How India Looks: Localizing Design Tools for a Billion People

For Charvi Shrimali, the inspiration for her thesis, How India Looks: Localizing Design Tools for a Billion People, was a famous proverb that her grandparents would often repeat to explain the diversity of their country. “कोस - कोस पर बदले पानी, चार कोस पर बानी” loosely translates as: “Every few miles, the water changes. Every four miles, the speech." India is a vast country with a population of 1.4 billion and counting. But its varied geographic, linguistic, economic, social, and cultural landscapes means each of these 1.4 billion individuals look, talk, eat, work, and live very differently from each other. This makes India a complex, diverse and complexly diverse country.

“कोस - कोस पर बदले पानी, चार कोस पर बानी” loosely translates as:

“Every few miles, the water changes. Every four miles, the speech."

India’s many distinct and rich regional cultures manifest as a multitude of art, cinema, cuisines, textiles, architecture, linguistics, customs, and practices. "I wish I could share this wealth with you.” Charvi exclaims, “But when I did a quick Google search, all I could find was Curry, Cows, and— of course—the Taj."

The country’s varied geographic, linguistic, economic, social, and cultural landscapes means each of these 1.4 billion individuals look, talk, eat, work, and live very differently from each other. This makes India a complex, diverse and complexly diverse country.

This lack of representation not only shows an incomplete story but also prevents comprehensive, accurate, and compelling storytelling, a tremendous challenge in this day and age, especially for visual designers in India. "Design–that is local, specific, and targeted—is vital in a rapidly growing world," explains Charvi. But designers in India find themselves severely ill-equipped with their current arsenal of design tools. These tools fail to respond to the needs, sensibilities, and emotions of a billion-strong audience.

When asked to tell us more about these design tools, Charvi said, "We use the same tools as everyone else. We look at the same type-foundries, the same inspiration platforms, the same image banks, the same software, and the exact same hardware. These are great tools. But the thing is, I need to work a little harder to make them work for me." This realization prompted Charvi to reimagine some of the prevalent visual design tools in India through the lens of localization.

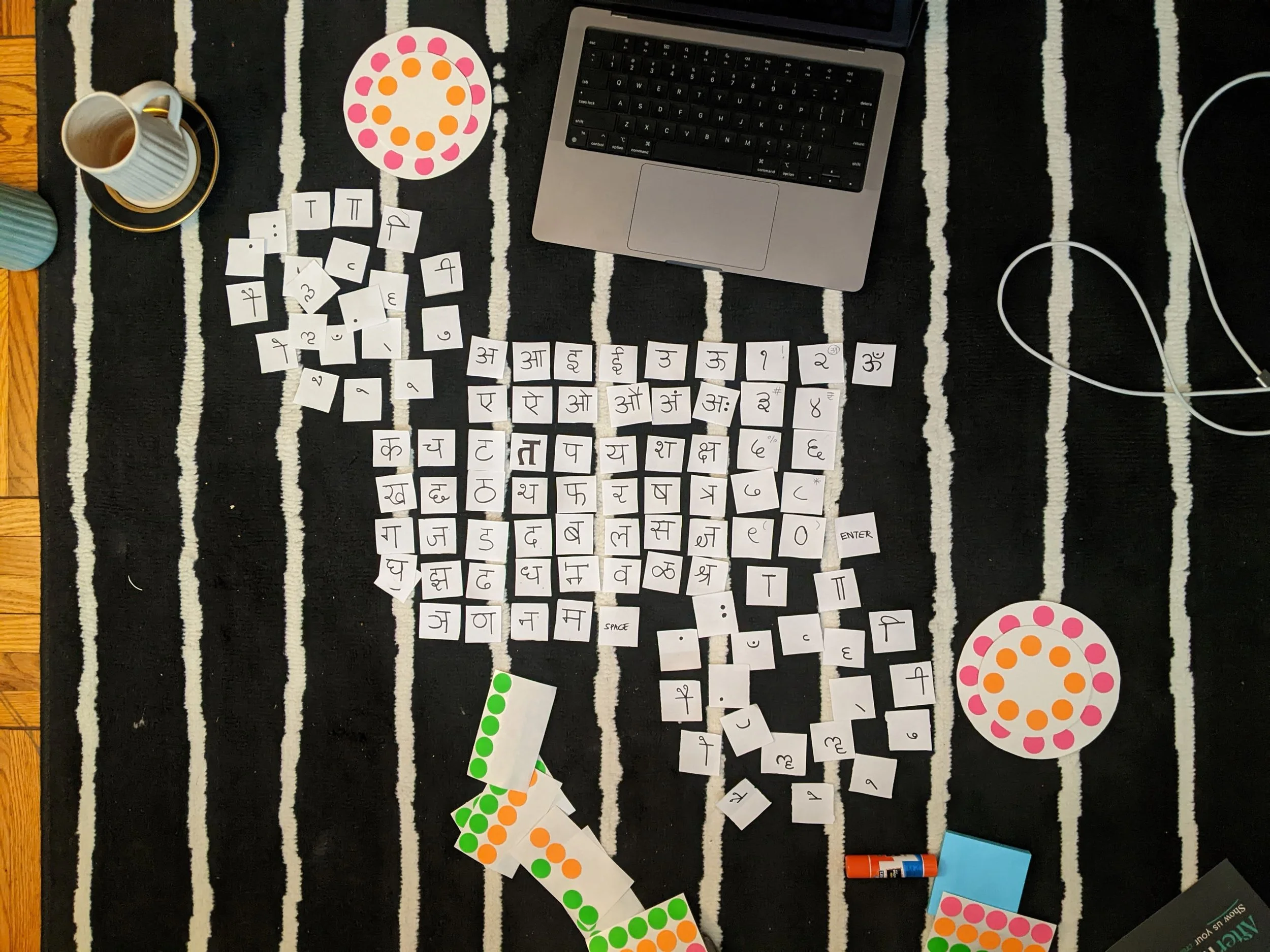

Lipi

India has over 700 languages, each with their own dialects and often with their own unique scripts. Google Font, one of the largest free font libraries in the world, only represents nine of these languages. These nine languages collectively have only 56 font options between them. Compare this to a staggering archive of over 1400 Latin fonts.

"This disparity isn't because there aren't enough speakers,” Charvi explains. “For example, my mother tongue, Hindi, with its many regional variations, is the third most spoken language in the world, with over 700 million speakers. That's twice the population of the US."

The lack of representation can leave a language even as popular as Hindi marginalized.

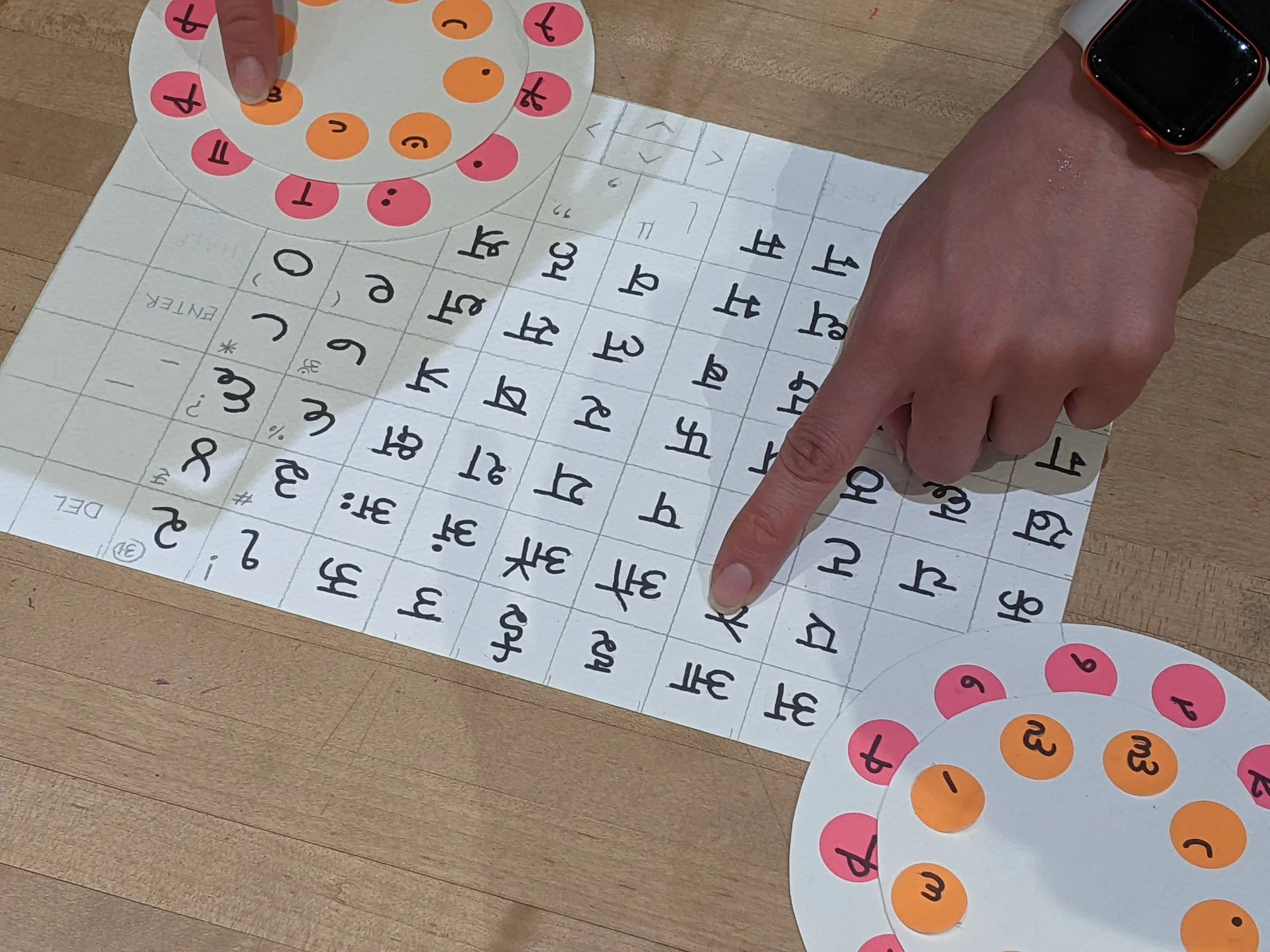

“Even before we start talking about designing a font, typing in Hindi poses a challenge,” Charvi says. A complicated language with an alphabet comprising 52 letters, a system of diacritics, and conjunct consonants, Hindi has been retrofitted into a qwerty keyboard that was designed for a language with half the number of letters.

This forces each key to perform multiple tasks, impeding both the user's intelligence and speed and making them deprioritize designing in any other language but English.

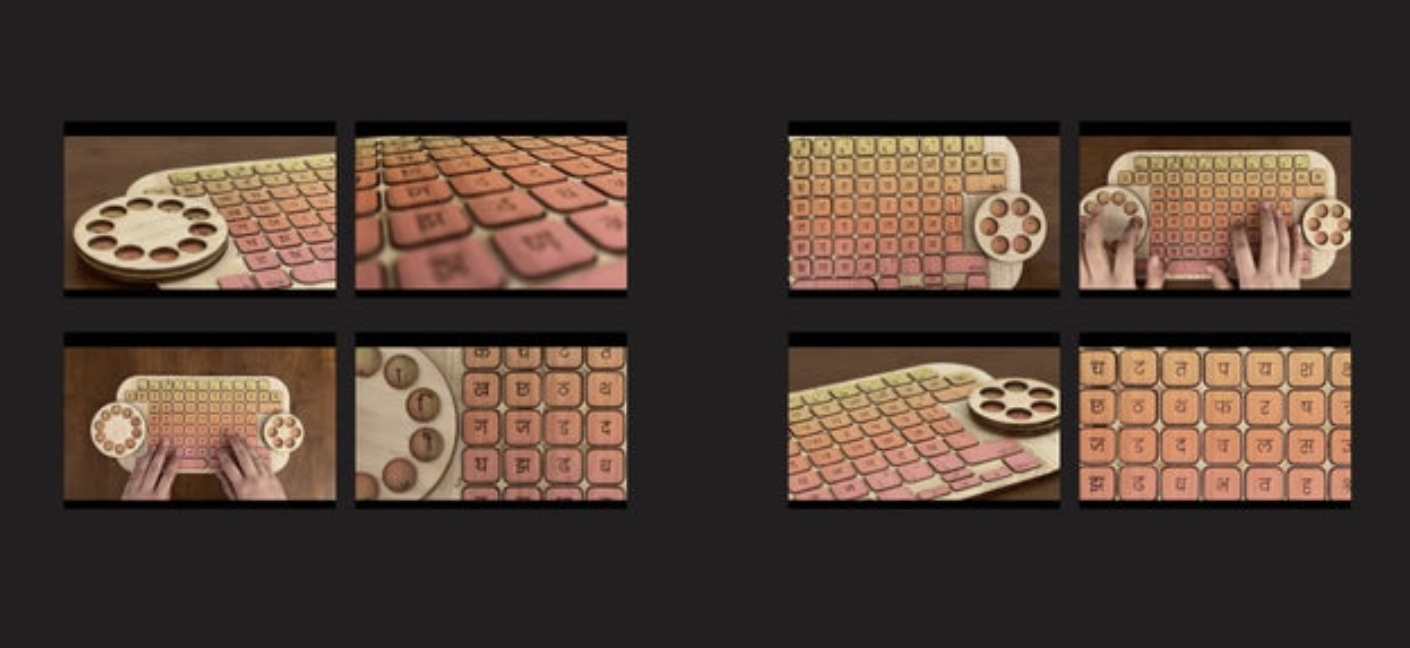

So Charvi wondered, “instead of optimizing design within the existing paradigms, what if we broke away from it?” That's how Lipi was born, a speculative Devanagari keyboard that reimagines the typing experience beyond QWERTY.

Just Having Chai

Interestingly, today visual design is one of India's most rapidly expanding professions, growing at an annual rate of 25%. This surge has resulted from increased demand for digital services, especially since the pandemic, which forced businesses, both big and small, corporate and home-rud, to go digital and begin catering to an audience base of almost 900 million internet users.

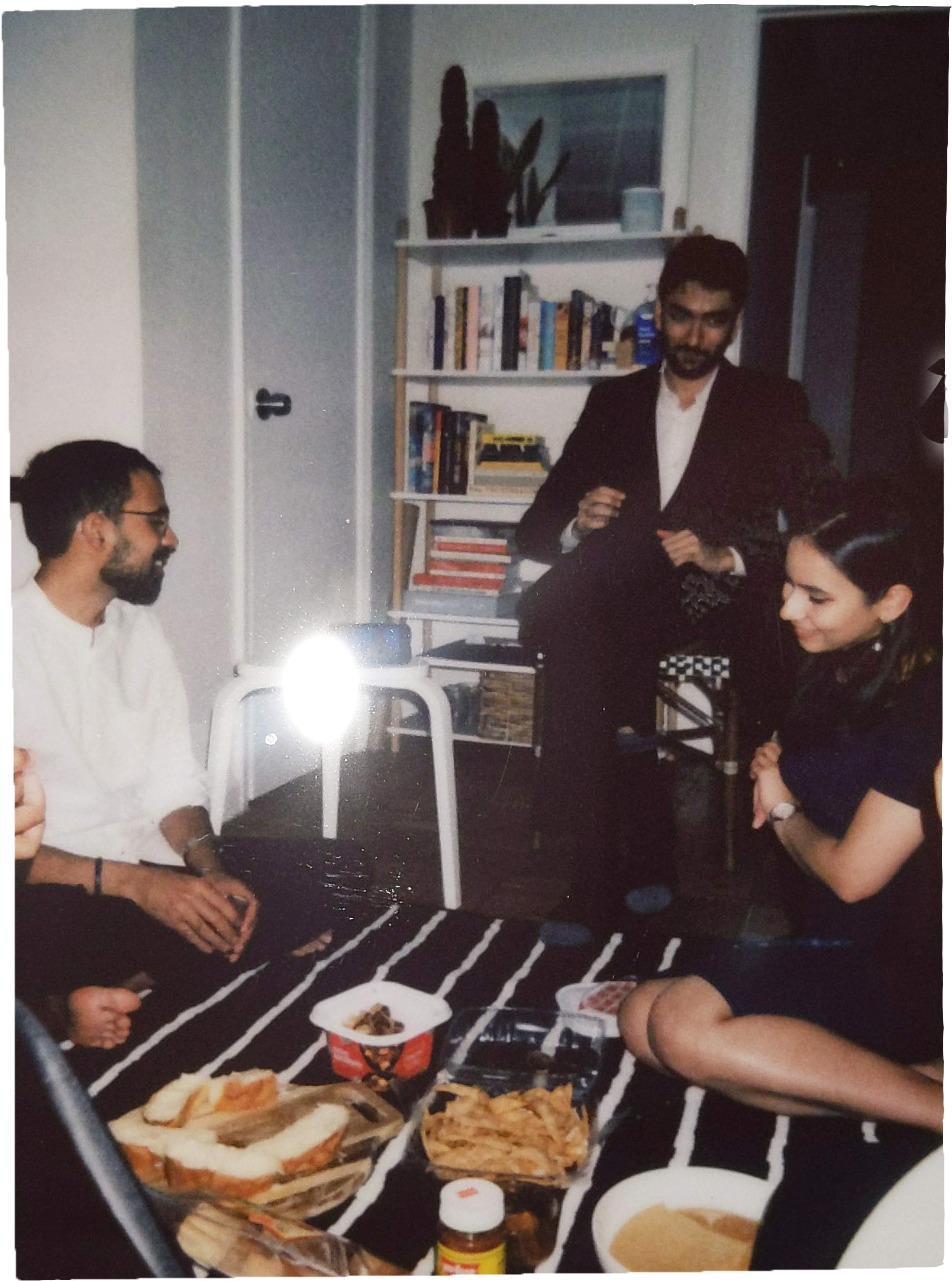

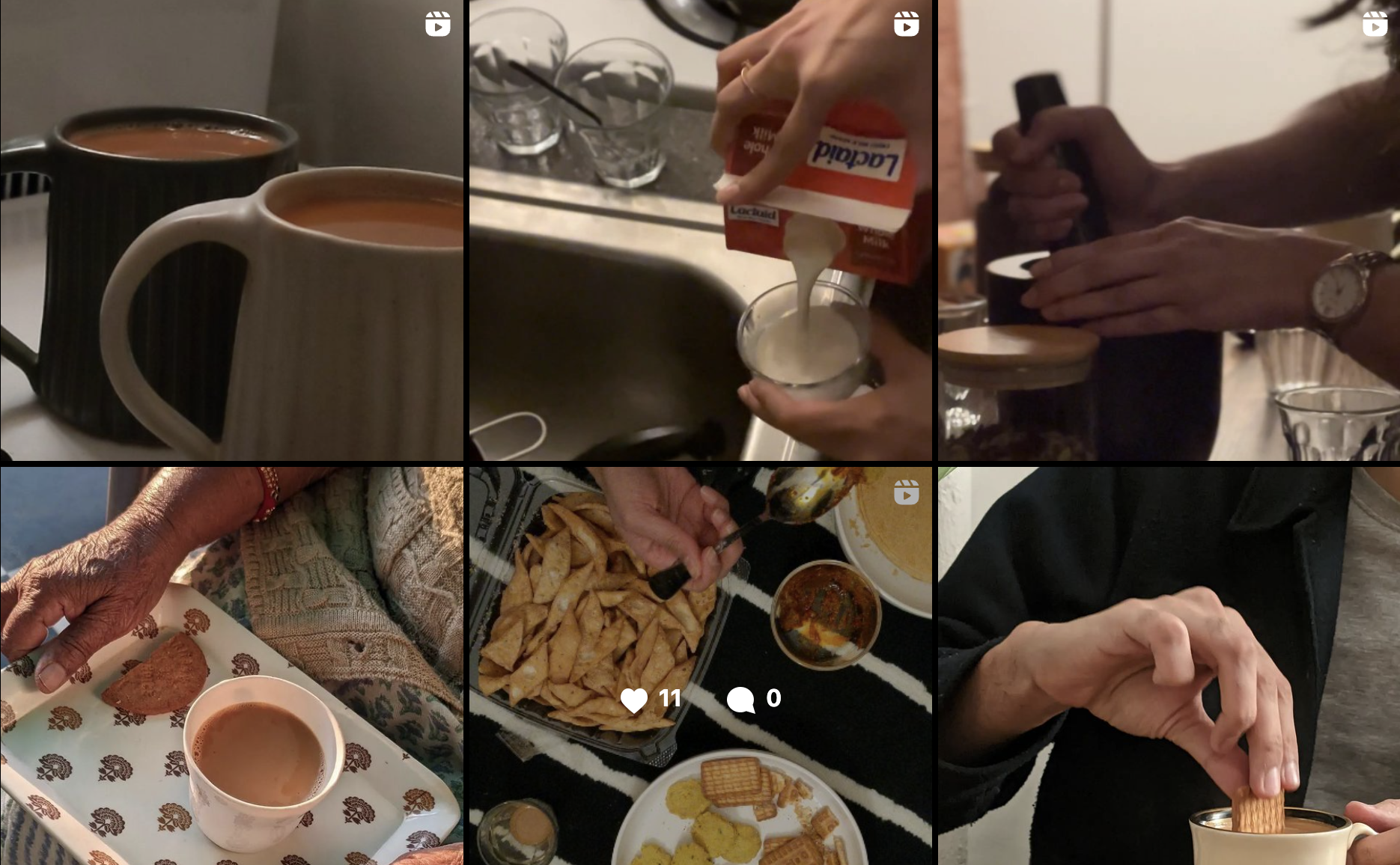

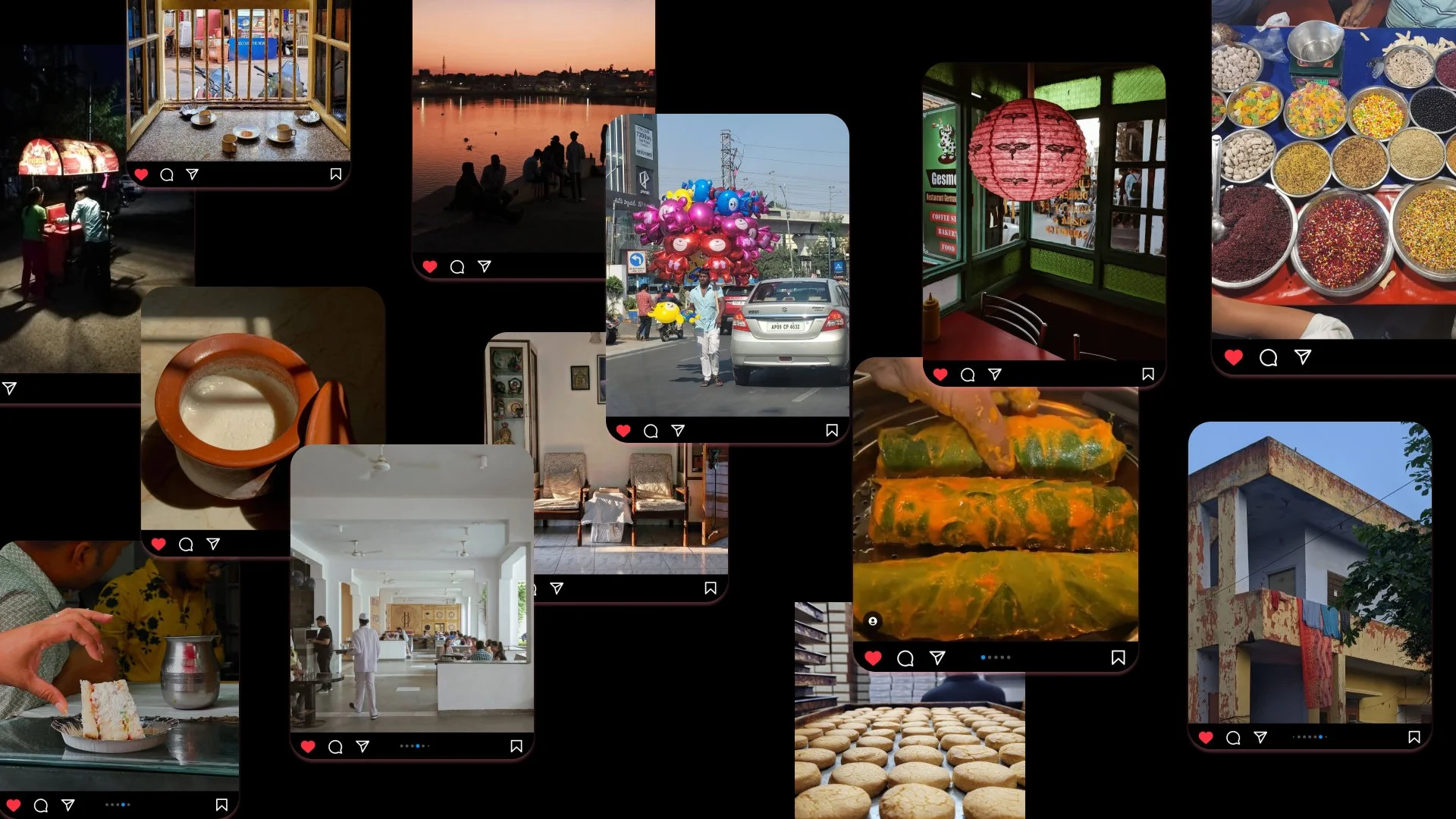

One-third of this current base is also highly active on social media platforms such as Instagram. Since access to the internet has moved beyond the urban nucleus, so has the content on these platforms. Today, Instagram offers an endless directory of everyday lives and cultures across the breadth of the country. This continuous pluralization of content has shown us what is otherwise often left undocumented. This evidence is irresistible, especially when such visual narratives are missing from mainstream media and are continually being erased.

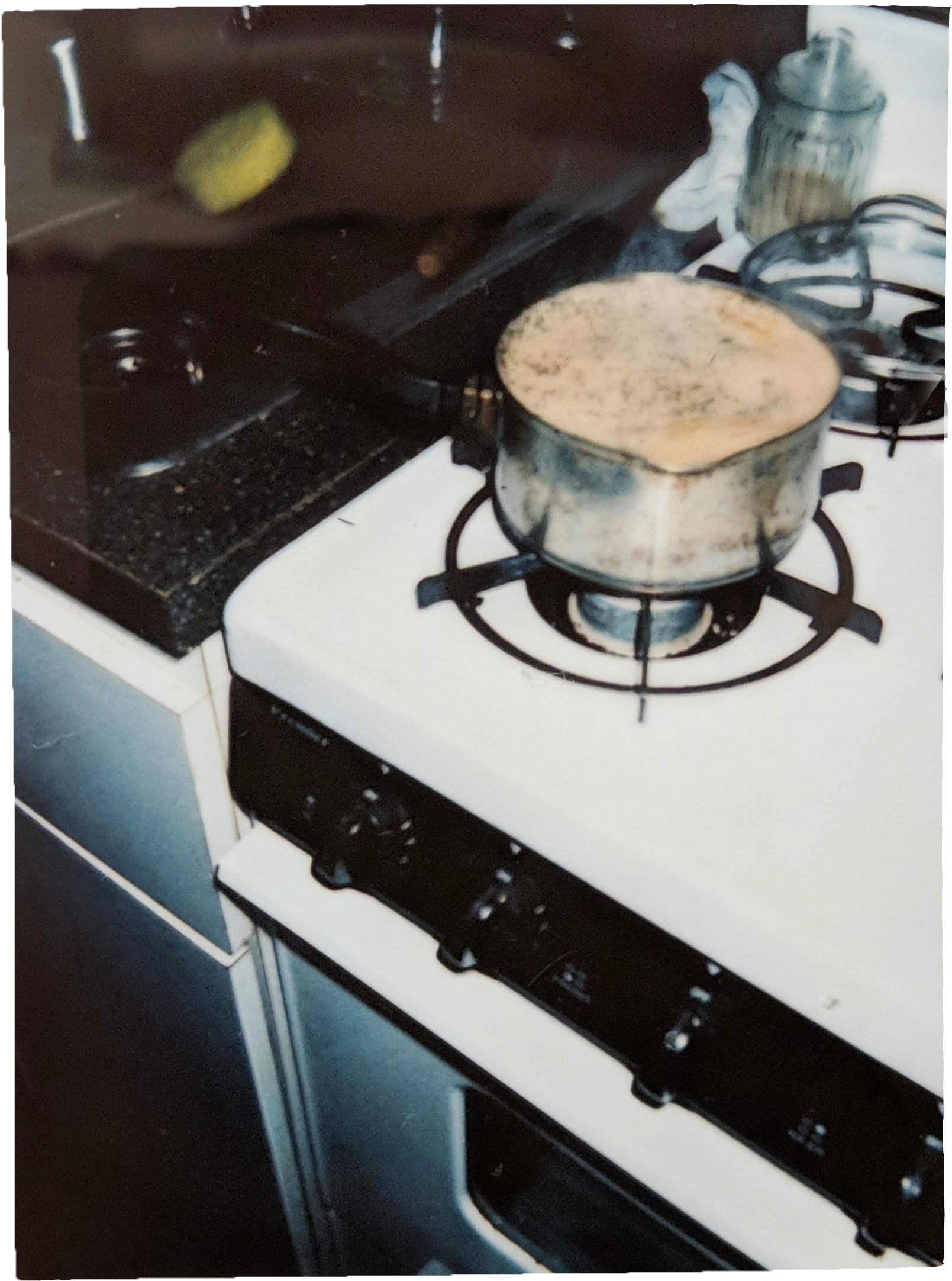

"I decided to participate in this new enfranchisement of documenting the undocumented with an everyday activity that takes up to 90 percent of my parents' day just having chai,” shares Charvi. As Charvi and her friends spent one evening having multiple rounds of chai and capturing every ordinary moment on precious Polaroids, they observed slowing down to document an everyday activity also leads to conversations that otherwise wouldn't take in the absence of this evidence.

Vividh

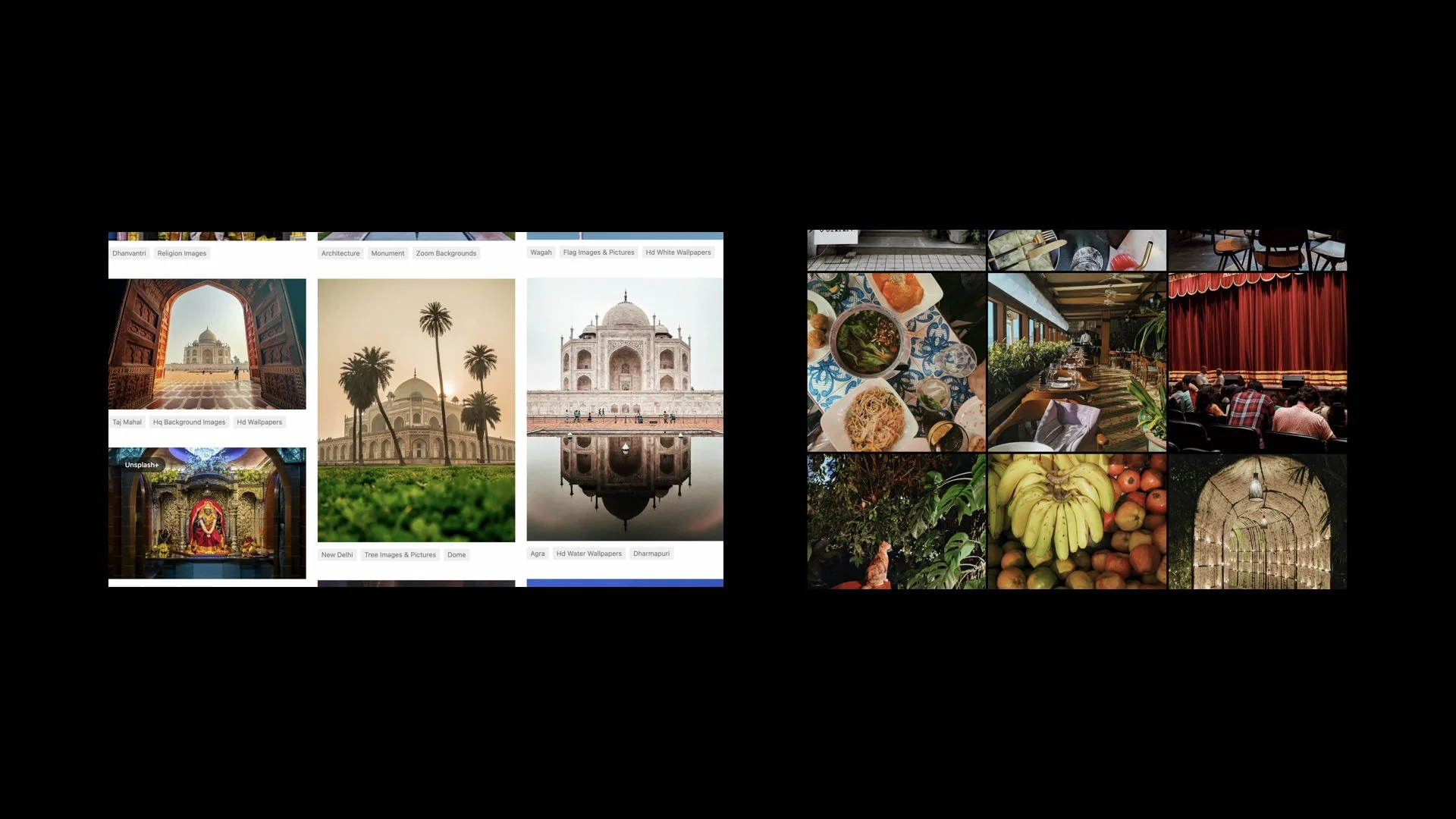

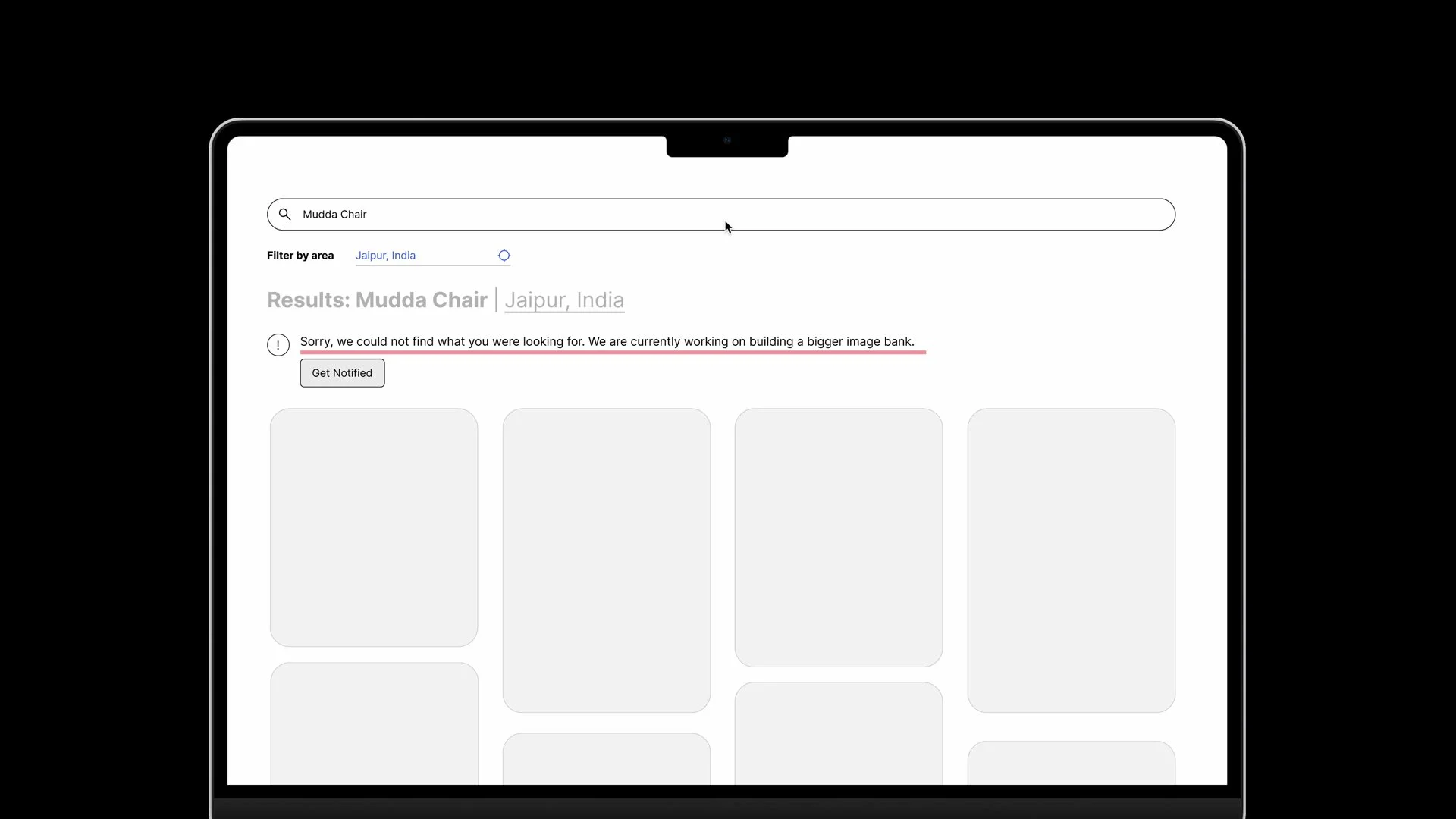

As Charvi shared these images on Instagram, it became more evident why many designers in India use the platform as a visual research tool. Instagram is a visually-forward medium that allows for instant sharing. It provides a storyteller with the agency to tell their own story. This makes for a much richer image bank than popular stock platforms such as Unsplash, which offers limited and unidimensional content from the Indian subcontinent. It made sense why many designers even use Instagram to directly source images from creators. But this is a Jugaad, a makeshift hack instead of a precise solution.

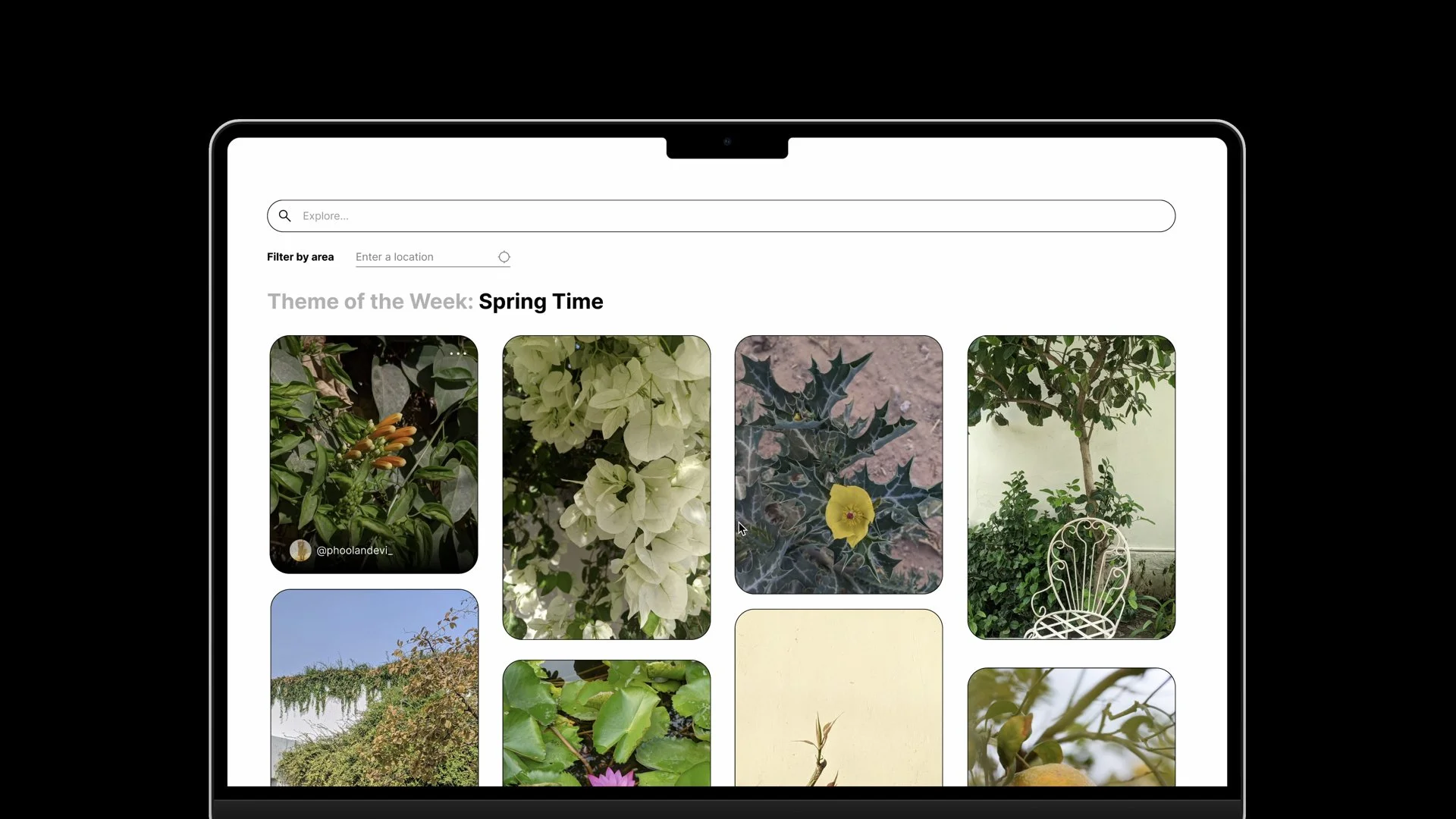

Instagram is not an easily searchable platform. It is ruled by an ever-changing, often unresponsive, algorithm that makes it easy to drown in a sea of content. You need to know the right people to reach the right image. Most importantly, Instagram isn't designed to be a design tool.

Most importantly, Instagram isn't designed to be a design tool.

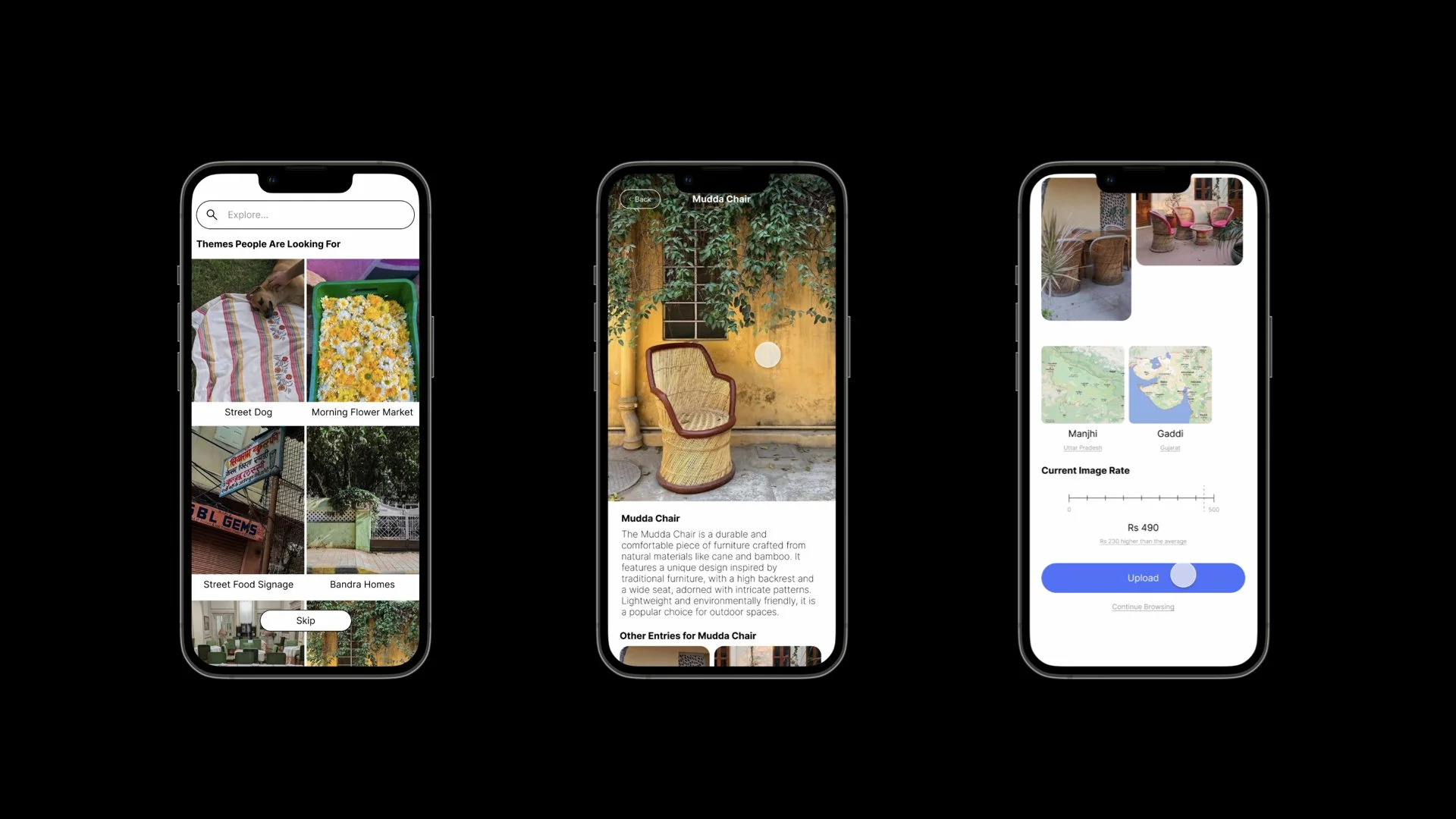

To change that, Charvi created Vividh, a hyper-localized online marketplace for designers, with curated images that capture both everyday and extraordinary life in India, clicked by ordinary users from the country. The platform allows designers to search by location, save and purchase images sourced from Instagram through our broad base of regional content partners.

Location-based search is a critical intervention. Especially in a country where the same image can be interpreted differently, the result can vary based on your search term. So localization cannot be an afterthought. Instead of a centralized headquarters, Vividh operates through 6 different regional teams that interpret each entry and help pluralize search term results. Charvi explains, "This is done to ensure that when searching for an image of a sandasi, a type of kitchen tongs, you will also see results for pakkad, idukki and sansi, regional variations of the same tool."

This is a monumental undertaking, and there are still many gaps in representation. Sometimes, despite this localized, responsive, and collaborative model, Vividh might not have the image you need. To bridge that gap, Vividh would take your failed search term results and turn them into incentivized prompts for the growing community of content creators. It operates through a co-op model that is designed for sharing profits with the creators. With the fixed percentage of profits, creators would also receive bonuses for addressing the visual gaps. The aim is to pluralize, localize and optimize responsibly.

The aim is to pluralize, localize and optimize responsibly.

Localize Captcha, Diversify Data

Soon Charvi learned that in our rapidly moving world, more than just a collection will be needed. "Throughout my thesis, many people asked me, why are you talking about collecting images in the age of generating images?"

AI is our latest design tool. Platforms such as Dall-E, Adobe Firefly, and Midjourney are extremely powerful tools that drastically change how we approach image-making. "But just like all the other tools before them, it doesn't work for me as well for me as it does for you."

The speed at which AI is being integrated into our lives makes it tougher for communities with a limited digital footprint to seek authentic and diverse representation.

The speed at which AI is being integrated into our lives makes it more challenging for communities with a limited digital footprint to seek authentic and diverse representation. This lack of representation also produces AI-generated images that propel the same harmful stereotypes. This risks the danger of a single story.

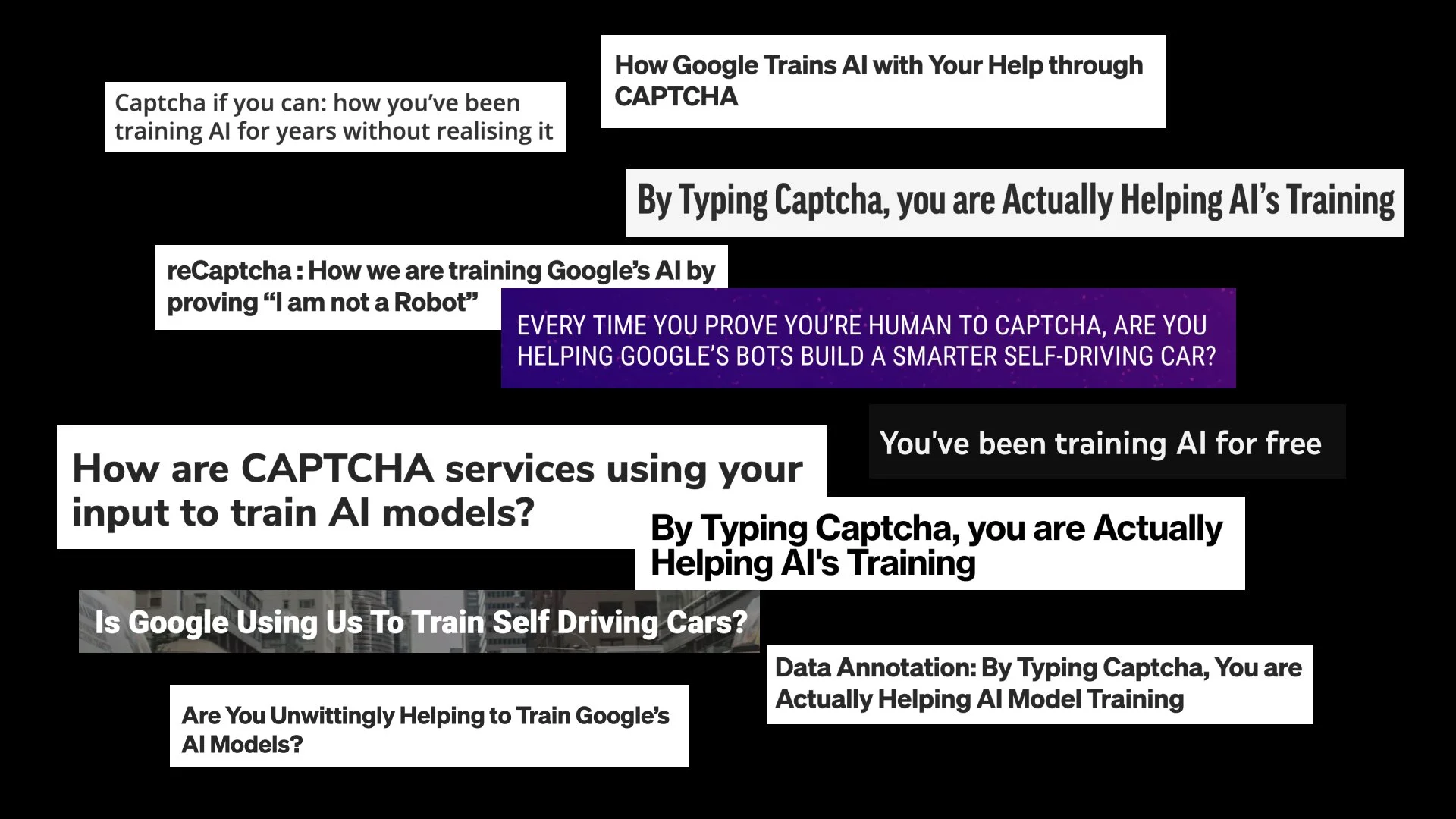

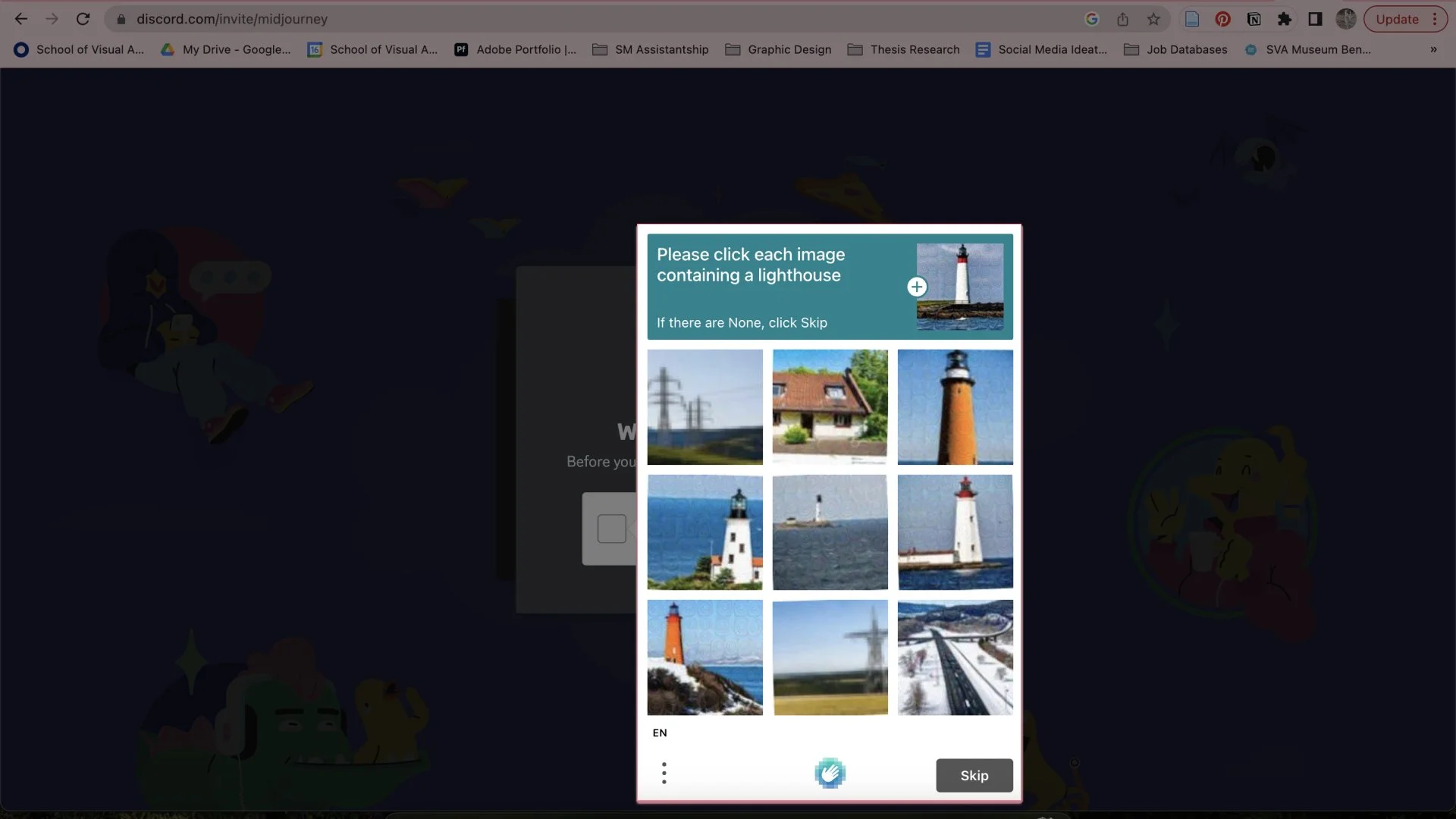

As Charvi dived deeper, she understood that the problem wasn't in the image generators but in the data set fed into these systems. "So I looked at how data was collected to train AI, and the answer was right in front of me. To use these AI tools, I had to prove I was a human. So I did that by picking out every fire hydrant, every crosswalk, and every bus in every single frame."

reCAPTCHA is a free service from Google that helps protect websites and tell bots and humans apart. It's also used to train the same bots. So Charvi came up with a proposal. "If you are going to make me train the bots, let me help you, help it help me." Instead of making everyone identify that one yellow fire hydrant, localize captcha and diversify data. Training the tools of the future, for the future.

"If you are going to make me train the bots, let me help you, help it help me."

Imagine if we could train AI to recognize an Activa on the streets of Jaipur, everyone's favorite ice-cream tricycle, or a hand-drawn kolam on the footpath? What if we could train AI to look at India the way India looks at itself?

End Note

"I am one of a complexly diverse and rapidly growing billion, and this is how I look at India,” shares Charvi.“Imagine the richness when each individual gets to share the plurality of their reality. Because in a country where every few miles the water changes, every four miles the speech, there is no one way to look. We want not only to protect this plurality but also to celebrate it in every possible way.”

All images used in this thesis belong to @phoolandevi_, @rinisinghi, @potatopian_patriot, @nikitabiswal, and @charvishrimali.

To learn more about Charvi Shrimali’s work, take a look at her projects in more detail at charvishrimali.com.