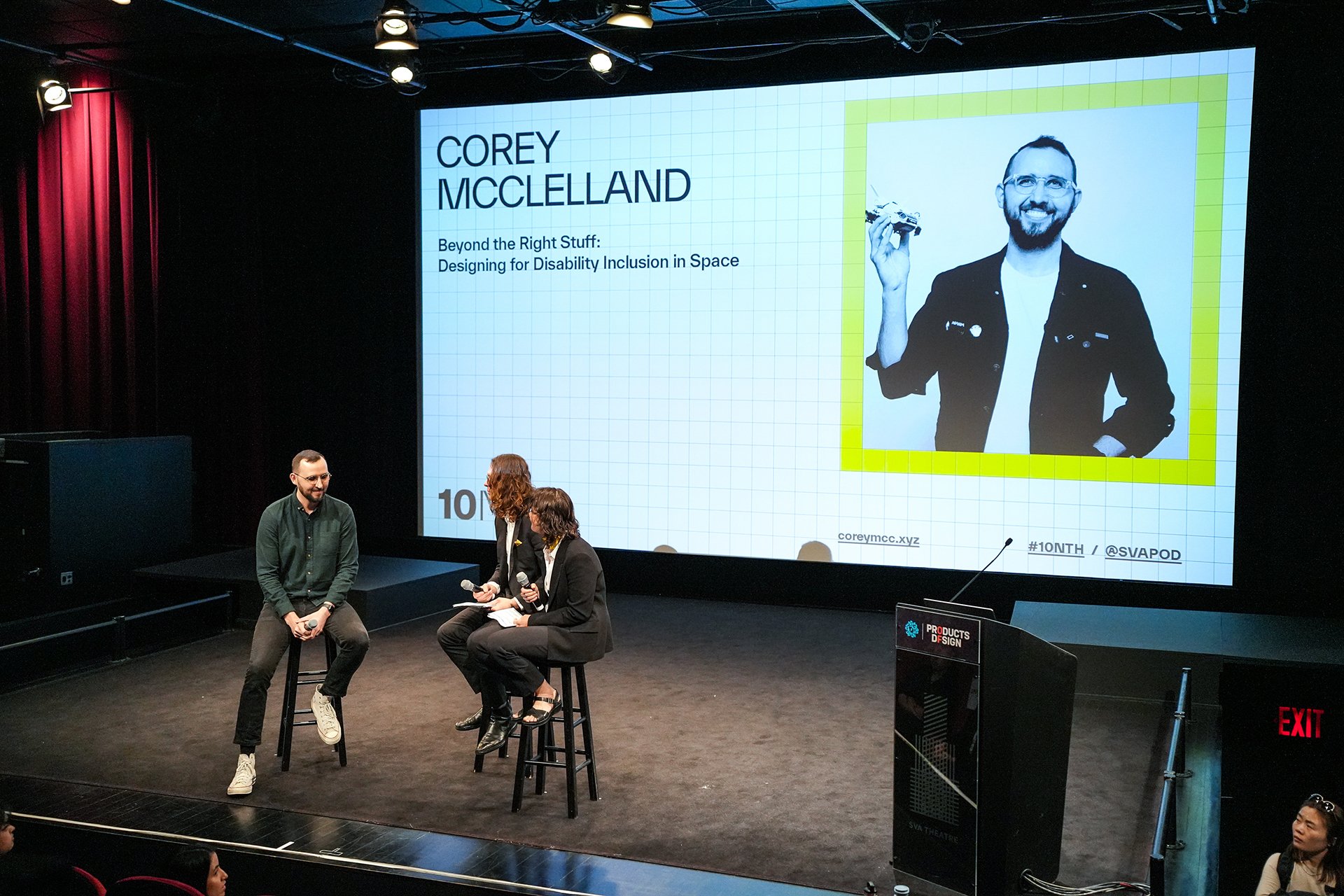

Beyond the Right Stuff: Designing for Disability Inclusion in Space

Corey McClelland's thesis, Beyond the Right Stuff: Designing for Disability Inclusion in Space, centers around researching the challenges and opportunities of designing for disability inclusion in space. One major challenge is the lack of accessibility in space technology and infrastructure, as many tools and equipment used are not designed with the needs of individuals with disabilities in mind. Another challenge is the lack of representation of individuals with disabilities in the space industry. However, initiatives like AstroAccess and other disability-inclusive projects have pushed for change and increased industry representation. Corey's research has shown that individuals with disabilities have unique skills and perspectives that can be leveraged to create innovative solutions to space exploration challenges. The push for disability inclusion in space can also lead to a more accessible and inclusive society as a whole.

"Who has access to space?"

The history of "The Right Stuff" goes back to 1959 and initially referred to a narrow definition of qualified candidates for the US human spaceflight program. This was limited to seven white male test pilots. This definition gradually expanded to include Robert H. Lawrence, the first African American selected for the space program in 1967. Wider still, allowing non-military backgrounds in 1972. Women were finally included in the definition in 1978. And more recently, even William Shatner, a 90-year-old actor with advanced arthritis, was allowed to fly in 2021.

Despite these expansions, people with disabilities remain excluded. However, the European Space Agency is starting to challenge this norm by selecting John McFall, a surgeon, athlete, and above-knee amputee, for their space program. This underscores that it is not impossible to send people with disabilities into space but rather a matter of overcoming entrenched biases and perceptions.

Wearable Anchoring

Corey focused on designing anchoring solutions for individuals with mobility disabilities in microgravity environments. Space exploration has traditionally excluded individuals with disabilities. Still, with an increased focus on inclusive and universal design, Corey aims to ensure that everyone has the opportunity to participate in space exploration and research.

Mobility disabilities present unique challenges in microgravity environments, where tasks requiring fine motor skills and precise movements can be challenging to perform. The current anchoring methods used on the International Space Station (ISS) depend on the use of lower limbs and are limited for individuals with low or no muscular control of their feet and legs or who don't have feet or legs at all.

In partnership with Michi Benthaus, a German student with a spinal cord injury, Corey designed a waist harness prototype with two attachment points for greater stability and control placed near the partner's center of mass, making it easier to maintain balance and orientation. This prototype was tested on a parabolic flight with two research partners with spinal cord injuries. The results of this experiment suggest that anchoring devices, like the waist harness prototype, can be an effective solution for individuals with mobility disabilities in microgravity environments.

Touch Path

For Touch Path, Corey collaborated with Dr. Sheri Wells-Jensen, a linguist who is blind. The project aimed to communicate emergency information to astronauts on a space station through tactile iconography, textures, and patterns. The International Space Station (ISS) currently has no braille system and no intentional tactile textures, patterns, or iconography. Adding tactile elements to the design of a new space station would significantly impact safety at a relatively low cost.

The team collaborated with members of the Blind community by hosting a workshop at the New York Public Library to generate ideas. Attendees were given the opportunity to use various tools to sketch, punch, and print their ideas, passing around their creations and discussing the legibility of different patterns and symbols. The team discussed the challenges of relying solely on braille to convey information to the blind population. It explored alternative ways of communicating information through tactile means that would be more accessible to non-braille readers.

The workshop provided a space for collaboration and creativity, allowing individuals from various backgrounds and expertise to come together to generate ideas for the Touch Path project. The handrail design created through their partnership consisted of two distinct parts: the directional pattern and the shorthand. The directional pattern was used to encode information related to navigating or orienting in a station, while the shorthand was designed to convey essential or more detailed information. The project has the potential to revolutionize the design of space stations and increase the safety and accessibility of space, ensuring equal opportunities for all individuals to live and work in space.

MESA: Modular Ergonomic Space Accessories

Following the successful completion of the anchoring experiment with Michi, Corey began to wonder what it would look like if the environment adapted to the individual rather than the individual adapting to the environment. To explore this idea further, Corey partnered with Michi Benthaus, Viktoria Modesta, and Sana Sharma to design a suite of objects that could be used to create a more personalized and ergonomic living and working environment in space.

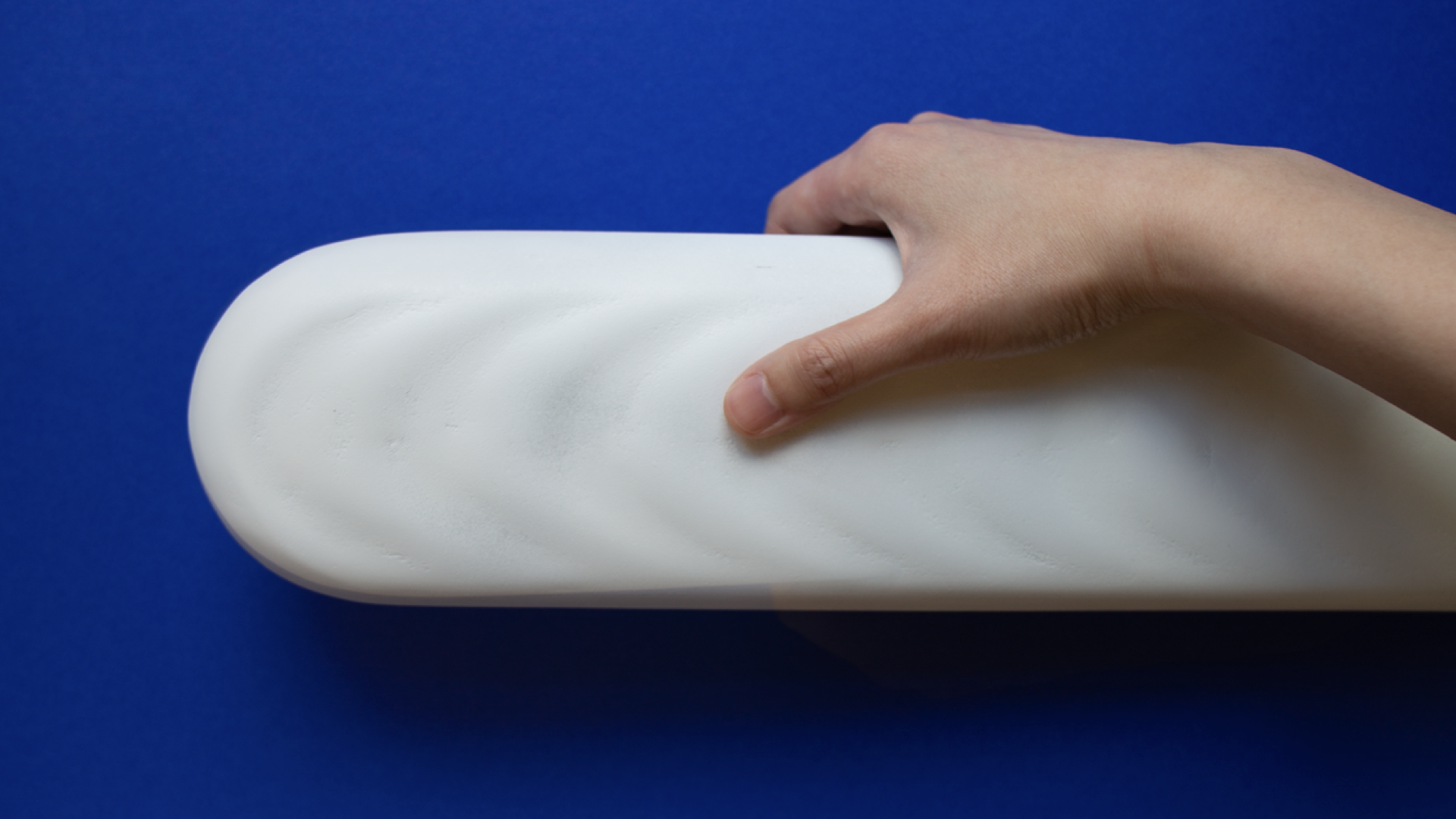

To develop the suite of objects, Corey drew inspiration from traditional furniture typologies, such as chairs, tables, and storage, and imagined what these objects could be without the constraints of gravity. One key design feature that emerged from this exploration was the use of flexible arms. Corey developed early prototypes using foam and gooseneck stands, which were surprisingly strong and comfortable. As the design evolved, Corey incorporated ergonomic pads for long-duration use and various attachments to interface with existing equipment and tools.

The final suite of objects consists of three lengths of arms, which are made of cast foam surrounding a flexible aluminum core. The arms can hold various objects using clips, straps, and magnetic pads and can interface with specialized tracks already being used on the International Space Station. The highly customizable system can be expanded infinitely through 3D printing in 0G. The objects not only enable crew members to work and live more comfortably in space, but they also facilitate social interactions and allow individuals to express their unique personalities in a way that was not possible before.

To learn more about Corey McClelland’s work, take a look at his projects in more detail at coreymcc.xyz.