The Water Token Project: A Cryptocurrency Basic Income Proposal

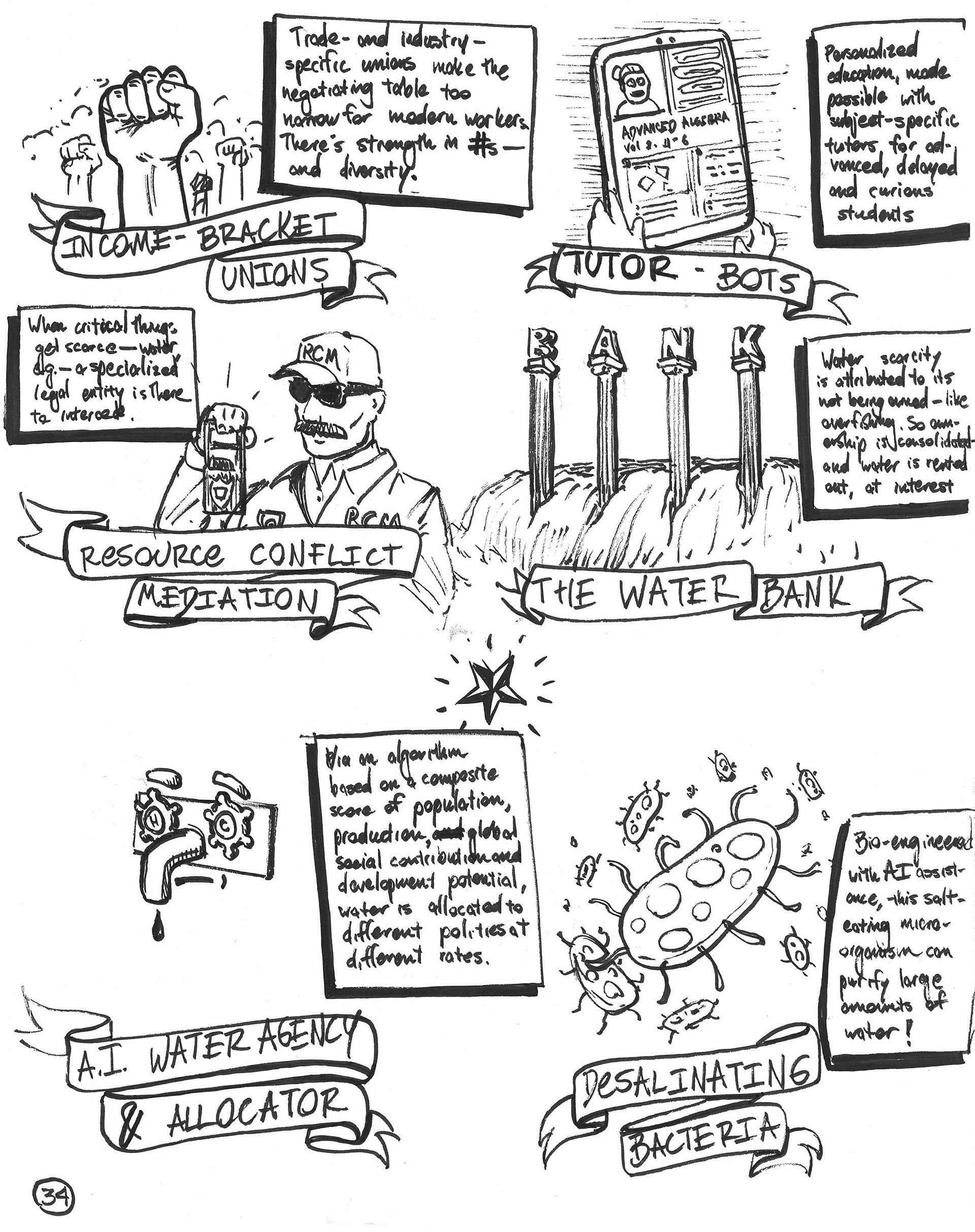

Mockup of Water Bank advertisement by Will Crum

The Water Token Project is a cryptocurrency basic income program designed to create a more equitable distribution of water. Outlined as a policy proposal for the state of California—a notoriously problematic and overextended watershed—the Water Token Project would use an array of machine learning algorithms to constantly recalculate the gallon-value of a water token on a monthly basis and sustainably distribute these tokens to corporations and citizens alike.

In the immediate term, the Water Token Project should increase income for low-income households by enabling them to sell their excess tokens at the water bank and simultaneously increase the costs for excessive domestic water use

Second-year student Will Crum developed the project as part of his thesis, which investigates how breakthroughs in artificial intelligence may impact inequality and social order. “I wanted to explore how machine learning, conscientiously employed, could replace inefficient value systems that favor the biggest pocketbook and short-term impacts,” said Crum. “How can A.I. optimize quality of life for the most people—in the long term?”

Since the 1970s, California’s population has grown at a rate of 1.4% each year, while its water footprint was grown at more than double that rate: 4% each year. The water footprint of the state has long since eclipsed sustainable proportions, currently double that annual flow of the state’s two largest rivers, the Sacramento and San Joaquin. As such, 76% of the state’s water is imported through irrigation and product-embedded water (also known as “virtual water”), leaving the bulk of its agriculture dependent on direct rainwater—a precarious strategy in such an arid state. Additionally, California’s domestic allocation is intrinsically inequitable. Wealthier households use far more water than their low-income counterparts, in part due to their higher consumption of more water-intensive products (like meat).

Wealthier households use far more water than their low-income counterparts, in part due to their higher consumption of more water-intensive products (like meat).

“All signs point to the fact that California’s current water valuation paradigm is inadequate,” Crum explained. “It’s simultaneously disempowering the state’s poorest residents and charting a course for state-wide crisis, as the unpredictable impacts of climate change loom.”

In response, he formed the Water Token Project, a cap-and-trade program for water use in the state of California driven by the value predictions and investment recommendations that advanced A.I. algorithms can provide today.

Each census-verified household is allotted one water token per resident each month. This virtual currency automatically “pays” for the water they use each month. If a household exceeds their water allotment for the month (i.e. “runs out of water tokens before the 31st”), their account automatically buys surplus water tokens from the state’s Water Bank. Conversely, residents who do not use all their tokens each month can sell this surplus via the bank—transforming their unused water as a supplemental income for the household.

The gallon-value of one water token is constantly recalculated by a family of powerful machine learning algorithms, based on a comprehensive array of real-time data sets: meteorological imaging, ground water deposits, economic trends, consumption rates, and more. The token value is designed to create a generous apportionment of water for all private citizens, but can be controlled more strategically in its corporate distribution.

This level of scrutiny was impossible in the pre-A.I. era, but thankfully the Water Bank staff are able to lean on the recommendations of a tiered A.I. network.

The Water Bank determines how many tokens are invested in businesses each month based on multiple factors: industry benchmarks for water-efficient production in that sector; the economic impact of a crop/product on state GDP (measured in dollars-per-gallon); and projected growth potential for that business or industry. This level of scrutiny was impossible in the pre-A.I. era, but thankfully the Water Bank staff are able to lean on the recommendations of a tiered A.I. network that simultaneously evaluates the state economy and climate on a macro level, specializes in different industries and product categories on an intermediate level, and oversees the inputs and potential of businesses on an individual level.

Commercial allocation of tokens is also delivered with best-practice suggestions for water-efficient production in order to meet the Water Bank’s industry benchmarks, which may at first seem stringent to some companies. Additional counseling is available, especially in instances where the bank thinks a company or farm may better serve the state by switching to a different product.

Crum outlined his vision for the project, if implemented: “In the immediate term, the Water Token Project should increase income for low-income households by enabling them to sell their excess tokens at the water bank and simultaneously increase the costs for excessive domestic water use (causing wealthier households to think twice before installing a second pool). In the medium term, the embedded expense of water tokens will increase the cost of high water footprint-products like meat, causing them to be priced like the luxuries they actually are. In the long term, this effect should use market forces to push Californians toward more water-efficient products and services, and guide the state to a sustainable pattern of water consumption.”

The Water Token Project was founded on a research-intensive initial phase, and Crum took great inspiration from the experts he encountered. Chief among them is Arjen Hoekstra, a professor of water management at the University of Twente and founder of the Water Footprint Network, whose work on The Water Footprint Assessment Manual (2011) and Water Footprint Calculator tool were instrumental in building Crum’s foundational understanding of the topic. (The "water footprint" argues that all products have some degree of water embedded in them—but that this is invisible to the end-consumer and typically not reflected in the price. The water token was conceived as a means of making sure that the true cost of water is reflected at every instance and passed along the value chain.)

Additionally, a few other research reports were particularly instructive: Maite Aldaya’s study on Water Footprint and Virtual Water Trade in Spain (2010) and the California Department of Water Resources study Trends and Variation in California’s Water Footprint (2013).

Essentially, all products have some degree of water embedded in them—but this is invisible to the end-consumer and typically not reflected in the price.

Pressed about next steps for the project, Crum concedes that significant groundwork would be required before implementation. “Even before all the data-gathering and engineering-intensive rigor of getting algorithms operational, universal e-citizenship is likely a pre-requisite for effective rollout,” he admits. “How do you ensure that the household-occupant verification process is accurate? How does the program account for undocumented immigrants, the homeless, or residents of substandard housing? All these questions need to be answered if the water token is actually going to reduce inequality, not heighten it.”