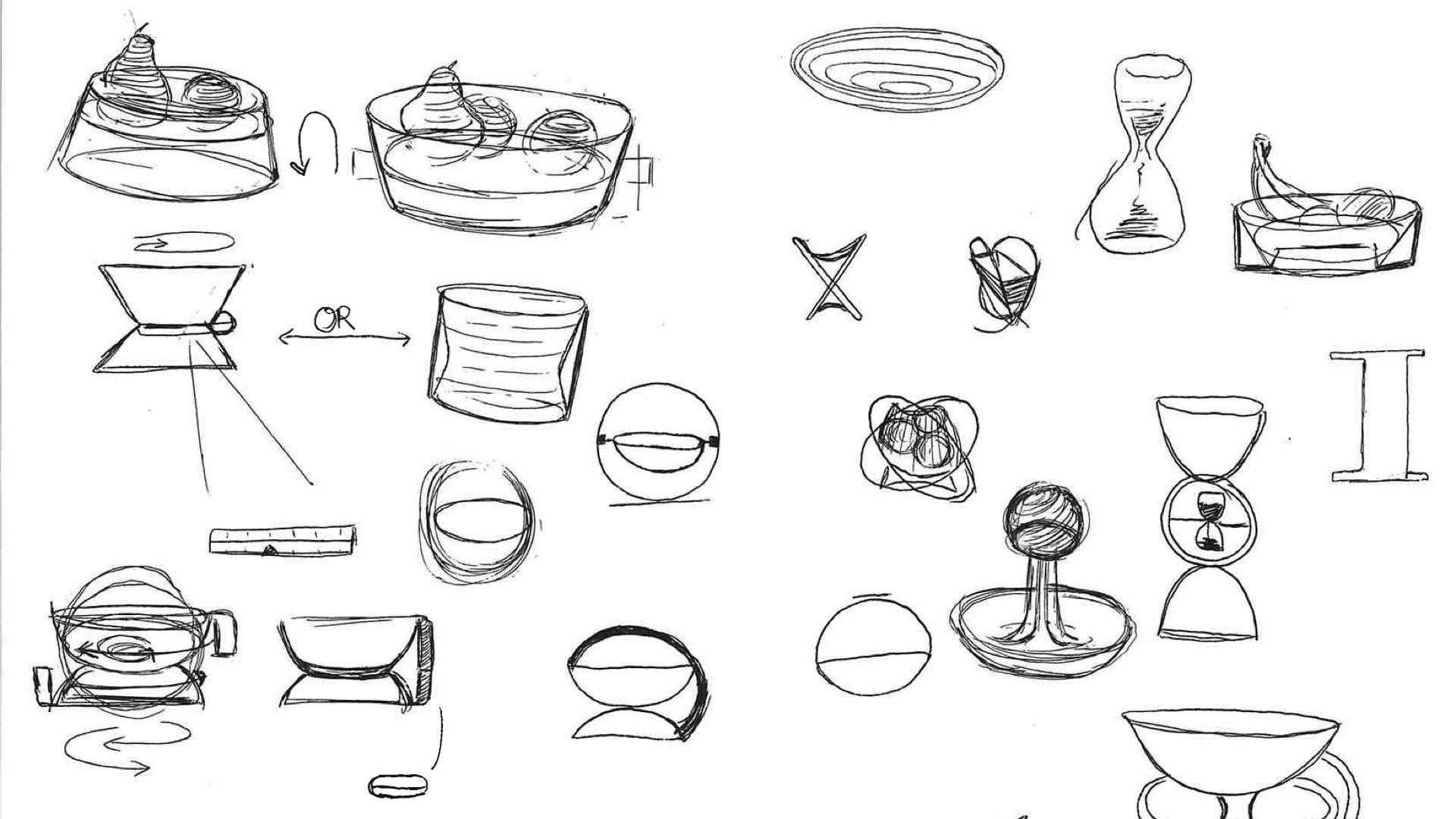

Hourfruit is a timed fruit bowl that needs to be flipped every other day prompting a simple daily ritual: check each fruit and determine if it’s ready to eat. If it’s not, return it to the bowl for another rotation. When the handles align, repeat the ritual.

“I buy fruit all the time excited to eat it and then completely forget about it.

It becomes a decoration on my counter and I don’t think to check until it’s two days too ripe.”

— Monty, Brooklyn

Much of our produce shouldn’t be stored in the fridge. Countertop storage like a fruit bowl is visible but even the most enthusiastic consumers forgets to eat their fruit, thus leading to waste. Emma set out to create storage that is not only visible but invites active participation from the members of a household to notice the changes.

“Even just moving your produce you can tell you if something has changed. You can release the scent as you pick it up.

It’s really a human thing to touch and be in conversation with our food.”

— Participant in Concept Testing

The design for Hourfruit emerged after several rounds of sketching and prototyping, exploring different ways to convey time and prompt interaction. In early concept testing, Emma returned to Alison Mountford, a food waste chef and educator she interviewed in the Fall, who was in favor of the playful bowl as a low-tech solution to promoting the enjoyable and conscious consumption of fruit to prevent waste. Taking the form of an hourglass, Hourfruit is not only a beautiful addition to a countertop but a clever approach to being in touch with your fruit.

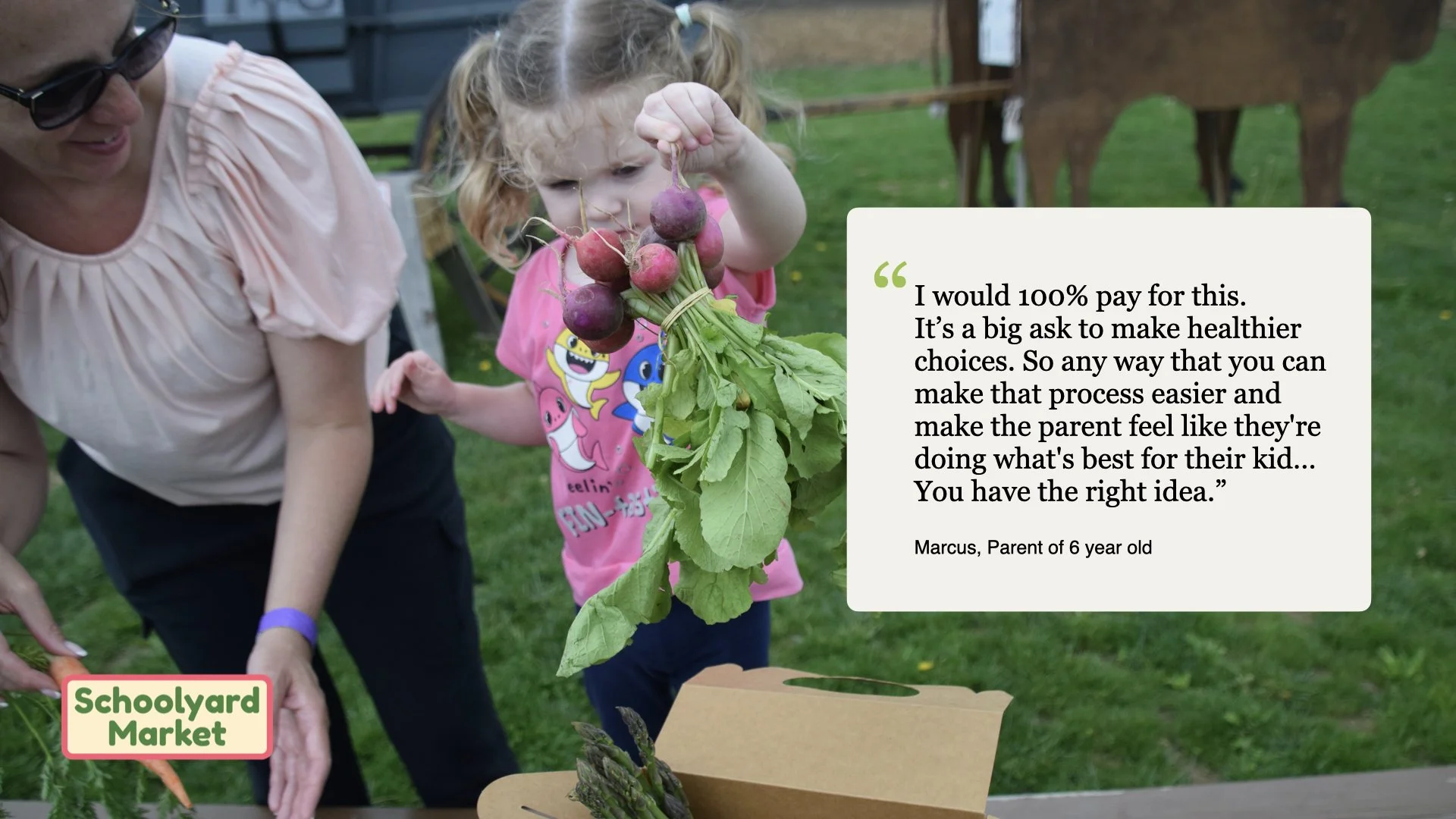

Schoolyard Market

What if we made seasonal and local eating fun, affordable, and a part of the school routine? With this question in mind, Emma developed Schoolyard Market, a box of produce delivered at school pickup, designed for kids and their families. Students receive local produce delivered monthly at school. But it’s not just a box of veggies: it’s a mini curriculum, designed into the packaging, so families can learn through doing. Seven percent of American adults think that chocolate milk comes from brown cows. This may seem silly but it’s less surprising when you learn that one in three children don’t know where their food comes from. As much as she focused on the habits of current consumers, Emma found herself turning toward future-consumers. How do we teach sustainable food literacy?

If we want the next generation to shape the better version of our food system, we need to start with how they learn and interact with food. One model that provides direct access to quality produce and food origins is Community Supported Agriculture (CSAs). But most CSAs are for adults with barriers like higher upfront cost, inconvenient pickup times, and little engagement designed for children.

How do we teach sustainable food literacy?

The content in each panel was carefully curated with consideration for the kid’s journey and a parent’s capacity to plan and facilitate hands-on education. On their way home, students can learn about the month’s harvest, with images that indicate how they come from the ground and interesting facts that build anticipation for giving them a try. In the evening, parent and child can follow an easy recipe to make a plant-based meal. In the spirit of introducing new sustainable behaviors, families are also prompted to place food scraps back into the box to drop-off at their nearest compost site.

The box eliminates friction: No loose papers, buried emails, or planning. Even if they’ve never participated in a farm share, this one feels easy. As one parent highlighted: “I would 100% pay for this. It’s a big ask to make healthier choices. So any way that you can make that process easier and make the parent feel like they're doing what's best for their kid…”

The impact of Schoolyard Market extends beyond a healthy, shared meal. From touring a vertical farm and markets to consulting farmers and CSA founders, Emma was also intentional in creating a service and product that could support small farmers and sustainable agriculture. Schoolyard Market supports farmers by increasing awareness and lowering barriers to acquiring new CSA members. As for the next generation, it builds food literacy and healthy habits through sensory interaction and storytelling. And for the planet, it reduces waste by promoting seasonal eating and composting.

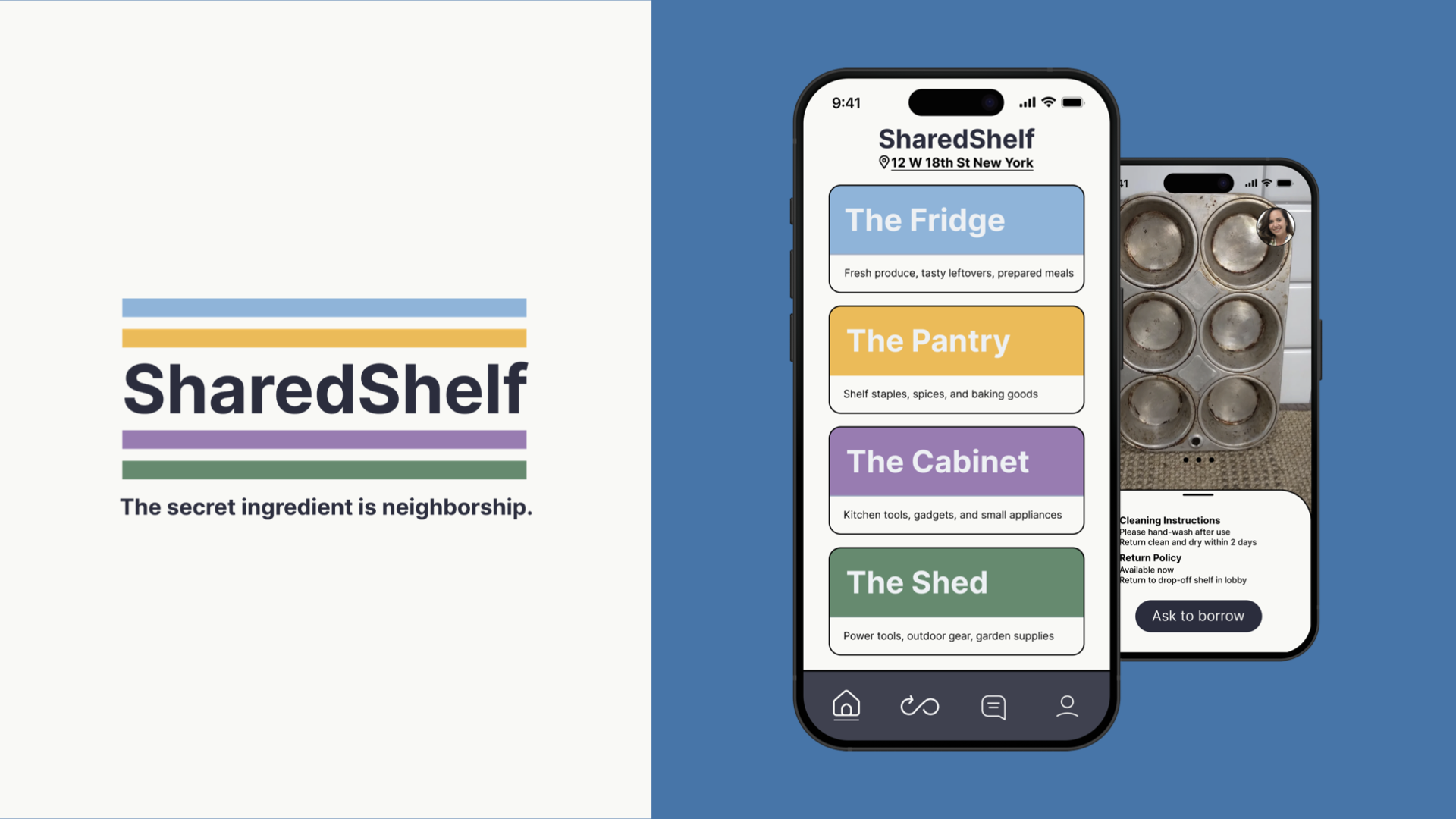

SharedShelf

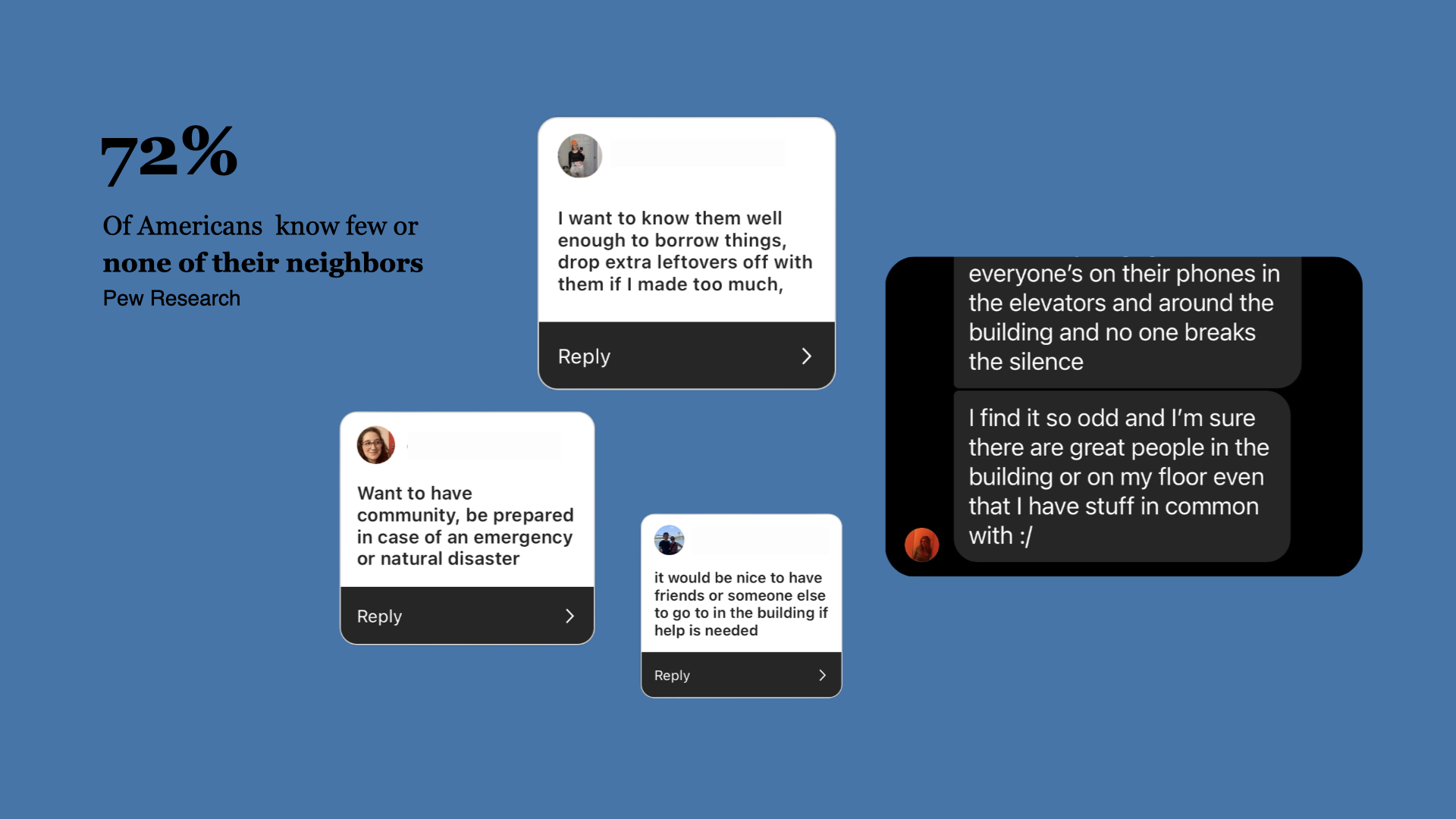

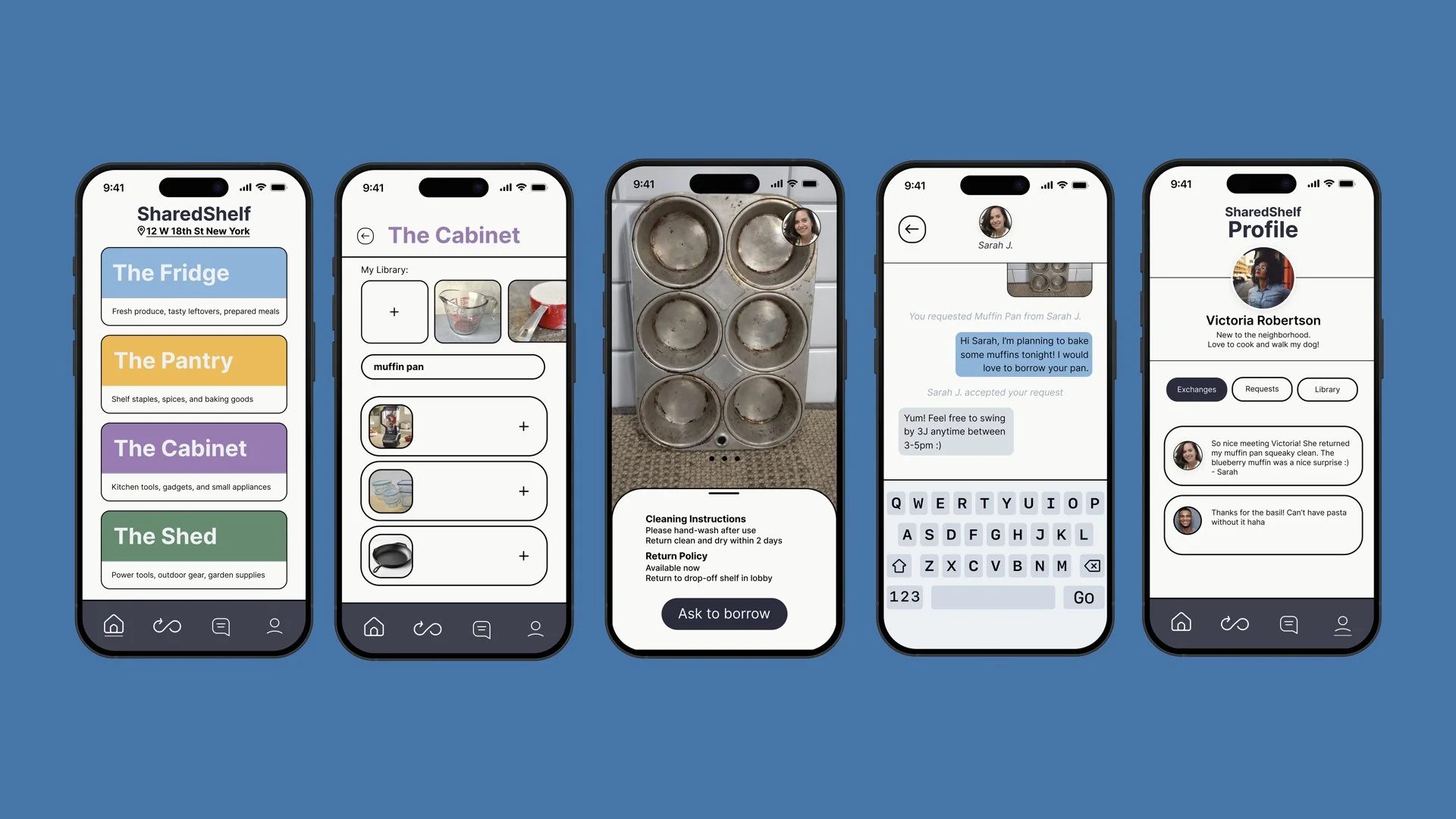

How do we turn waste reduction into a shared, neighborly act? Emma sought to tackle one of sustainability’s toughest challenges: turning intention into action. Behavioral science shows that people are more likely to change when they see others doing the same—yet in cities like New York, many neighbors barely know each other. What if reducing waste could also build community? SharedShelf is a hyperlocal lending platform designed to make sharing household items, ingredients, and tools simple—and social. By creating visibility into what neighbors have on hand, the platform lowers the barrier to connection and encourages reciprocity.

Knowing what your neighbor has on hand, lowers the barrier to making a connection.

It’s not only convenient but facilitates care and reciprocity.

We need Neighborship. Emma realized her task was twofold: facilitate a way for households to lessen their waste while opening the door for connection beyond a passing hello in the hallway. As Ayana Elizabeth Johnson writes in What If We Got It Right? Visions of Climate Futures, “One of the best things you can do to prepare for a disaster is to bring your neighbor a basket of muffins, because you have to get to know them before the storm. Building community cohesion and resilience is important.”

While peer-to-peer lending isn’t a new concept, Emma identified clear gaps in existing models like Facebook Buy Nothing Groups and Nextdoor. These platforms often lack a sense of place-based community and rely on users to initiate requests, which can feel awkward or intrusive. Unlike these existing groups, SharedShelf offers a more structured, building-based network where sharing becomes the default. Features like perishability nudges, reciprocity guidelines, and clear availability listings make lending and borrowing feel intuitive, safe, and neighborly.

In early concept testing, Emma explored user willingness to lend and borrow within a smaller, more structured network, specifically within residential buildings. When framed as a building-supported service, participants reported feeling more open to sharing, especially if they could see what items were already available. This visibility removed the guesswork and reduced the social friction of asking for a favor.

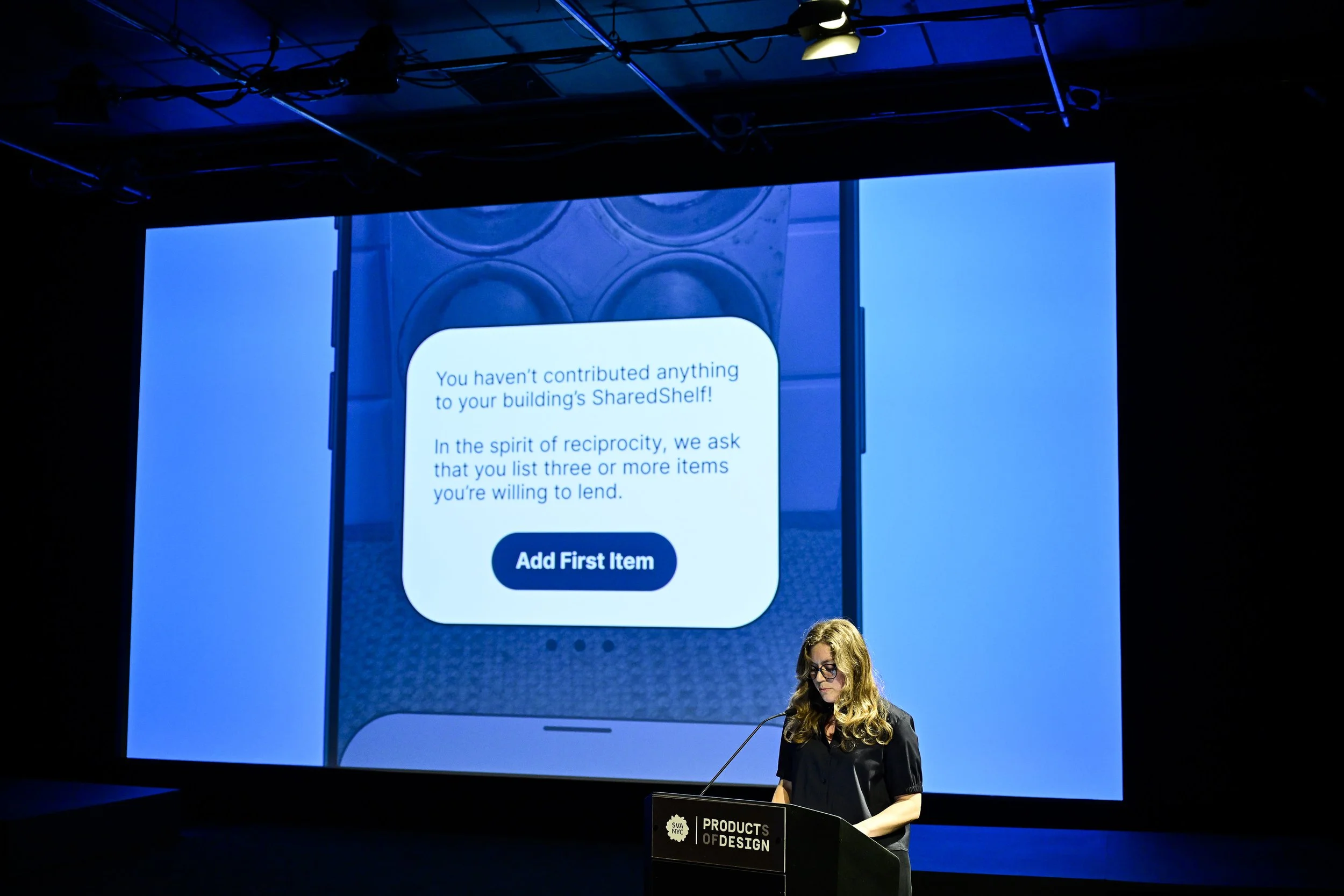

Trust and safety were common concerns, particularly around perishables or high-use kitchen tools. To address this, SharedShelf includes features that promote care and accountability: a reciprocity guideline to encourage participation in both lending and borrowing, and time-sensitive nudges that guide neighbors to make use of listed perishables before they go to waste. These subtle design choices help build a culture of mutual support, making everyday exchanges feel less like transactions and more like small acts of shared stewardship.

For a deeper look into Emma’s thesis process, research, and reflections, explore the following links:

Thesis Repository on Notion – a comprehensive archive of Emma’s thesis development

Thesis Blogposts on Medium – extended reflections and insights

emmabrigaud.com – Emma’s design website