From Ambiguity to Clarity: The Case for ‘It Sucks That’

This article was written by Harsha Pillai ’25 and originally published on her thesis blog.

When I started design graduate school, I immediately noticed a stark difference in how things were done compared to my undergraduate studies in architecture. The most obvious distinction? Frameworks. In design school, every stage of a project has a tangible output — some kind of physical artifact. In architecture school, the initial research phase was more fluid; we sketched, compiled decks on a neighborhood’s history, and studied the current zoning and potential, but we weren’t explicitly creating personas or forming How Might We (HMW) statements. Instead, the process was more intuitively led.

This structural contrast extends beyond academia. Many product designers structure their portfolios using the same design frameworks, while architecture portfolios tend to lack a standardized format. On one hand, a structured approach provides clarity, but on the other, an intuitive approach allows for more organic exploration.

The Problem with How Might We

When I first encountered How Might We questions, they felt overly formal. Something about the word might made the phrase seem detached, adding unnecessary complexity to what could be a simple, straightforward question. This is a personal tendency — many designers thrive with this framing. However, last week, one of my thesis professors, Kristine Mudd, introduced us to an alternative approach: It Sucks That. This framework and reframing exercise are adapted from Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg.

This approach strips the problem statement to its core. It forces clarity and directness.

Reframing from HMW to It Sucks That

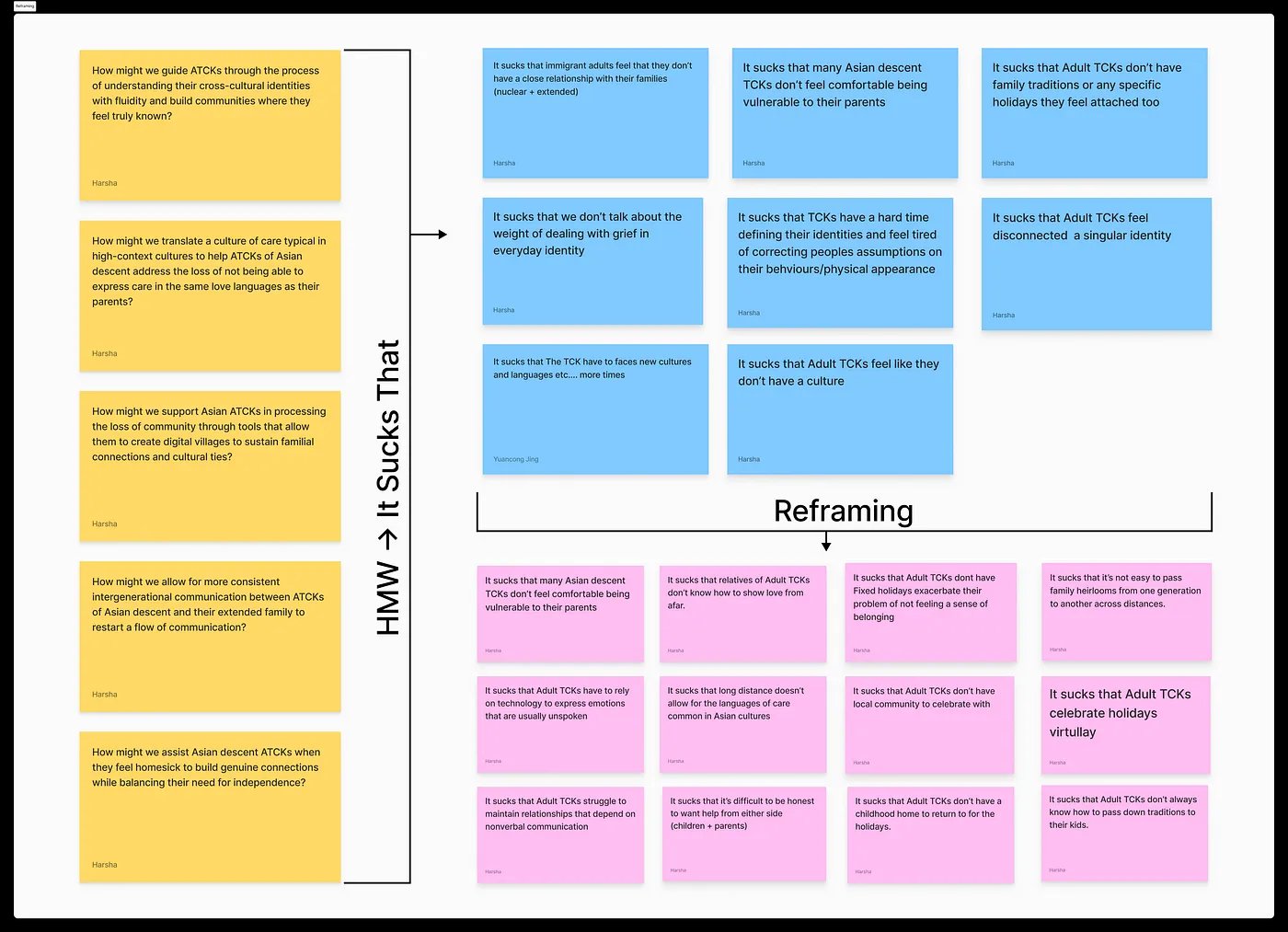

Showing the transition from How Might We to It Sucks That.

Above is a snippet of my FigJam board illustrating this shift. The yellow sticky notes represent the five How Might We statements I developed in the fall semester following my research. The blue sticky notes capture the initial It Sucks That statements, where I deconstructed each HMW question to ask: why is this really a problem? The pink sticky notes represent an additional iteration, where I further unpacked the issues identified in the blue notes.

Walk Through Example: Deconstructing a HMW Statement

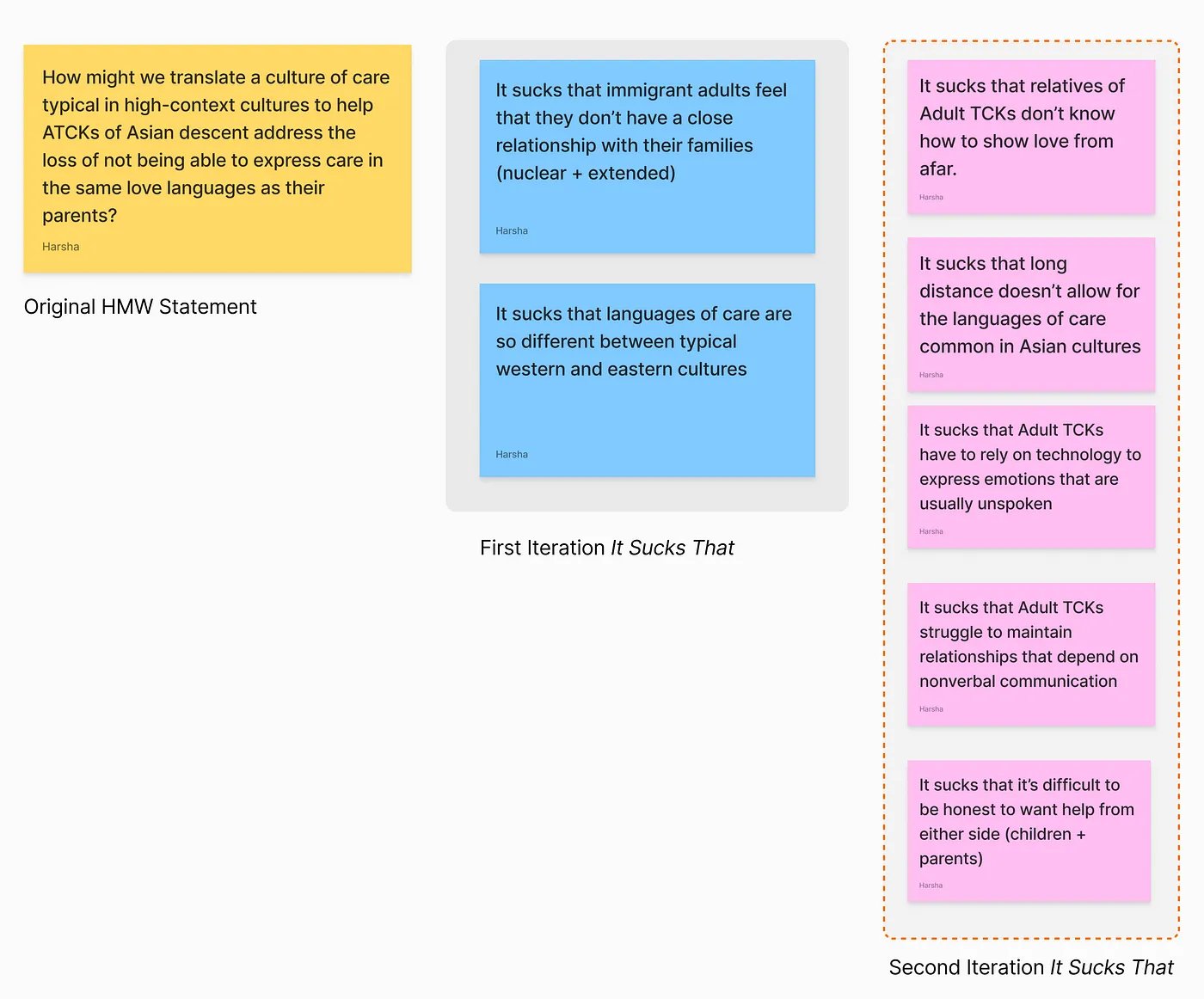

Example of how to move to It Sucks That.

Let’s examine one transformation. At the end of the winter semester, I felt strongly about this How Might We:

HMW translate a culture of care typical in high-context cultures to help ATCKs of Asian descent address the loss of not being able to express care in the same love languages as their parents?

That’s a lot packed into one HMW question. It’s wordy, and it doesn’t immediately expose the core problem. This is where It Sucks That was incredibly helpful.

So, what really sucks about this?

It sucks that adult TCKs of Asian descent struggle with close relationships because they don’t know how to show they care.

It sucks that languages of care differ so drastically between their home culture and the culture they study, live, and work in.

But that’s still broad. What are the deeper implications? Who else is affected?

It sucks that extended family members who live abroad might not know how to show care to an adult TCK.

It sucks that current long-distance communication tools don’t accommodate care languages typical in Asian households.

Harsha and three classmates during an afternoon-long brainstorming session.

From Problem Oriented to Solution Oriented

This reframing led directly to ideation. If the problem is that long-distance communication doesn’t support expressions of care, maybe we need alternative tools. Maybe extended families need structured ways to reach out. Maybe technology isn’t the right solution, and analog methods would be more effective. In my research last year, I found that letter writing fosters deeper connections because it requires sitting with one’s words before sending them. So now, the conversation shifts from problem-identification to actionable solutions.

One of my first ideas for Kristine’s class is a ready-to-ship postal system featuring prompts and sticker emojis that visually depict languages of care in Asian cultures. I’m now exploring linguistic translations and how to leverage high-context communication as a design strength.

Like all things in design, no single framework is universally superior. But this shift was a revelation for me. It allowed me to generate more solutions while helping others better understand what I was trying to solve. It’s been liberating to realize that I can break free from frameworks that don’t serve me. While I appreciate the structure they provide, I also value the intuitive problem-solving approach I honed in architecture school.

Design frameworks should serve the designer — not the other way around.

***

You can read more about Harsha’s thesis here.