PERMANISM: Towards the Obsolescence of Disposable Furniture

Not more than 50 or 60 years ago, the idea of "disposable" did not exist; the physical objects in our lives were intended to be with us for a lifetime...or longer. Today, the convenience of disposability in the United States has become the status quo, and everything from packaging to electronics to even large-scale items like appliances and furniture are now considered throw-away. Spurred by our imperative for constant economic growth, our consumerist culture is having a detrimental impact on our environment. Judy Chi’s master thesis, Permanism: Towards the Obsolescence of Disposable Furniture, looks to reengage people with the physical products in their lives as "objects of permanence."

In previous eras, ownership—especially of large items such as furniture—was a lifelong contract that ended with the succession of the heirloom to the next generation. In today’s global economy, we not only have the ability to choose from a sea of products based on our personal preferences, but also to "change them out" many times over based on our evolving tastes and living situations. In 2013, the Environmental Protection Agency reported that the amount of furniture (and furnishings) waste generated had more than doubled in the U.S. in the last 40 years—from 28 pounds per person annually, to 73 pounds.

“By making mundane, disposable objects out of precious materials, can we change the relationship people have with them?”

Precious Prosaic: Challenging Our Definition of Disposability

Judy investigated several strategies to disrupt this cyclical pattern of buying and throwing away. In her early interventions, she used deception and manipulation as an approach to changing behavior. She explored incentives "to compel people to commit to objects for life" by subverting their definitions of "luxury" and "cheap". She asked, “By making mundane, disposable objects out of precious materials, can we change the relationship people have with them? Can these objects become things we buy once—and keep for life?” To prototype this, she created Precious Prosaic, a set of paperclips designed in solid gold.

Celebrity Ad Campaign: “Stop Throwing Shit Away!”

Continuing on this path of manipulation, Judy's next intervention leveraged the power of advertising to influence behavior. "It’s no secret that ad campaigns have incredible sway in shaping opinions and choices," she argues, "but instead of using these tools to push products and promote consumerism, what if they were used to promote sustainable actions?" Employing the power of celebrity endorsements, she developed a speculative ad campaign to encourage better consumption habits. In one billboard, Ricky Gervais, using his usual dose of profanity, urges the “intelligent people of the world to stop throwing shit away.”

And again below, Louis CK similarly prompts Americans to stop buying disposable furniture.

Judy found that even in cases where people say they want to act responsibly, actions often did not match expressed intentions. Her research into behavioral economics revealed that humans have limited cognitive capacity; they become immobilized when overwhelmed with a flood of information and choices. In today’s internet-connected world, there are a myriad of data points and options bombarded at us, all demanding our attention and requiring decision-making. People shut down after a certain point. According to University of Chicago economist Richard H. Thaler and Harvard Law School Professor Cass R. Sunstein, inertia also plays a huge role in human behavior. In their book Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness, they authors cite studies that demonstrate how even in situations where people are offered “free money” for their retirement account, nearly half do not choose it—if it requires action on their part.

Judy also learned that the economic and cultural systems in place contribute to bad habits. In the United States, capitalism and its demand for ever-expanding growth have been ingrained into society. Indeed, Americans are encouraged to consume at voracious rates. They’re even told that consumption is "good for prosperity"—as if it is each citizen’s civic duty to continually shop. With this in mind, Judy turned to strategies that could fulfill consumer needs without requiring them to exert additional effort.

“While my initial explorations use manipulation to get people to do the right thing, my later efforts instead rely on making the right thing easy to do.”

Mapping the current landscape, she saw that if sustainable products and services had the same qualities that are so appealing in disposable products—convenience, low-commitment, affordability, and ease-of-use—then the likelihood of adoption would be much higher.

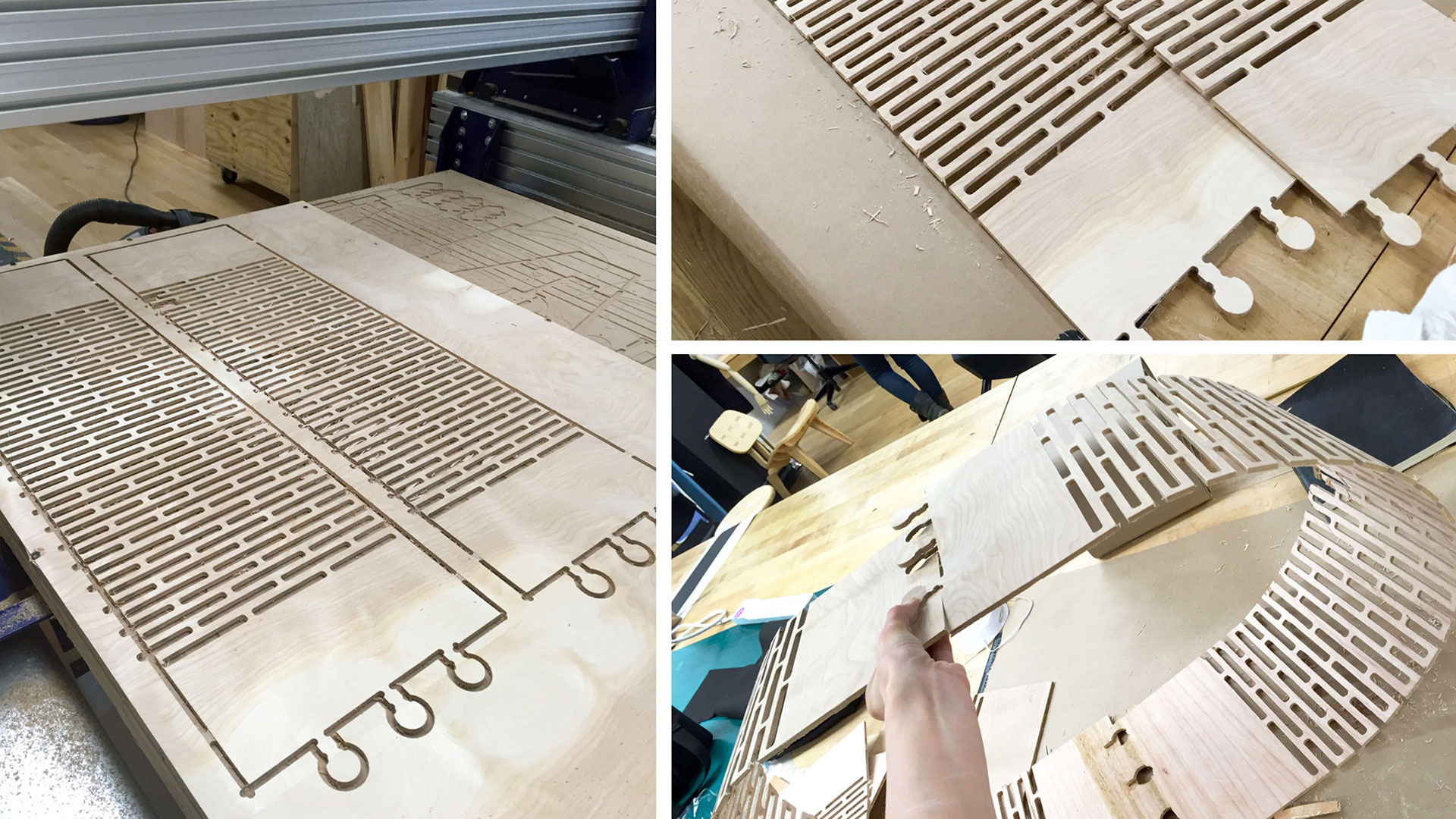

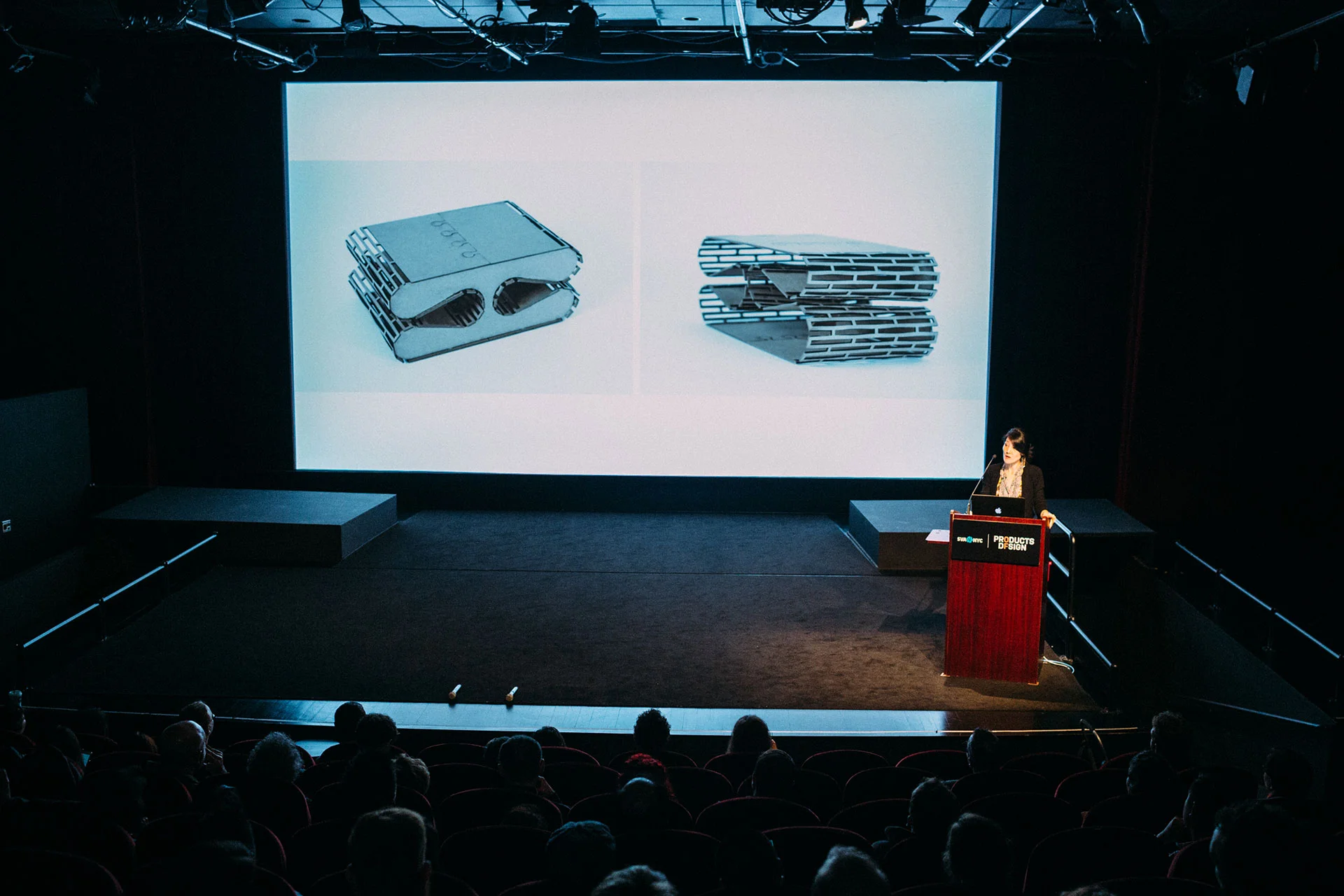

Lattice Furniture: Leveraging New Technology & Manufacturing Model

Looking to new fabrication technologies as a way to gain efficiencies, Judy created Lattice—a line of furniture that explores the potential of CNC (Computer Numerical Control) milling. With CNC, digital drawings are loaded into a computer, and automated cuts are made with an integrated router. The precision of this automation allows a series of uniform slots to be easily cut into a sheet of plywood, giving Lattice its flexible body.

This flexibility can form "living hinges"—replacing traditional metal hinges—and allowing side- and back-panel components to be made from one continuous sheet of wood. Implementation of a tabbing system for connections further reduces the use of metal hardware.

With this "pliable carcass," furniture can be devised to reconfigure depending on use. A shelf, for example, can compress down into a coffee table—which also allows for easy, flat-pack shipping.

Additionally, Lattice furniture embraces a different manufacturing and distribution model, which affords several advantages: Using open-source design, consumers are able to download drawings online for free, as well as take advantage of and contribute to improvements made through crowd-sourced designs. They can then build the furniture themselves, or take the drawings to their local digital fabrication shop to be produced for a reasonable fee. This decentralizes manufacturing from faraway places like Asia—reducing both the cost and the carbon footprint of shipping. Since furniture can be made-to-order, warehousing of materials and inventory is also reduced. "Lastly," Judy offers, "the product supports communities by keeping the value chain local."

Common Collection: Leveraging Under-Valued Materials

Instead of relying on "the next big technology" as a panacea, Judy considered materials that currently exist but are perhaps overlooked or under-valued. She began working with everyday, common resources—paper and cardboard—which already have a lower carbon footprint than traditional furniture components such as wood, metal or plastic.

She was influenced by the work of architect Shigeru Ban, who deftly employs simple cardboard tubes to create monumental structures. She was also impressed by the humble hollow-core door. It's a product that is seen as extremely low-end, but in fact its paper honeycomb core is actually a modern marvel of structural integrity. From these inspirations, she proposed a speculative brand called common collection, a line of sustainably-produced and -consumed furniture.

To offset the sense of cheapness that people often associate with lightweight furniture, the tube legs double as "piggybanks." Judy quips that the loose change that's added to the legs gives the table the heft and weight that people equate with value, while also literally increasing its value!

The first prototype in the collection is the Added Value Table, constructed of a cardboard honeycomb top and cardboard tube legs. To offset the sense of cheapness that people often associate with lightweight furniture, the tube legs double as "piggybanks." Judy quips that the loose change that's added to the legs gives the table the heft and weight that people equate with value, while also literally increasing its value!

Common Collection: Quattro Table & Bench

Elevating under-valued materials further, Judy created a wooden version of the table. She first mocked up a small composite panel, sandwiching the paper honeycomb between two boards of solid oak. (Instead of cladding the table with thin veneers like many furniture products do, a heavier, one-quarter-inch-thick solid wood exterior was used.)

Critical to imparting the warmth and character of solid wood, the grain direction of the oak cladding is laid out to be consistent with whole planks of wood: end grain cuts are used at the ends of the panel, side grain cuts used on the sides and flat grain cuts are used for the top and bottom. The corners are also mitered to further enhance this quality.

The Quattro Table in red oak uses this custom sandwich panel design.

The Quattro Bench in walnut also uses this sandwich panel design, but includes an additional refinement made to the top: The walnut top thickness is reduced, and backed with one-quarter inch thick birch plywood. The alternating grain directions in the plywood give it greater strength and stability, while also saving further on material cost.

Both the table and the bench incorporate corner blocking in order to keep the frame square and provide rigid connections to the legs. The cardboard-tube legs are wrapped in thick veneer, and are removable to allow for convenient, flat-pack shipping. This feature—combined with the lighter weight of the honeycomb core—further reduces its shipping carbon footprint. “By integrating cardboard materials thoughtfully with wood, it is possible to create products that are sustainable, affordable and durable," Judy offers.

Rather than exhibiting the honeycomb-and-wood product solution in a traditional furniture trade show venue, Judy chose to use the typology of a "personal training session" as a hands-on way to get participants to interact with the physical product.

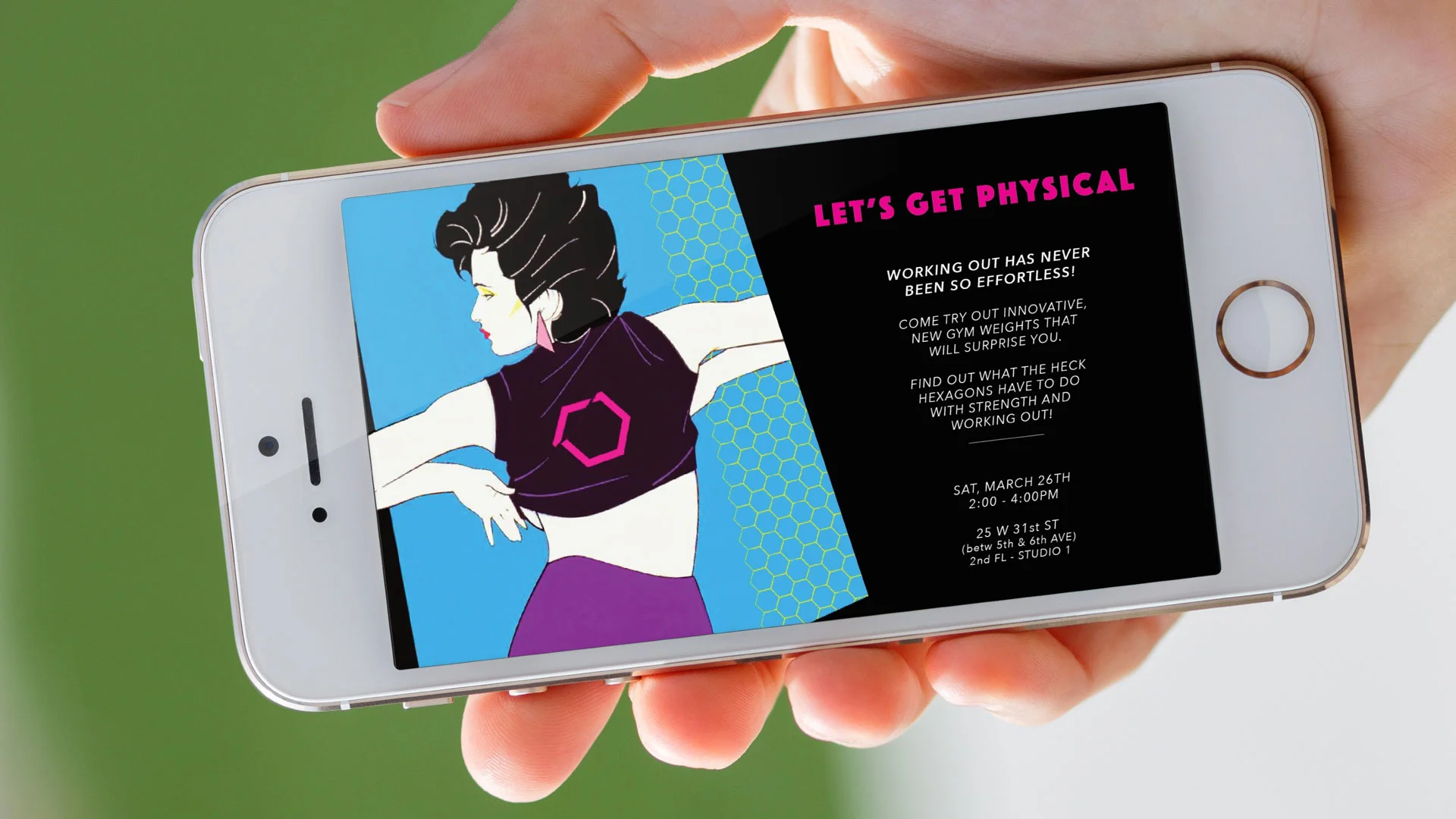

Let’s Get Physical: An Experience Design

When having conversations about sustainable furniture solutions, Judy found that people often became bored or even exasperated—sustainability had become an overused and meaningless word. She sought to design an intervention that was lively and fresh in order to reignite interest. Let’s Get Physical is an interactive experience—a venue for people to discover a new material combination using paper honeycomb and wood for sustainable furniture design—and employs the upbeat and outrageous vernacular of 80’s design to entice participants to take part.

Rather than exhibiting the honeycomb-and-wood product solution in a traditional furniture trade show venue, Judy chose to use the typology of a "personal training session" as a hands-on way to get participants to interact with the physical product.

And instead of making traditional furniture pieces like a chair or table to display, Judy made barbells in the same honeycomb and wood materials. This prototype design demonstrated how something that looks heavy, can actually be lightweight and still durable.

Participants were invited to a gym studio in order to “work out” with the barbells under the guidance of a “personal trainer.” Graphics on the mirrors with prompts such as “Grab It!” and “Squat!” further encouraged people to engage.

Judy was excited when participants began to really examine, play with, and even dance with the barbells, and her hope of generating delight and real physical interaction was realized.

At the end of the “work-out” sessions, participants were shown a cut-away sample and diagrams of the wood-and-paper-honeycomb construction. A small Quattro table prototype was also on display, and a healthy conversation ensued where important insights were shared. For Judy, the success was seeing people re-engage with real curiosity and interest in seeking sustainable alternatives.

In the age of the Internet and social media, we have the ability to exchange, sell, or share with others in our community. And we have the ability to foster a new kind of ownership that supports a sustainable future...Norman’s furniture items are given catchy names and anthropomorphic qualities. With these endearing personas, users would be less likely to mistreat the furniture.

Norman: Furniture Sharing Service with Wit

Wanting to reach a broader audience and looking to take advantage of the furniture stock already in existence, Judy next experimented with collaborative consumption. Unlike past generations that often inherited furniture, Americans now have the ability to choose furniture based on personal preferences, and can even regularly replace them with new items as tastes or living situations change. "But this freedom of choice and liberty from life-long commitment does not mean that consumers should continue to cycle through cheaply made, disposable products," Judy argues. "In the age of the Internet and social media, we have the ability to exchange, sell, or share with others in our community. And we have the ability to foster a new kind of ownership that supports a sustainable future."

One of the challenges with the sharing economy is that communal goods get damaged due to a lack of accountability—indeed, it's a problem with which many furniture sharing and rental services contend. Cognizant of this issue, Judy mocked up norman—a furniture sharing service targeted at career millennials leading nomadic, urban lifestyles. Norman’s furniture items are given catchy names and anthropomorphic qualities. With these endearing personas, users would be less likely to mistreat the furniture.

Members of norman have access to a collection of quality vintage and contemporary furniture offerings. The platform has a friendly guide—fittingly named "Norman"!—who embodies the form of a vintage wood chair and makes helpful suggestions on furniture options based on a user’s profile. Another inviting feature is the conversational user interface (CUI). When members click on the green chat button, Norman “talks” to them. It’s this conversational chatting, and Norman’s witty demeanor, that draws users in.

With each living situation change—whether it is initiated by a new roommate or a new job—there are a multitude of furniture-related details to coordinate. Busy, young urbanites have limited mental bandwidth to manage this, especially if they are looking for sustainable solutions. And unfortunately, many people resort to buying what’s most convenient: inexpensive, disposable furniture.

By making the acquisition and moving process easy, fun, and affordable, norman reverses the role that inertia usually plays in behavioral economics. Human tendencies for inaction frequently lead to missed opportunities or loss. With this service however, that inactivity actually leads to gains: Users can just let norman suggest furniture pieces, and handle the details of delivery and pickup. Members gain the benefit of convenience while also contributing to more sustainable practices.

It is with optimism that Judy looks forward to leveraging her power as a designer to script better behaviors around consumption and waste. Designing through several lenses, her thesis work has shown her that there are multiple strategies that can be harnessed to create change. Channeling the path of least resistance could perhaps be the most expeditious and impactful method. Embracing the qualities of the very things that are a source of environmental damage—disposable products—might in fact be the key to shifting American society away from a disposable culture, and Judy believes that by instilling designs with the same convenience, low-commitment, and low-cost that disposable products possess, a more sustainable future is indeed possible.

See more of Judy’s work at and judy-chi.com and judyjudynyc.tumblr.com. She can be contacted at judychi52[at]gmail[dot]com.