MASTERS THESIS: Shift: A Proposal to Lift Community Morale, by Andrés Iglesias

Andrés Iglesias’ masters thesis, Shift: A Proposal to Lift Community Morale, explores two principal ideas: the effect optimism has on the way people see their environment, and how focusing on “the good” around you—rather than focusing on the flaws—can be crucial for the recovery of depressed communities.

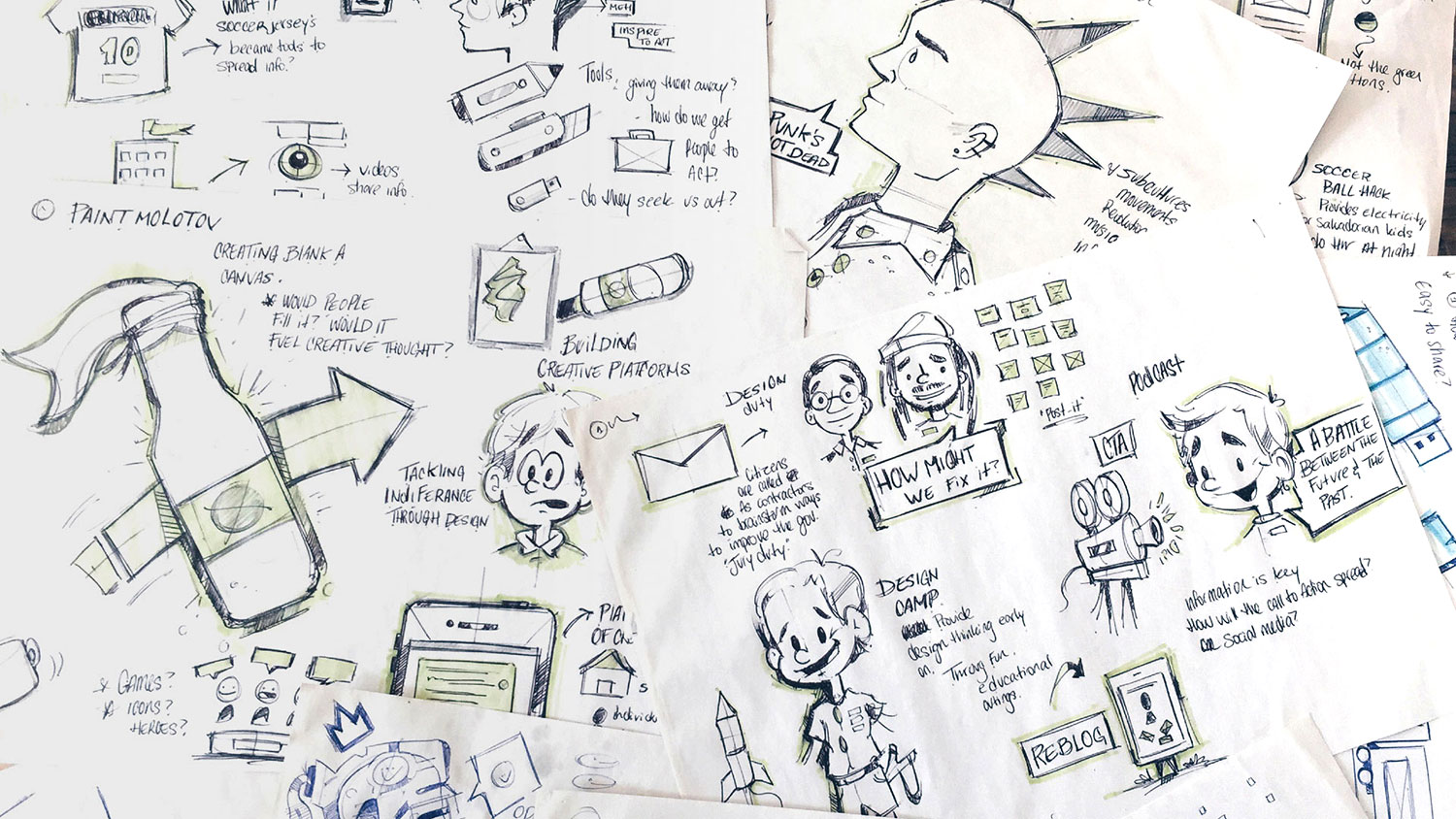

The project moved through many phases—from research on positive psychology, to designing a collection of conceptual objects, to creating a platform for community collaboration. Using disposable cameras as the prompt, the thesis culminated in a neighborhood-wide scavenger hunt for “the good.”

As the first generation to grow up since the war’s end, young Salvadorans have the chance to dream of a future beyond the confines of armed conflict, and—if they dared to be optimistic—to create one.

Andrés was born in El Salvador, a small Central American nation long plagued by corruption, violence, and an ever-growing gap between the rich and the poor. Andrés spent his pre-thesis summer reading about the history of his country and how a decade-long civil war left it scarred with many of the maladies that affect the country to this day. Early in the research, Andrés spoke with Aritz Bermudez, a young Guatemalan entrepreneur, who offered that as the first generation to grow up since the war’s end, young Salvadorans have the chance to dream of a future beyond the confines of armed conflict, and—if they dared to be optimistic—to create one.

Fall research focused on the notion of revolution—the ease with which it can spread, and its unapologetic tone. Key insights came from interviewing psychologists, political figures, and young entrepreneurs who argued that that the issue at hand was not one of violence and corruption, but rather one of low morale in the community. Positive cognitive psychology—an area of psychology that studies the strengths that enable individuals and communities to thrive rather than focusing on the crippling social issues that affect them—was founded on the belief that people want to live meaningful lives and cultivate their best qualities in order to enhance their experiences of love, work, and play. It posits that psychology should shift its focus from repairing the negative to focusing on what is working; what’s positive, and that we can learn from.

Andrés formulated a hypothesis: In order to lift a community’s morale, the proper tools and platforms must be in place for individuals to share and showcase what is good around them. Some of the tools he designed included a paint-filled Molotov cocktail, which, when thrown, creates a blank canvas to be filled with collaborative solutions, along with a slingshot that uses paint balls to cover the neighborhood in bright colors. Andrés also designed three conceptual apps: Radio, Amigos, and Hola, providing platforms and services that allow community members to collaborate together in group projects, speak their minds freely through live podcasts, and generate positive headlines about the good that they felt was being overlooked in their neighborhoods.

Andrés was forced to deal with some unexpected (yet perhaps predictable) feedback: Accusations that the magazine’s design aesthetic was elitist and “inappropriate” for its audience; that the magazine’s “good design” wasn’t congruent with the neighborhood it was meant to represent.

All of these tools fuel conversation, and Andrés realized that designing platforms that acknowledge negativity’s role in reducing morale could create a shift in the community’s perception of itself. To further test his ideas, Andrés designed Chunche, a platform that allows users to “share the good going on in their neighborhoods through photos and stories.” Andrés originally pitched Chunche as a print publication. Each month, a new edition—showcasing one neighborhood’s moments of good—would be printed and distributed. The content of the magazine would be crowd-sourced; people in the neighborhood would be contributing the photography and content.

The feedback Andrés gathered from those in his neighborhood was extremely positive, and lots of people became involved. After sharing his concept and findings with experts in the field of design however, Andres was forced to deal with some unexpected (yet perhaps predictable) feedback: accusations that the magazine’s design aesthetic was elitist and “inappropriate” for its audience; that the magazine’s “good design” wasn’t congruent with the neighborhood it was meant to represent.

Andrés asked: “Why are some entitled to so-called good design, while others are not? I refused to talk down to my neighbors, and I made it my primary goal to design products and services that they would be proud to be a part of, and excited to contribute to.” And in addition to the print version, Andres created its digital version.

Swinging the pendulum back, Andrés concluded this thesis work with a full-scale analog production of Chunche. Working with local bodega owners in his Brooklyn neighborhood of Bedford Stuyvesant, he left disposable cameras in each, along with a simple set of instructions: “Go find the good around you and photograph it. But please do bring it back.” After several days, many cameras were returned (sadly, a few never made it), each becoming a vehicle for capturing the good around Bed-Stuy...defined by its residents.

Andrés comments: “the camera allowed individuals to capture fleeting moments of optimism in their neighborhood, and to experience them literally through a new lens.” He selected several of the photographs, composed them into a series of posters, and then distributed the posters around the neighborhood. “Developing the cameras and finding that my neighbors were actually going out and finding good around them was a pretty magical moment for me,” he adds. “Each snapshot is evidence that taking pride and ownership of your environment truly can create a shift—building momentum to inspire change.”

The final phase of the project will be to take Chunche back to his home of El Salvador, working with neighborhoods to help them elevate the good.

To learn more about Andrés’ work, visit mynameisandres.com or email him at aiglesiasj[at]gmail[dot]com.