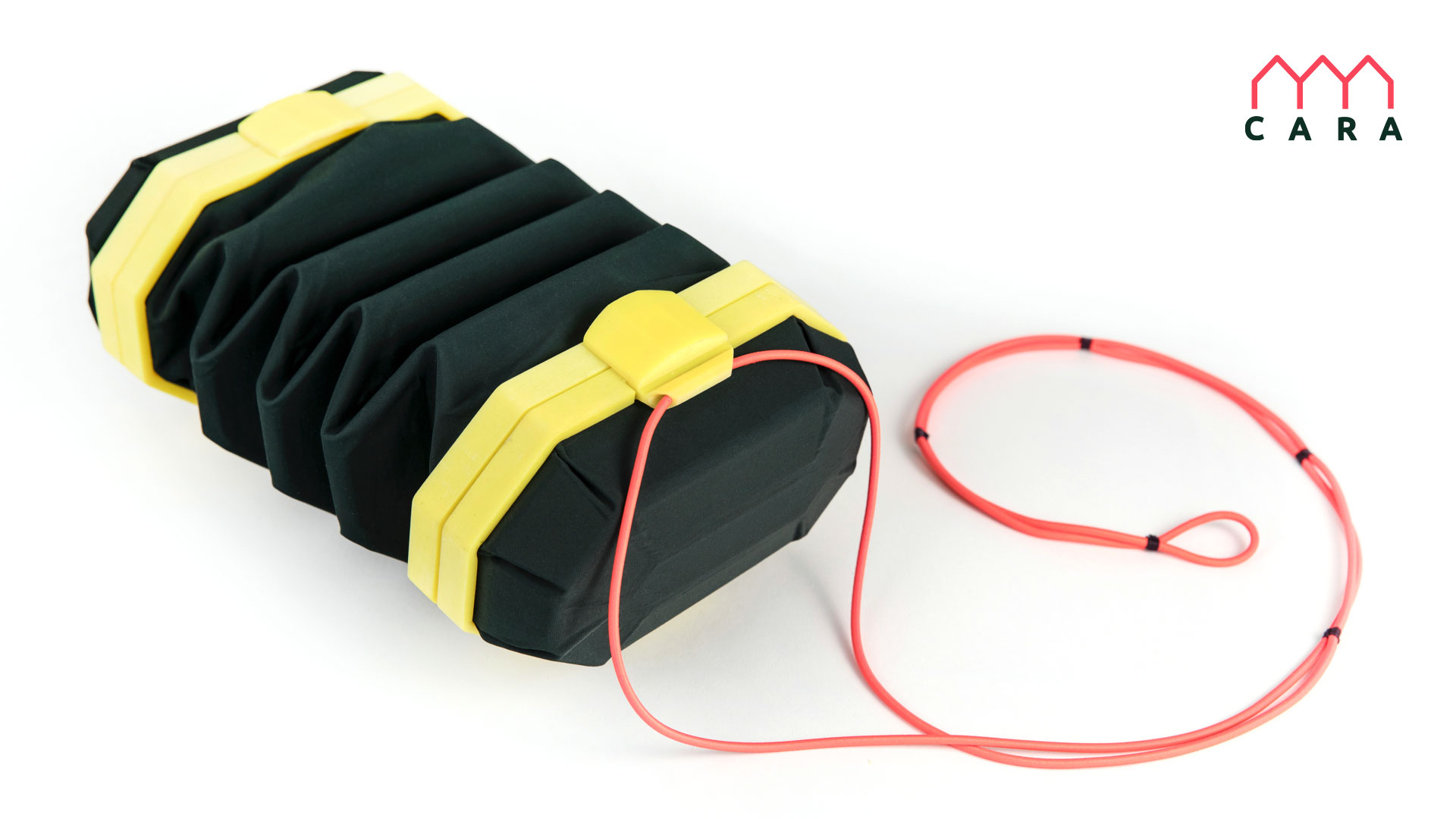

CARA: A Menstrual Product and Waste Carrier for Multi-Day Trips Outdoors

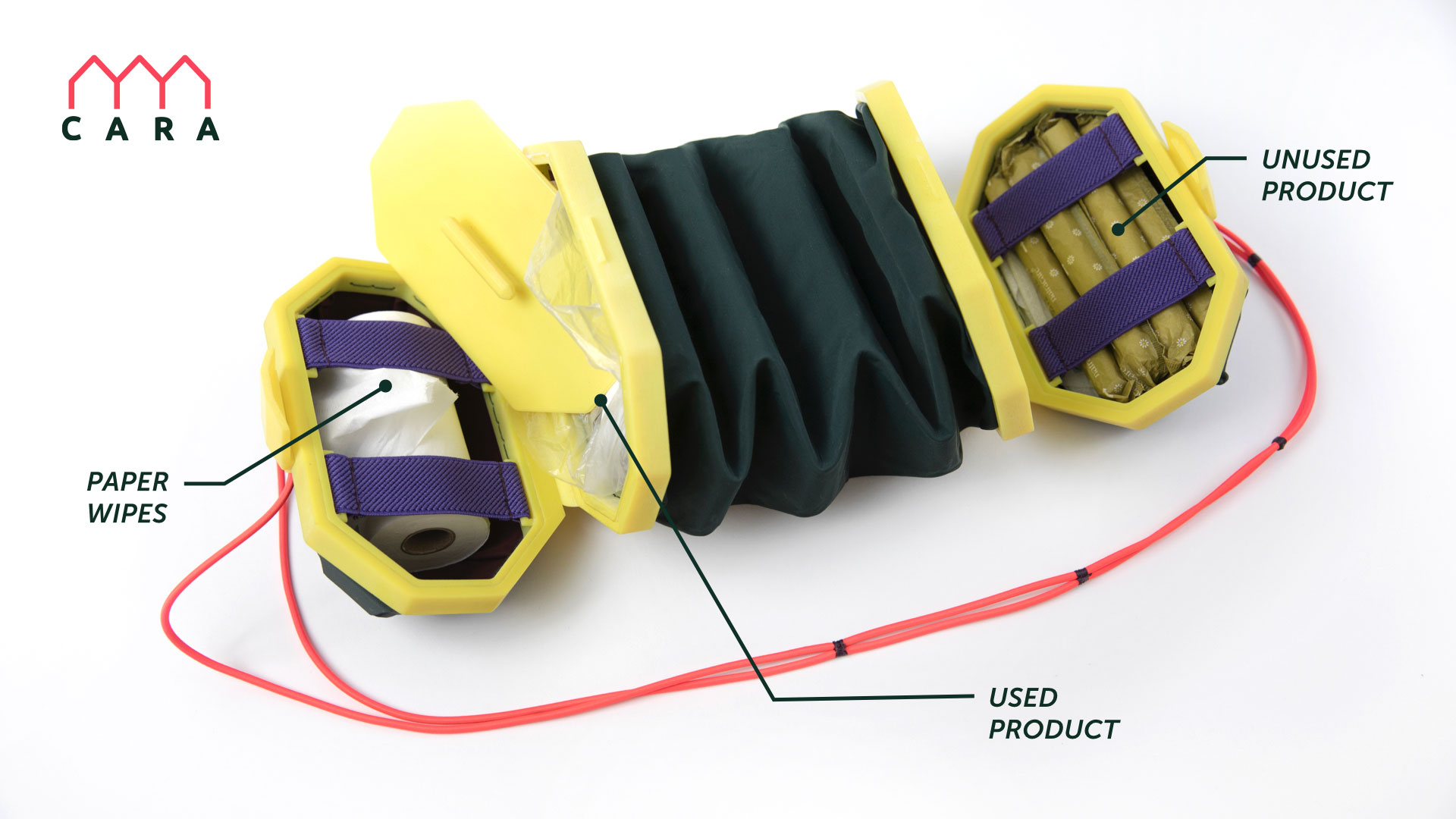

CARA is a menstrual product and waste carrier designed for use in multi-day trips outdoors. Designed by recent grad Alexia Cohen as part of her thesis, DARE + DEFY: A Woman’s Place in the Great Outdoors, CARA—from the word carapace, meaning the shell of a turtle—features an expandable waste collection container at the center, with two separate dry enclosures at the top and bottom to keep unused menstrual products, toilet paper, and/or wipes clean and ready to use.

What makes Cara most effective is that by combining all the "hacks" that women use when of these features in one product, I have effectively eliminated the need to rummage through a backpack for all the elements required every time one has to change a menstrual product, which would be every 3-5 hours. Yet, at the core, Cara honors and solves for a need particular to women engaging in the outdoors and opens up the conversation to stakeholders in the industry. The hacked ziplock bag and canister solutions are great examples of adaptability and resilience that will continue to be effective for women in this sphere. Cara simply questions the fact that we should be limited to this, just because no one in the outdoor industry has cared to invest time and money into considering this type of design for women’s needs. Cara is not only a viable solution to a challenge we face, but an empowering representation that women-specific needs can actually be met through design. Most critically, Cara honors women’s experiences and celebrates our place in the great outdoors. It does so by conspicuously displaying that yes, we menstruate, it is part of being a woman, and we should not let it stop us from doing what we love!

RESEARCH

What do women do now when they have their period while engaging in outdoor activities?

"Early on in my research, I engaged in conversations with several women who were guiding multi-day trips in the outdoors," offers Alexia. "While speaking to Rebecca Stamp, I inquired about the challenges of dealing with menstruation while engaging in these long trips out-of-doors. This was a perfect question for her as she had been guiding trips for teenage co-ed groups at Apogee Adventures in Maine the past summer. It isn’t as daunting as I thought, she argued, because it entails dealing with the waste the same way you would deal with any other waste: you pack it out (including your used toilet paper), following the “Leave No Trace” ethos. Personal waste is collected by members of both genders and they each receive or bring their own ziplock bag, which they cover with duct tape to make it more durable, to hide the contents, and to indicate that it is their personal waste bag. Girls also pack their unused feminine hygiene products in another ziplock bag to keep them dry and protected."

Browsing through the Leave No Trace website, I found waste collection bags, bear canisters, and a small trowel to dig cat holes for human waste, but nothing specific for women’s menstrual needs.

Alexia refers to another source of wisdom in In A Woman's Guide to the Wild: Your Complete Outdoor Handbook by Ruby McConnell, where she writes about the way in which women may hack together a bin using an empty tube of antibacterial wipes, lined with a bag to collect their personal waste. "They may also duct tape a pouch of cleansing wipes to the side of their trash container for convenience," adds Alexia. "They can keep this bin strapped to the side of their pack for easy access. With this system, they need to keep their unused products protected elsewhere." McConnell also encourages the use of a menstrual cup, since it eliminates waste completely, "but this is an option that many women are still not comfortable using," she argues. Alexia comments, "As my classmate and experienced outdoor guide Hannah Rudin expressed, the issue with the menstrual cup in the outdoors is that one’s hands may not necessarily be as clean as they should be to handle this option in a sanitary way; she thinks that tampons with applicators or pads and liners are much safer for outdoor adventure.

"I was curious to get more opinions, and see if anyone had actually designed a product for this purpose, so I went online looking for discussion forums and potential products. Browsing through the Leave No Trace website (www.lnt.org), I found waste collection bags, bear canisters, and a small trowel to dig cat holes for human waste, but nothing specific for women’s menstrual needs.

"I then turned to a facebook group called All Women All Trails: Hiking & Backpacking, an incredible community of over 24,000 women from all over the world who share tips and tricks, favorite spots to hike, and gear reviews. I decided to post a question about periods in the outdoors. In a matter of a mere 48 hours I had received a varied range of about 200 responses from the community. While many advocated for the menstrual cup as well as Thinx menstrual underwear, a lot of them also still used the duct tape/ziplock bag method to store their used tampons and pads. This confirmed the fact that there is indeed an opening to design intentionally for this purpose, as enough women are still using disposable products out of preference and need.

I was surprised to see the bulk of the waste created—since we throw this waste into so many different bathroom bins throughout the cycle, it’s hard to have an overview—and I had definitely underestimated the amount of storage space required.

Works-like Prototyping and Testing

Alexia shares her process in detail here: "To begin my design process, I needed to figure out what size container would be appropriate to hold both the unused as well as the used products. To build my first works-like prototype, I went to the Container Store and bought a few plastic tupperware containers that I estimated could hold both. I then glued the two containers’ bottoms together and created a quick semi-rigid tube in chipboard that I used to cover them and to facilitate adding a handle. Next time my period came, instead of throwing the used products in the trash, I collected them all in the container. I hauled this prototype around between my apartment and school every day, and at the end of my cycle I had a pretty good sense of the special needs to be considered for such a device. I was surprised to see the bulk of the waste created—since we throw this waste into so many different bathroom bins throughout the cycle, it’s hard to have an overview—and I had definitely underestimated the amount of storage space required on that side of the container. This was especially important to note since I had only stored used menstrual products, without including the used toilet paper which I flushed, but which I would have had to collect in the outdoors. The following are the four key conclusions from this first prototype:

Space for waste needs to be bigger, with an option to explore a soft container that might expand as it is used. This would help to keep it a compact object.

Having the unused product lid on the opposite end of the trash lid made use of the product clunky and impractical. Two easy solutions came to mind: have the used and unused product lids facing each other and use a hinged lid mechanism.

The container should have a space to store clean toilet paper and/or wipes.

Some rigidity around the unused products helps to keep them protected and functional.

"Once I arrived at these conclusions, I moved on to creating a prototype including the features outlined above. In looking at ways to hold soft materials on rigid frames, I realized I could use an embroidery hoop-type mechanism to make such a transition. After buying one and testing it with a thin urethane sheet material, I created another prototype. With this new iteration I started exploring ways in which the middle trash section could become collapsible while the ends of the product remained rigid enough to provide some structure to the overall piece, and to provide protection for the unused products.

Final Prototype

"The collapsible mid-section of the second “works-like” prototype was flexible enough to work, but I needed to find a way to make this collapsible feature a bit more apparent and intentional. I began to explore the use of origami patterns that could twist to collapse by using chipboard and tape to emulate hard and soft areas of material, but these proved limiting and dysfunctional. I ended up with a pattern much like an accordion, which provided function and design intention. Once the pattern was set in paper and tape, I pushed on to testing this technique using nylon fabric, a paper pattern cut using a laser cutter, and heat bonding tape. In the first few tries there were challenges in keeping the pieces in place while heat bonding, as well as lining up the seam to bond the flat pattern into a tubular shape. After a few more attempts, I found recommendations online for a better heat bonding material, which allowed for more stable placement of the pieces. I also found that the optimal and most pain-free area to place the seam was along the middle line of the wider pieces in the pattern. With this, I perfected my process and was able to push it onto the final fabric colors with precision.

"While the soft pieces were in development, I was also working on 3D modeling the hard frame with the hinges on Rhino. After 3D printing a few different test shapes, I realized that the shape of the frame needed to speak directly to the accordion pattern in its collapsed form, as this would help with the challenge of connecting the two pieces (hard and soft) both mechanically and visually. Once this was decided, what remained was a matter of deciding upon detailing and small features that would bring this product to the next level.

"The end product features two end caps that hinge and latch onto the main body to contain both the unused feminine hygiene products as well as some toilet paper and wipes. The main body has its own cap to keep the used contents separate from the clean products. Even though the material is waterproof, this section should be lined with a plastic bag for ease in disposal and clean-up.

Read about more of the projects in this thesis at DARE + DEFY: A Woman’s Place in the Great Outdoors.