VAKIT: On the Elasticity and Subjectivity of Time

In Turkish culture, there are two words to describe time: There is zaman, which refers to measured time—demarcated in seconds, minutes, years. And there is vakit, which is used to describe a particular moment. Vakit refers to experienced time. For instance, "Turkish coffee time" is defined not with zaman, but with vakit, beautifully expressed in the proverb, “A cup of Turkish coffee commits one to 40 years of friendship.”

The objective of Adem Önalan’s master’s thesis, Vakit: On the Elasticity and Subjectivity of Time, is to reframe our relationship with time—identifying opportunities that lead people to spend time well—from recontextualizing time, to slowing it down through meaningful, memorable life experiences.

We no longer get to make the decisions about where we spend our time; instead, the world dictates what we pay attention to.

Adem believes our relationship with time has become problematic. The average person spends about five hours a day on their smart phones, where we lose our sense of time when scrolling through bottomless feeds in a constant state of distraction. We no longer get to make the decisions about where we spend our time; instead, the world dictates what we pay attention to. These distractions—caused by consumerism, the media, and technology—take time away from family and community bonds, social responsibilities, our passions, and our hobbies.

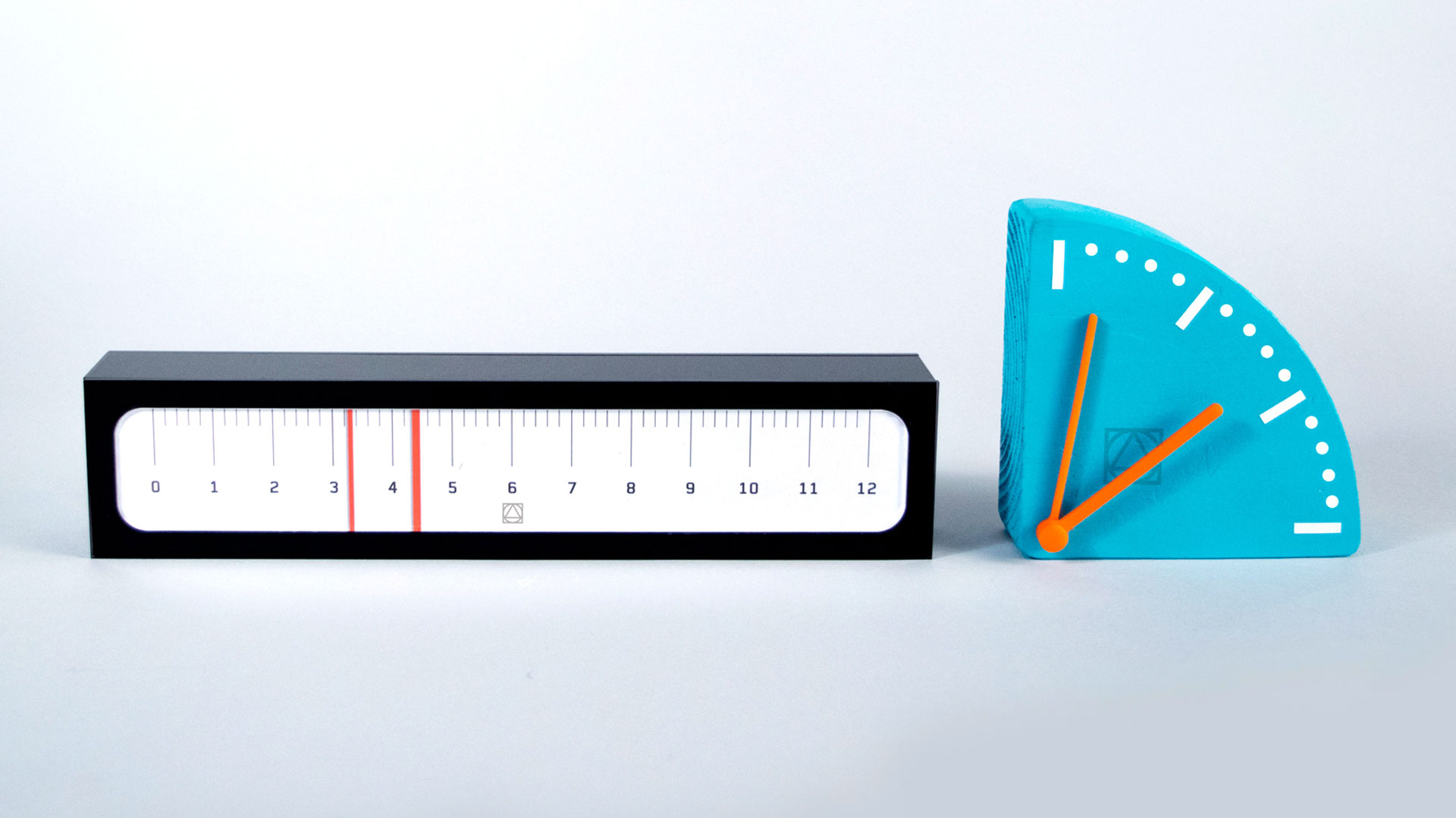

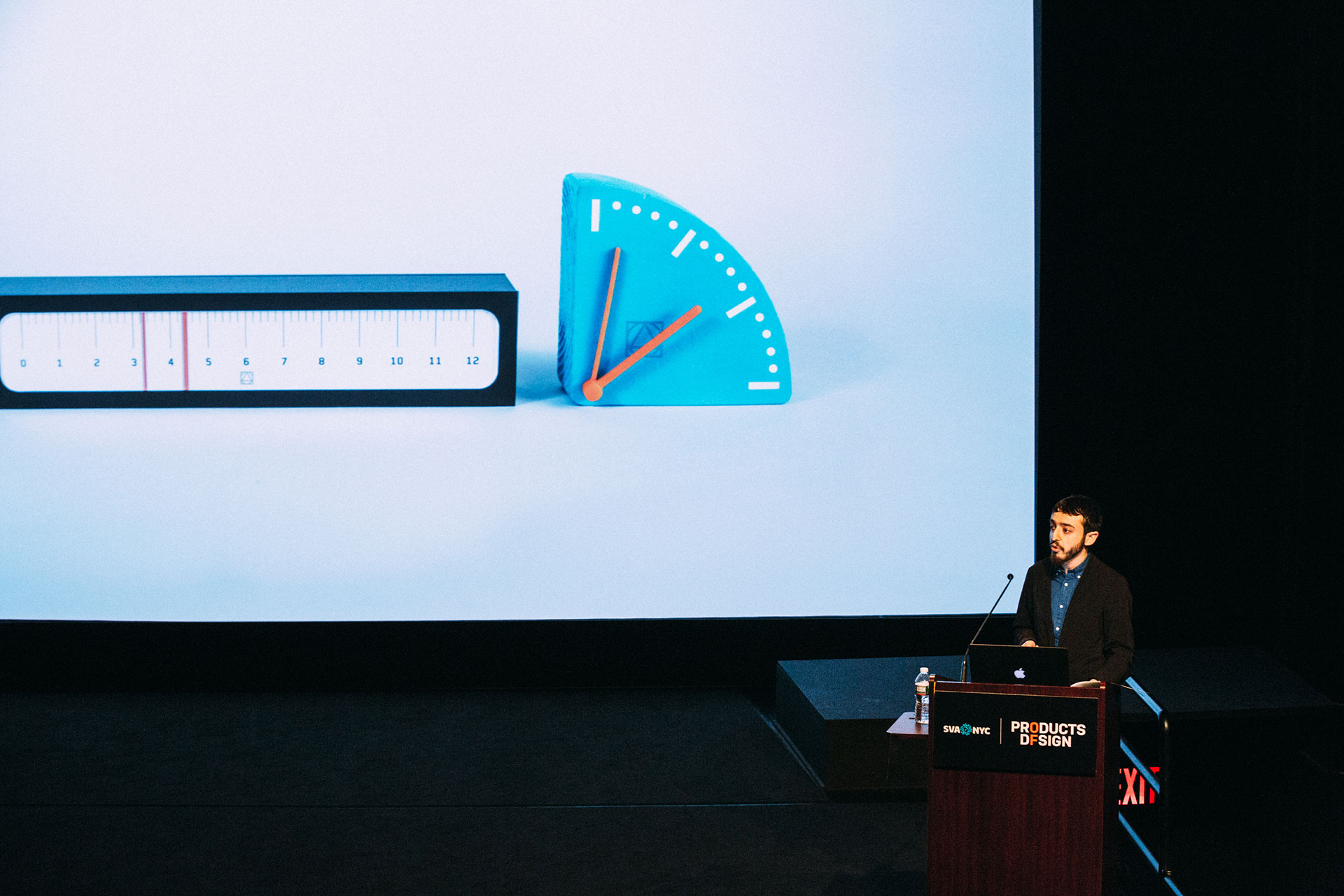

Adem started to search for a better way to experience time. For instance, clock interfaces are continuous, and designed as closed loops, but we live and experience “linear lives”—where time has a beginning and an end as we experience it. Comments Adem, “we start the day when we wake up, and we end the day when we go to bed.” He adds, “The seconds on our digital clocks don’t move until one entire second elapses—as if life were entirely discrete. The numbers on the interface just don’t communicate our lived experiences.”

To address this contradiction, Adem created speculative products that embody the concept of “continuous time.” The first clock is a linear clock that has a clear beginning and end. In the second one, time is dictated in three-hour segments rather than twelve-hour segments. “In these quarter chunks,” Adem offers, “we become more aware of the cyclical nature of time, and how quickly it passes.”

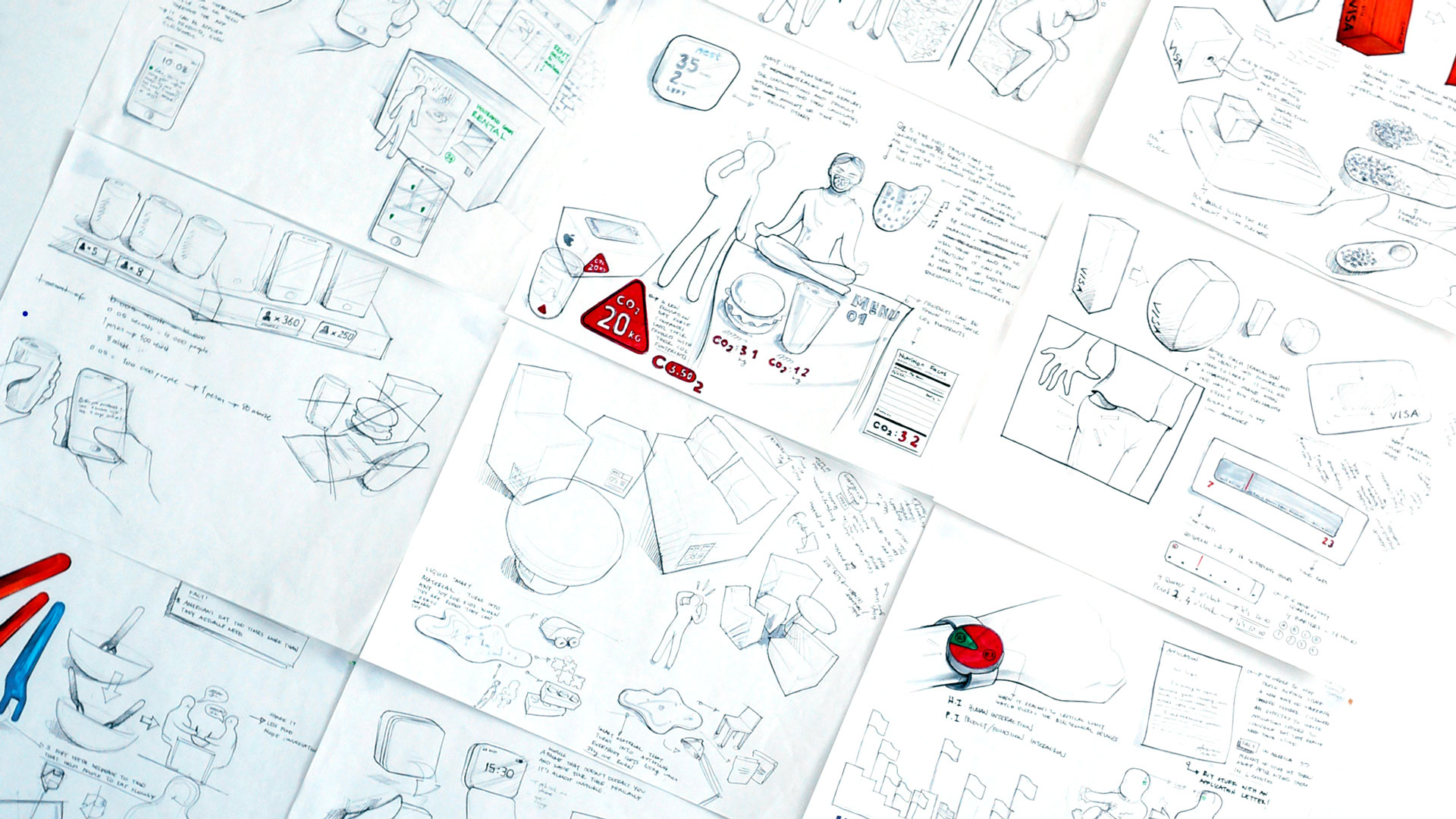

Adem’s research looked at time through the lenses of physics, neuroscience, chrono-biology, and psychology. He read widely—ranging from hard science to fiction, and conducted interviews with over 30 subject matter experts.

In order to observe how people experience time, he organized a workshop where he conducted his “one-second experiment”—testing whether or not people would perceive the duration of one second differently, and how time could warp in different situations.

Here’s how the process worked: On the product shown below, participants were asked to push the button "once per second." The device then calculated how long each person perceived one second to be. (Here, subjects overestimated the amount of time one second was, with an average of 1.82 seconds.) Next, the participants were asked to run around the room for three minutes, after which the experiment was repeated. Each person’s perception of time changed drastically. (Here, participants were much closer to an accurate second, with an average estimate of 0.96 seconds.) This process revealed how our perception of time is subjective, and perhaps more importantly—that it can be altered.

Adem began to wonder: “How can we alter our experiences so that we have a better ‘quality of time,’ and, ultimately, a better quality of life?” To answer that question, Adem divided his body of work into two groups: “First,” he argued, “we need to reframe time. Second, we need to slow it down.”

Adem began to wonder: “How can we alter our experiences so that we have better ‘quality of time,’ and, ultimately, a better quality of life?”

Timeoff Clock

"Although clocks were initially designed for religious purposes," Adem reports, "they later became an important tool of industrialization and modern life. We put them at the highest points of our walls—as if they are infallible." This inspired him to design Timeoff—a clock that only functions when it is needed. When you've got a task to complete, for example, looking at a clock can be counter-productive and even anxiety-inducing. With the Timeoff Clock, you can literally "stop" time so that there's nothing to distract you. When you've completed your task, you simply switch the clock back on, where it will fast forward to the correct time and resume ticking. "There are times that we don’t need to keep track of time, and there are times when keeping track of time even makes us anxious.“ Adem adds, "Sometimes we even live out of time.”

The Timeoff clock is more than a gimmick; it is a way to say “no” to the distractions that constantly fight for our attention. Building up on this work, Adem wanted to experiment with display of time not on our walls, but on our wrists.

Reflect

Reflect is a smartwatch app that changes the relationship between users and their clocks. In the original relationship, the user asks the clock what time it is; in the new relationship, the clock asks the user what time it is.

The user responds by telling the device the time he or she feels. For example, on Sundays, you may want to enjoy your day, and the numbers on the clock may then become meaningless for you. So you would type or say "Sunday"—and that's what the watch will then display to you for the rest of the day! "What if you just want to enjoy the present—do you need a clock at all? When you define your own time,” Adem argues, “it empowers you to spend your time the way you wish.”

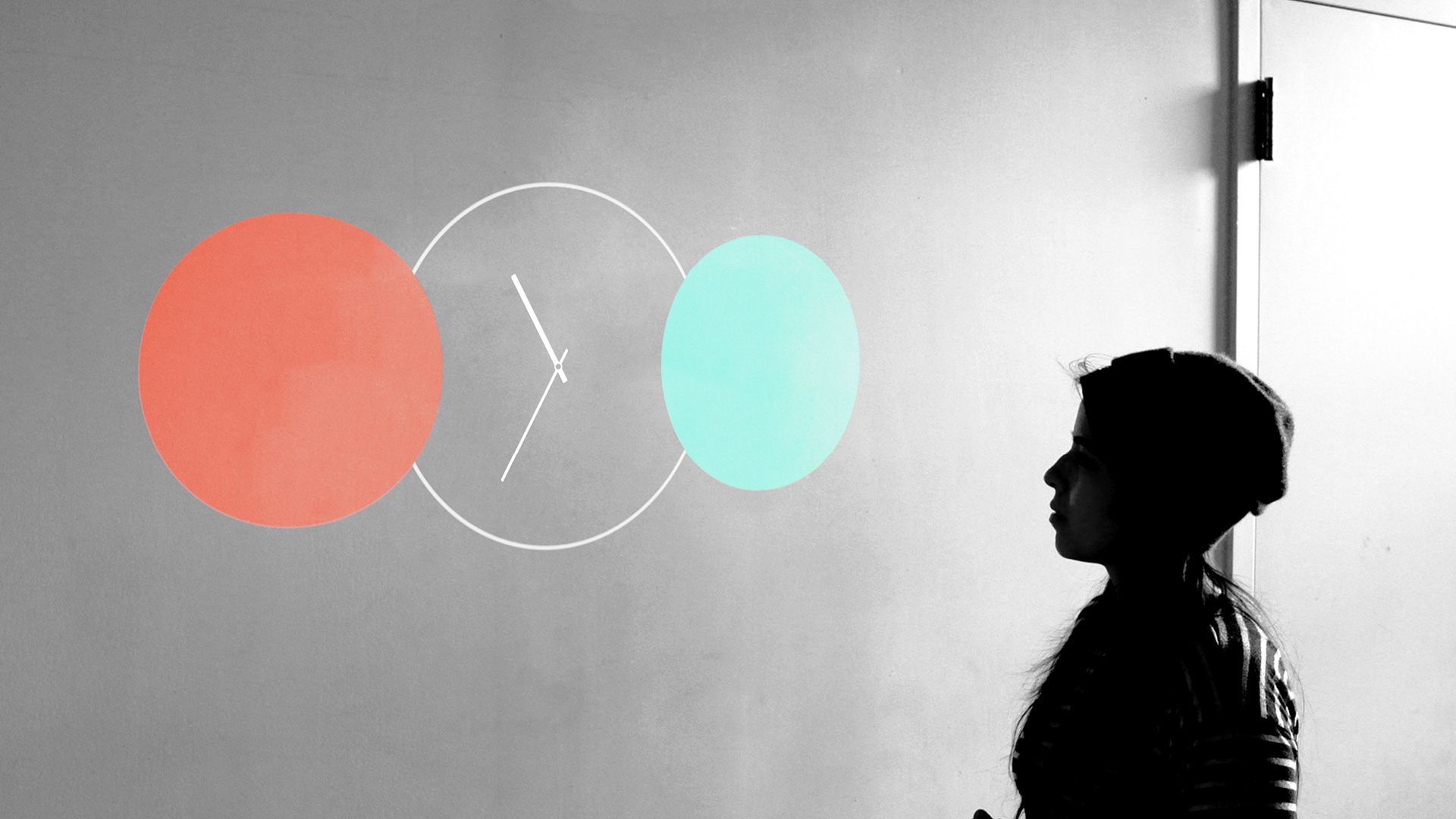

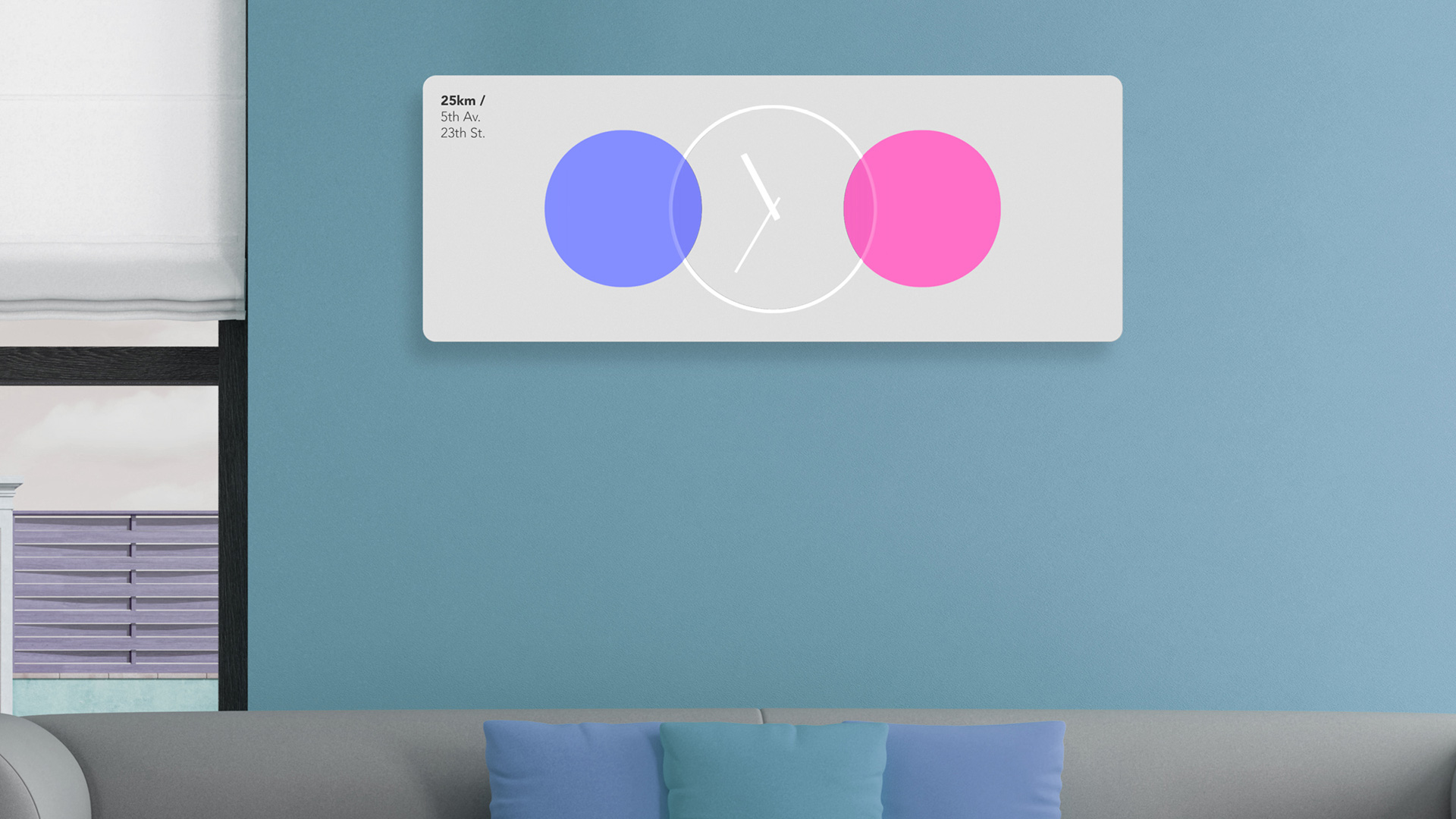

Sync

Time is also valued when it is spent with loved ones. Sync is a platform that functions as a timekeeper—increasing the quantity and quality of time spent together by two people. Sync geo-locates two people in a couple and visualizes their movements through a unique, interactive clock face. Each person has a specific color for his or her individual clock display, and couples can anticipate when they will be next be together. When they get closer to each other, their individual clocks also get closer to each other. The two clocks only become a "single clock" when the individuals fully sync with each other by spending time together. Additionally, through an online dashboard, Sync can also show how much time they spend together each day, week, month, and year.

Neuroscientist David Eagleman advises, “Make sure you stretch your mental landscape by putting yourself in situations where you are learning something new. If you want to slow time down, seek novelty.”

Novo

If the previous projects were about reframing time, the next projects’ aim was to “slow time down." Adem argued that “taking control of our time and recontextualizing it isn’t enough. We have to slow time down, and prioritize meaningful, memorable life experiences.”

Neuroscientist David Eagleman advises, “Make sure you stretch your mental landscape by putting yourself in situations where you are learning something new. If you want to slow time down, seek novelty.” The reason that children experience the passage of time more slowly than adults is because everything is novel to them. The human brain doesn’t process new memories as we age, because things are no longer new to us. We are not able to differentiate last April from last March, for example; often we don’t even remember what happened just three days ago!

Adem envisioned Novo—journal app that encourages and challenges you to bring novelty into your daily life. At the end of each day, it asks you if your day was novel or not. You reflect on your experience in the app, and a beautiful pattern is algorithmically created based on your feedback.

"Your memory attaches this striking pattern to your experience, so when you see it, you recall your extraordinary day,” says Adem. "Novo creates a calendar of extraordinary experiences: You can see where/when you had a novel experience, and where/when you didn't.

“We track the calories we burn, the steps we walk, and the amount of time we sleep. How can we also track the quality of time that we spend?”

Etki

It was at this moment that Adem became very motivated to give people a way to track their daily, remarkable moments. Here, he created Etki—a quantified-self smartwatch that let’s you mark and recall the meaningful moments with creative technology...and a simple gesture. ("Etki" is the Turkish word for 'impressions'.)

Here’s how it works: When a “remarkable” moment happens during your day—perhaps a great lunch with an old friend, or something amazing you saw in the street—you simple lay your hand over the “watch face” to mark it. That’s it; no other gesture is required. When triggered, Etki doesn’t capture any audio, video, or images; rather, it only records the time and location of the event that occurred.

At the end of the day, you can use Etki to remind of of the time and place of your “marked” moments, but you’ll need to use your memory and imagination to recreate them in your mind.

Etki’s purpose is beyond documentation—it is about recalling memories. The device forces you to think about the quality of the time spent in your daily life, “and reminds us that often very remarkable things happen to us...it’s just that we may not notice them,” Adem adds. "As a consequence, Etki motivates you to try to spend your next day more thoughtfully."

Etki can also be paired with an app that aggregates user data, allowing you to compare your days.

But the physicality of the object makes it conspicuous and encourages the body gesture of reaching across with your other hand and cupping its face. Also, having the device accessible on your wrist minimizes the effect of taking you out of the moment. (Pulling your phone out of your pocket to mark the moment would disturb things significantly—indeed, changing that moment.)

“The body of the watch is purposefully concave,” Adem offers, “because the space between your hand and the object is for your memories; it becomes the vessel of your memories.”

Importantly, Etki leverages the special relationship we have with our wrists—especially when we express our emotions. The image below of a child striking a power pose shows how intuitive the behavior of capturing memories can become.

Ultimately, the hope is that the gesture of capturing your moments through Etki will be conditioned; that you’ll instinctively reach across to cup the watch whenever something noticeable, remarkable, or memorable happens. And when the gesture becomes conditioned, the behavior can dissolve organically into the flow of the moment, instead of distracting from it.

“The body of the watch is purposefully concave,” Adem offers, “because the space between your hand and the object is for your memories; it becomes the vessel of your memories.”

Through all of his thesis work, Adem aims to bring forward an ancient perspective of looking at time—vakit—to the way we value and experience time today.

Learn more about Adem Önalan’s work at ademonalan.com, and contact him at ademonalan@hotmail.com.