Closing the Loop : A Participatory Workshop

This article was written by Zai Thakoor ’25 and originally published on her thesis blog.

In the journey to explore the lifecycle of products and their often-overlooked end-of-use phases, I hosted a participatory design workshop, Closing the Loop, focused on repair as a lens for understanding emotional, practical, and cultural relationships with objects.

The workshop brought together individuals from Turkey, Kurdistan, US, India and Ukraine from diverse work backgrounds, inviting them to reflect on their choices around repair, reuse, and disposal. Here’s what unfolded:

The workshop was designed to:

Examine repair as a shared cultural practice: How do different cultural narratives shape attitudes toward repair?

Understand emotional connections to objects: What role does repair play in fostering pride, memory, or closure?

Investigate barriers to repair: Why do individuals choose or avoid repair, and how can design make repair more accessible?

Explore end-of-life choices: How do these decisions reflect personal values, identities, and priorities?

Icebreakers and Share-Outs

The first few questions discussed —

How is repair defined in your home country?

How did it feel when you repaired something or got something repaired

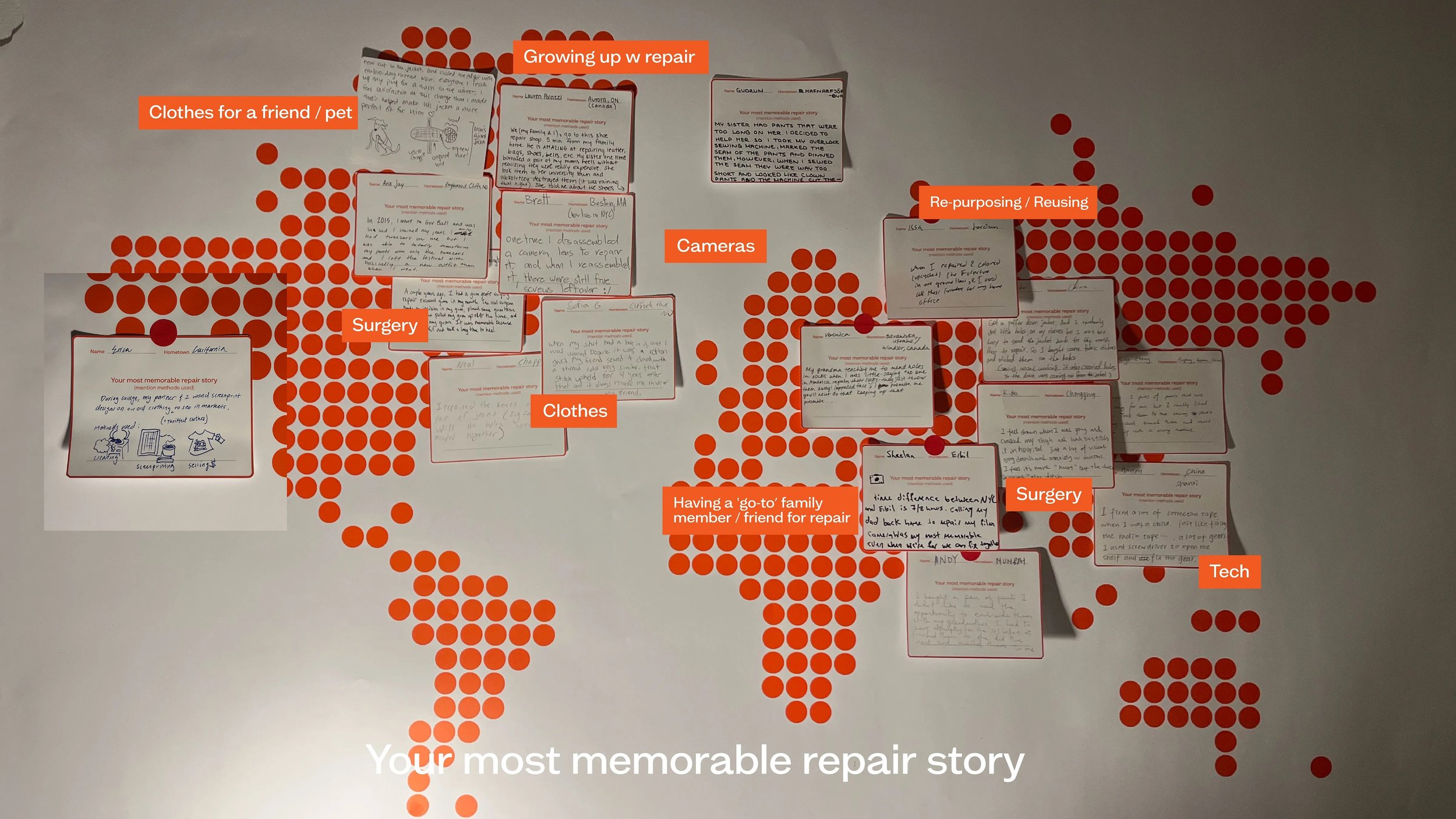

Share a memorable repair story

Bingo

Bingo cards with various repair or end experience scenarios (e.g., “Replaced a phone battery,” “Mended a torn shirt,” “Stopped a gym membership,” “Repaired a relationship”). Participants circle the ones engaged with. The goal was for participants to recognize repair as a concept beyond clothing, spanning different industries and life situations.

The exercise exposed diverse repair habits, such as reusing damaged items in new ways or seeking professional repair services.

Participants discussed issues like corporate overproduction and marketing tactics that discourage repair and encorage “timely maintenance ”

Emotional attachment often dictates whether an item is repaired or discarded, with participants highlighting the guilt or satisfaction tied to their decisions.

“Emotional attachment often dictates whether an item is repaired or discarded, with participants highlighting the guilt or satisfaction tied to their decisions.”

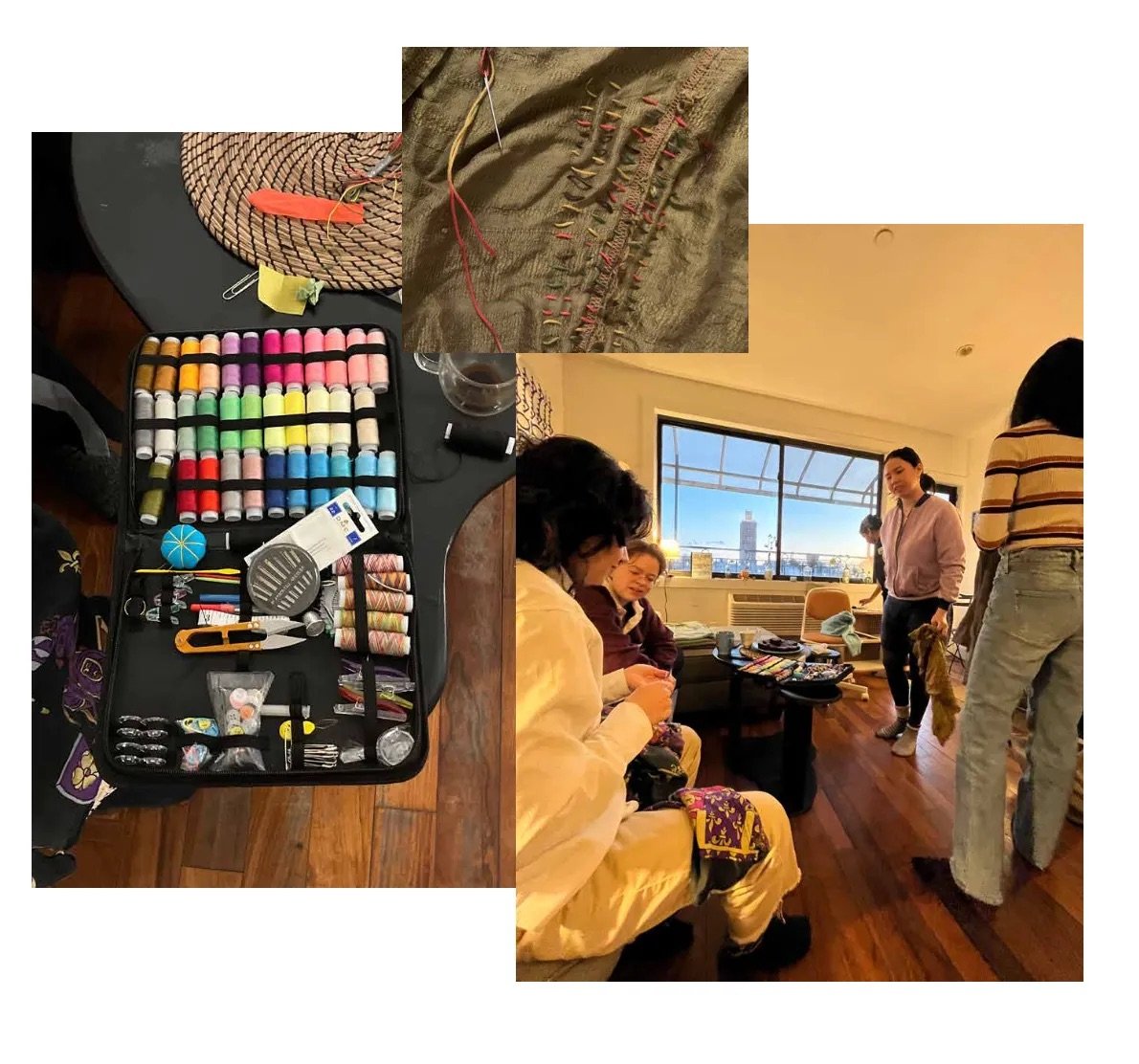

Mending

Garments brought to the session reflected a mix of practical needs (e.g., socks with holes) and deep emotional significance (e.g., thrifted or inherited items).

“Even though fixing this small hole would me 30 minutes, I know I would never find the ‘right’ time to do this”

The act of repairing in a group fostered connections, with participants sharing stories about the garments’ journeys and repair challenges.

Obituaries and Re-labelling

Writing obituaries for garments’ “old lives” helped participants reflect on their relationship with objects and the emotional closure repair provides.

Re-labelling old garments symbolized renewal, bringing a sense of accomplishment and ownership.

The activity highlighted the importance of rituals and personalization in repair, transforming functional acts into meaningful practices.

Successes

The communal setup encouraged interaction and learning, making repair approachable for even the least experienced participants.

The activity design brought emotional depth to the act of mending, turning functional repairs into meaningful reflections.

Fails

Time constraints meant some participants couldn’t complete their repairs, leaving them feeling unfinished.

A lack of initial instruction left some beginners unsure of where to start, highlighting the need for clearer onboarding

How Do Choices Tell Us About People?

The workshop revealed that repair decisions are deeply personal, shaped by values, memories, and practical considerations. A choice to repair rather than replace can signify resourcefulness, sentimentality, or a commitment to sustainability. Conversely, avoidance of repair often stems from systemic barriers — like convenience-driven norms or lack of access to tools — rather than a lack of care.

Each stitch told a story: a desire to hold onto something meaningful, a creative impulse to transform, or a quiet act of resistance against disposability. These choices illuminated how our relationships with objects mirror our identities, priorities, and the worlds we wish to create.

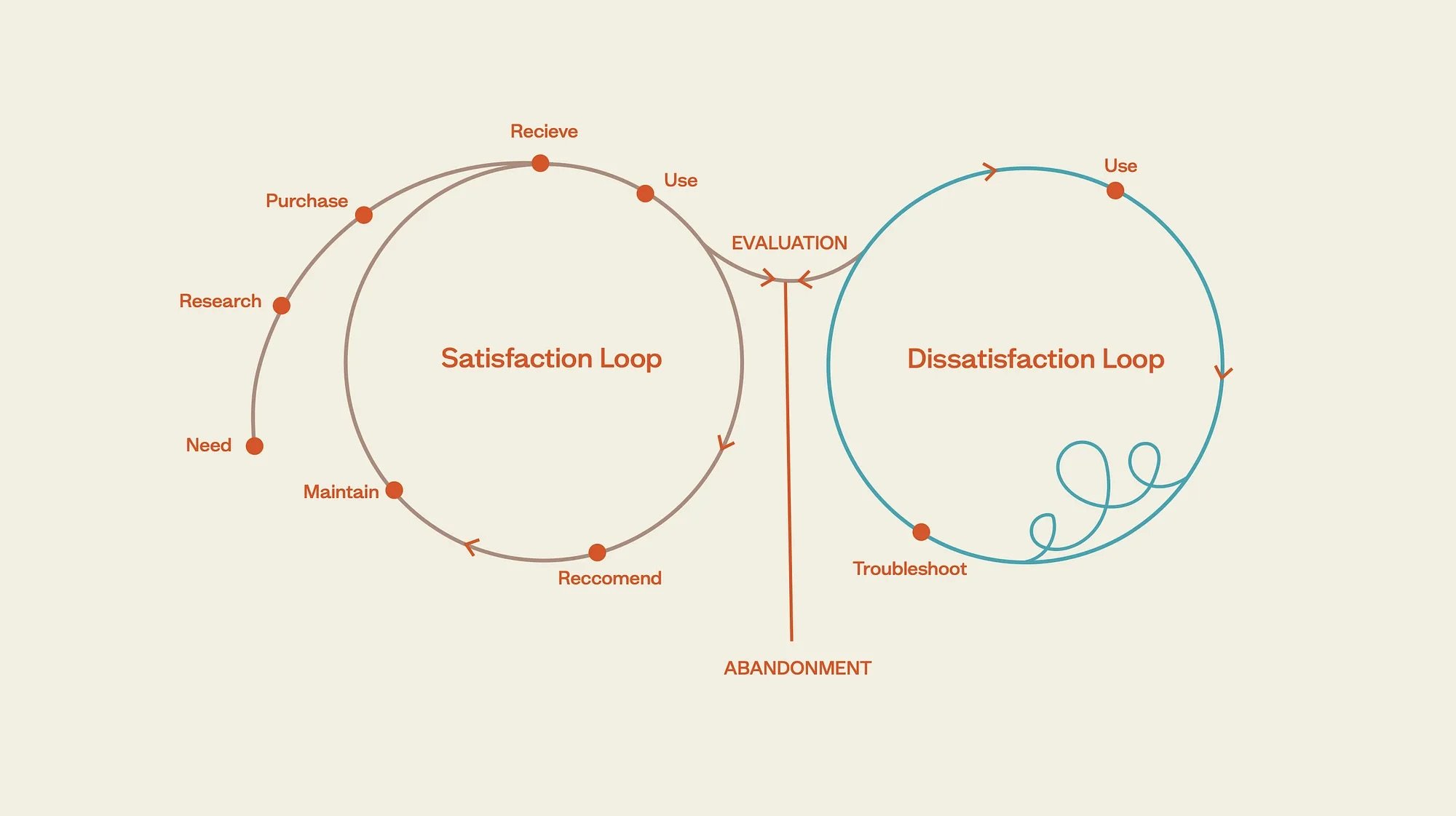

But these choices also fit into a broader framework. The loop maps the lifecycle of an object, from acquisition to use, through moments of evaluation that lead to either repair, reuse, or abandonment. Here’s an example of a typical satisfaction loop, based on participant reflections:

“Each stitch told a story: a desire to hold onto something meaningful, a creative impulse to transform, or a quiet act of resistance against disposability. ”

Evaluation: A critical turning point where the object’s value is questioned. It may stem from damage, obsolescence, or changing needs.

“The strap broke, and I wasn’t sure if fixing it was worth the effort.”

Decision: The user chooses between repair, reuse, or abandonment based on emotional connection, perceived value, and available resources.

“I decided to patch the torn lining because it still holds so many memories.”

Renewal (or Discard): If repaired or reused, the object often returns with a renewed sense of purpose and attachment. If discarded, it becomes a source of loss or guilt.

“Mending my jeans gave them new character — I’m even more attached to them now.”

***

I wish to continue working on this loop as a structural device to shape my thesis (hopefully not just a theoretical tool; but a way to reflect on our everyday choices).

Read more about Zai’s thesis here.